Early on the morning of September 27, 2021, Middlebury College president Laurie Patton had a stone bearing the name of the campus chapel removed from the building. It was done deftly. I don’t imagine she showed up with her own hammer and chisel, but the campus groundsmen executed her orders. Later that day, Patton and the chairman of the board of trustees sent out a message to the community announcing that they had de-named Mead Memorial Chapel, which henceforth would be known simply as Middlebury Chapel. The de-naming was a stealth operation. Outside of a small circle, no one knew it was coming.

Picture a small liberal arts college tucked away in the American hinterland. Picture on the crest of a hill a white marble church with an impressive spire flanked by academic halls. What you have pictured is the Mead Memorial Chapel in Middlebury, Vermont. At least in that visual sense, Middlebury College epitomizes one branch of American higher education — the branch that cultivates a small community of learners deliberately isolated from the distractions and busyness of mainstream society.

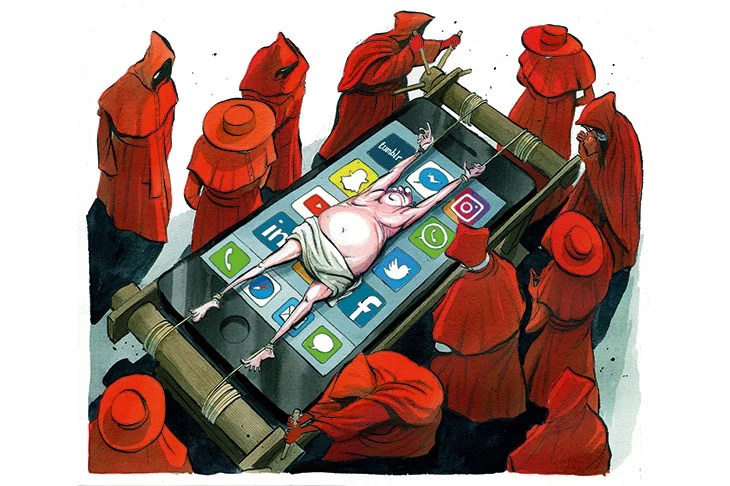

Of course, no college today really sells itself on the glories of standing apart from the hot political issues and social discords of our time. Middlebury College in 2023 is as “woke” as the op-ed page of the New York Times, and it does its best to import whatever social pathologies are vexing metropolitan America. But Mead Chapel could not help signaling something else: a calm dignity and cultural confidence — and a suggestion that the college that surrounds it takes its intellectual responsibilities seriously.

The college, unfortunately, doesn’t always. Back in March 2017, Middlebury drew attention to itself when hundreds of students shouted down a lecture by Charles Murray. Some of the protesters attempted to attack Murray physically and in the scrum injured one of their professors. What caught the attention of many observers was how the college fostered the trouble, did nothing to stop it — and then administered wrist-slaps to the rioters.

The Charles Murray affair has never been forgotten — and while it was the most newsworthy of Middlebury’s departures from respect for intellectual freedom, it was not the last. In 2019, for example, the college attempted to suppress a guest lecture by the conservative Polish philosopher Ryszard Legurto. In 2020, the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE) listed Middlebury as one of America’s “ten worst colleges for free speech.” FIRE’s 2023 ranking of free speech at 203 colleges puts Middlebury as the 189th worst and quotes various disaffected students. One reflected:

I choose to never express my political views, regardless of whether the majority of the student body would agree with them or not. What I’ve found at Middlebury is that the risk greatly outweighs the reward when it comes to expressing my political beliefs.

And another:

This college is an ideological state apparatus meant to program what students think based on the so called morals they preach (generally very politically left). Students are rewarded for parroting the views they hear in class and on campus, like an attaboy.

And yet another:

In a class where we were discussing oppression and privilege, I felt that since I am on the structural oppressor’s side as a white man that I couldn’t share anything contributional to the discussion.

These, of course, are complaints from self-identified conservative students, who are a small minority in FIRE’s reckoning, where there are 6.8 liberal students for every conservative student. And the disaffection of those conservatives has done little or nothing to stunt the public estimate of Middlebury’s worth. The college currently ranks eleventh among “national liberal arts colleges” in the US News & World Report rankings, which can be relied on as a measure of conventional regard if nothing else.

