Ukraine’s president Volodymyr Zelensky is in Britain for a surprise visit. “Freedom will win — we know Russia will lose,” he told a joint session of Parliament in Westminster Hall on Wednesday afternoon.

This address is the first he has given in Westminster since a video message in March 2022, when the situation for his country was vastly grimmer than it is now. Last year, when he addressed Members of Parliament, Zelensky had just rejected a British attempt to evacuate him and his family from Ukraine. He was under threat of assassination; and his country’s capital faced siege and — as UK Foreign Office officials still insist — the brand of Russian destruction like that suffered by the Chechnyan capital Grozny and the cradle of Syrian civilization, Aleppo.

Zelensky quoted Winston Churchill and saw parallels in Britain’s wartime defiance of a fascist-ruled continent, and said his country would fight on to the end. When he finished speaking, MPs rose to their feet to applaud, many of them in tears. No doubt this defiance helped many of them to believe in Ukraine’s capacity to resist and to survive, and set the tone for increasingly significant UK promises of capital and arms.

Things are rather different now — even if the response to his speech was equally emotional. The Russian siege of Kyiv has been decisively defeated and much Ukrainian territory has been liberated. Western countries surprised themselves with how significant were the financial weapons they were able to deploy to sanction Russian imperialism.

Many Western countries have provided vital arms and materiel — and training for Ukrainian forces, which are essential to bringing the war to a victorious conclusion.

Yet more is needed. And what the authors of an upcoming book call The Zelensky Effect is something that is keenly felt in this visit.

As a wartime leader, Zelensky rations his foreign visits carefully: so far, he has only visited his country’s greatest brotherly ally, Poland, and its great superpower sponsor, America.

Why the president has begun a flurry of diplomatic visits now is a little unclear. The war is threatening to enter a new phase: a “frozen conflict,” which (without new infusions of arms) might drag on for many years on Russian terms. Perhaps Zelensky believes his former pose of defiance from Kyiv is no longer sufficient to hold allies to their commitments, and the case for more aid can only be best made in person.

There is mild consternation in Brussels that an aspirant EU member like Ukraine would send its president to visit London first — although Zelensky is expected there this week.

But whatever the political fallout from his trip to the capital, Zelensky aims to use these trips to ensure continued support and goodwill from allies and friends, and to have Ukraine’s supporters effectively compete to support his internationally popular cause. It seems to be working. Both the American president and the British prime minister have used Zelensky’s visits to announce an intensification of aid.

Britain will train twice as many Ukrainian troops on Salisbury Plain — 20,000, up from 10,000 per year. The UK has also said that it will begin to train Ukrainian pilots on NATO-standard jets, something they have cried out for since February last year.

It seems the tanks and aircraft which Western officials long said that they could not provide will be heading eastwards, after all. Better late than never.

There is a risk of laboring the point, but Zelensky’s charisma appears to be such — allied to the inarguable justice of his cause — that in person, his fellow leaders are somewhat overcome.

Many worried about Rishi Sunak’s foreign policy. The PM evidently doesn’t think about it very much; he said barely anything about it in two successive Conservative leadership campaigns. If Covid was any parallel, they feared, he might bring in his own experts to trash current UK policy and choke off support as a short-sighted way of, in his own mind, balancing the books. But this has not happened.

Either Sunak is a better man than many, including myself, gave him credit for being; or he is being especially well advised, for example by defense secretary Ben Wallace; or perhaps he has fallen for the charisma of a heroic war-leader of the sort not seen in the West for almost eighty years.

Zelensky is the sort of man even vain politicians cannot help but admire; the kind of man whose example they worry, in their darker moments, they would not be capable of emulating.

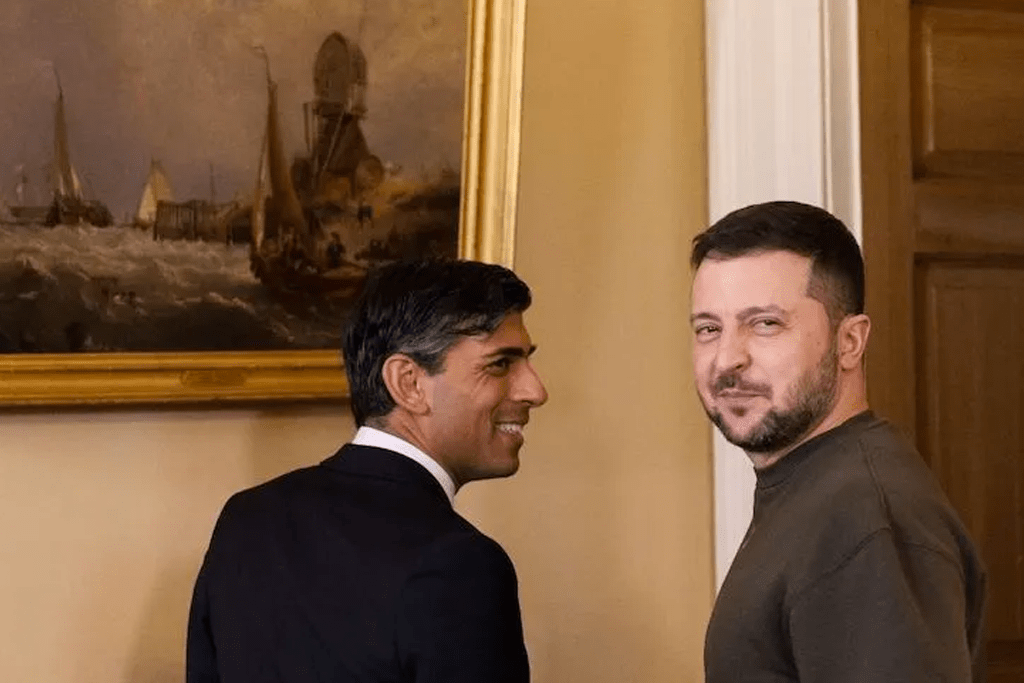

Given how keenly Sunak rushed to Kyiv after his appointment, and how eager he was to be photographed with the Ukrainian president at Stansted Airport on Wednesday morning, I suspect the latter — that he has fallen for Zelensky’s charm — has quite a lot to do with it.

Zelensky’s speech to the US Congress was a real barnstormer. His English is a good deal better than it was in February last year. And despite some confected mock outrage about his attire, the Americans saw the truth in his statement that Ukraine was “alive and kicking” and that American materiel in Ukrainian hands was not charity, but rather an investment in the survival of a free world.

Zelensky touched on similar themes on Wednesday. Britain has long sought a role in defense which its armed forces cannot meet. It suffered reversal in Afghanistan and Iraq, and was a very small part of the global campaign against ISIS.

MoD officials believe that they have found a niche at last: leading the pack on supporting Ukraine — urging the Europeans on, demanding that they be as brave as their claimed honor demands. It’s a noble role and one Rishi Sunak — with prompting from Ukraine’s president — would be well advised to retain.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.