The college, however, has struggled with a handful of faculty who keep inviting the “wrong kind” of guest lecturers or who cross an invisible trip wire by saying something in class that a student or two found “harmful.” Thus a low level culture war has simmered at Middlebury for nearly a decade. I hear about this from friends at the college whom I see fairly often because I have a house an hour away. The view that prevails among these friends is that academic standards for the faculty remain high despite some conspicuous compromises; the students are generally bright but apathetic; and the administration is up to no good.

At the center of this simmer is Dr. Laurie Patton, who is plainly on the side of contemporary progressive ideals. What follows is a story about Mead Memorial Chapel, but it is also a story about President Patton.

Architecturally, Mead Chapel mishmashes the New England meeting house, a Greek Revival colonnade, Georgian windows and a federal spire — but no one cares about such incongruities. This is an American assemblage and the whole thing is striking and beautiful. The spire sits atop an octagonal “lantern” which rests on a four-sided belfry, which rises from a squat bell tower, which lifts off the triangular pediment — a common way of stacking up a New England church. But this one, built of gleaming marble quarried in the Champlain Valley, enjoys a perfect prominence with a lawn that sweeps down to the village.

I had to look up some of the words in that description. “Lanterns” and “belfries” have exact meanings and it is nice to know that each piece of the Mead Chapel assemblage indeed has a name. Names are the center of this story. “Mead Memorial Chapel” was named by Dr. John A. Mead, a physician who served as governor of Vermont from 1910-1912. Mead was a grateful alumnus (class of 1864) and trustee of the college who sought to honor his family by contributing most of the money, $60,000, to build the chapel. It was finished in 1916 and sat unmolested for more than a century as a widely recognized and beloved landmark. It bears emphasis that Mead did not have the structure named after himself, but explicitly as a tribute to his family.

These days this sort of anodyne detail about a largely forgotten historical figure is almost always a prelude to the revelation that the figure in question was an “enslaver,” or at least came by his fortune through commercial ties to slavery, and therefore must be erased to assuage the guilt of today’s more enlightened leaders.

But no. John Mead was just a boy from Vermont who served in the 12th Vermont infantry regiment of the Union Army during the Civil War and saw action at Gettysburg. Later he went to college and then to medical school and had a thriving medical practice for more than twenty years before running for public office. So far as anyone has determined, Mead was untouched by the stain of slavery. Neither he nor his family (pioneer settlers of the Green Mountains) prospered from human bondage.

But the sorts of folks who make it their business to disparage leaders of past generations, even those of modest stature, have other stones to hurl and other poison arrows in their quivers. An independent researcher, Mercedes De Guardiola, found the lethal dart in Governor Mead’s farewell address in 1912, in which the governor “endorsed for the first time a eugenical policy to address a longstanding fear of an increase in ‘degeneracy’ in the state.” De Guardiola published her article, “‘Segregation or Sterilization’: Eugenics in the 1912 Vermont State Legislative Session” in the journal Vermont History in 2019.

Again, one might think this observation would be of small moment. “Eugenics” was once a popular cause among American progressives — and Mead, who was after all a medical man, could be expected to have echoed the prevailing opinion of his time. What Mead actually said on the occasion was brief and uncontroversial. As Tunku Varadarajan summarized it in the Wall Street Journal, “Middlebury’s Scapegoat for Eugenics,” Mead “supported the denial of marriage licenses to syphilitics, rapists and ‘habitual’ alcoholics. He also advocated vasectomies for those with hereditary diseases.” Nineteen years later, the state of Vermont did in fact pass a sterilization law, but it was long after Mead’s death (1920) — and no one seriously thinks Mead had anything to do with it.

Even small colleges, however, must find demons to exorcize — and the busybodies at today’s Middlebury College were ready. This brings us to September 2021, when the college demonstrated its moral rectitude by stripping the Mead name from the chapel “due to his role in the eugenics movement.”

This was done with no public debate or weighing up of contrary perspectives. As I said at the beginning of this account, the action was announced by a “message to the Middlebury community” from President Patton and the chairman of the board of trustees. They explained that the college trustees had followed “a careful and deliberative process,” one that involved “care and deep reflection,” and “awareness” of the “deep personal, spiritual and cultural meaning for generations of Middlebury people.”

The effusive self-congratulations aside, the board members somehow overlooked Middlebury’s own extensive involvement in the eugenics movement. Beginning in 1925, Middlebury made the study of eugenics mandatory for all freshmen as part of its “Orientating Course.” That was five years after Dr. Mead died. The course included a lecture, “What Has Civilization to Expect from Eugenics.” According to old college catalogs, Middlebury had also been teaching eugenics in the 1910s and well into the 1940s, absent any connection to Mead.

The “careful and deliberative process,” and the “care and deep reflection” of the trustees apparently failed to turn up any of this, though a handful of undergraduate students working in the archives managed to discover the facts without a great deal of effort. They published their findings, “The eugenics movement and institutional memory at Middlebury,” in the Middlebury Campus newspaper.

So, as often happens, an activist college president led her board of trustees by the nose into a virtue-signaling briar patch.

A good many Middlebury alumni are not happy. One reached out to me early on, and I soon found myself in conversation with half a dozen; they introduced me to Vermont’s former Republican governor Jim Douglas, who has turned his displeasure about the “de-naming” into an interesting lawsuit.

The immediate news is that a judge has ruled that the lawsuit can proceed, “against Middlebury College officials for their controversial and unannounced decision to improperly remove the name from the historic Mead Memorial Chapel.”

Governor Douglas’s involvement elevates this story in two ways. First, he is acting as a court-appointed administrator of the Mead estate. Members of the Mead family are unhappy about the erasure, and Douglas has advanced the thesis that the college is under a perpetual contract to maintain the Mead name on the chapel as per the conditions of John Mead’s original gift. If the Vermont court agrees, this could have repercussions at many colleges and universities that find ways to rid themselves of names of donors who have passed from the scene.

Douglas’s initiative rings a second bell in that bell tower. It is sure to amplify discontent with the high-handed ways of President Laurie Patton. Like most college presidents who dedicated themselves to advancing “diversity” and leveraging various identitarian discontents, she has her hands full with the US Supreme Court decision in the Harvard and UNC cases. Her immediate response to that was a message to students, faculty and staff saying that the college would abide by the law but “stay true to our mission and commitment to create and maintain an inclusive community with full and equitable participation for all.”

One might think that abiding by the law would include honoring the contract with Dr. Mead, and that a truly inclusive community would take some trouble to include the generations of people who built the college. That long-simmering culture war at Middlebury is growing warmer.

There are some larger lessons in this affair. First, the de-naming of Mead Memorial Chapel is a local instance of the determination of America’s elite to erase our past. It is of a piece with removing historical statues, the imposing the fictions of the “1619 Project” on school curricula, disparaging the Constitution as an instrument of oppression and the myriad other ways that the left now seeks to despoil the country of its pride and self-respect. The cultural vandalism has gone so far that it has become an everyday thing.

Second, canceling the name of the chapel as a gesture towards repudiating “eugenics” is spectacular in its oddness. No one in contemporary America espouses eugenics except fringe figures such as Princeton’s Peter Singer, who believes it is a good idea to extinguish the lives of the disabled. If eugenics has cultural descendants, they are the advocates of easy access to abortion, but their rationale is the freedom of women, not the improvement of the species. Yet Middlebury is not alone in retrospectively canceling figures who once supported eugenics. Rachel Lu reported in the Nation that in 2020 Stanford University “announced that all campus features named for David Starr Jordan would be renamed, as the former university president was a driving force of the eugenics movement.” She also quotes Middlebury professor of gender, sexuality and feminist studies Laurie Essig to the effect that President Patton didn’t go far enough: “eugenics were — and continue to be — central to the way American elites see the world.”

Essig’s comment may be a clue as to what this is all about. Attacking the long-dead eugenics movement is a “woke”-left way to expand on the conceits of systemic racism and America as a pseudo-nation run by a hereditary aristocracy. Anti-eugenicism sees itself not as beating a dead horse but as a noble attack on current day structures of oppression. This is entirely a delusion, but we can now see that it has a delusionary context — its own conspiracy theory in which de-naming Mead Memorial Chapel strikes a blow for social justice against the hidden patriarchy. All this can be done behind the cover of telling the community that the college just wanted to clean up a blemish on its past.

The blemish, however, is on Middlebury’s present as it has veered into an ideological purity campaign that is heedless of history and common sense.