As the war in Afghanistan officially ended on Monday, the world’s thoughts have turned to how the Taliban will govern Afghanistan — and what equipment left behind by coalition forces they now have at their disposal. Some $88 billion was spent by the US government alone since 2002 on security reconstruction — primarily equipping the Afghan army and police forces with training and kit. Now, with the messy withdrawal complete, much of that equipment has been left behind in Afghanistan.

Caution should be taken with that headline figure however. Much of that $88 billion would have gone to the Afghan army in salaries, for instance, while consumables such as fuel and the maintenance of said weapons also ate up budgets too. As defense expert John Pike, director of GlobalSecurity.org, told Politifact, ‘very little’ of the total sum would have been spent on equipment. He estimated that the military equipment remaining is worth less than $10 billion, though virtually all of it could be considered under the category of weapons.

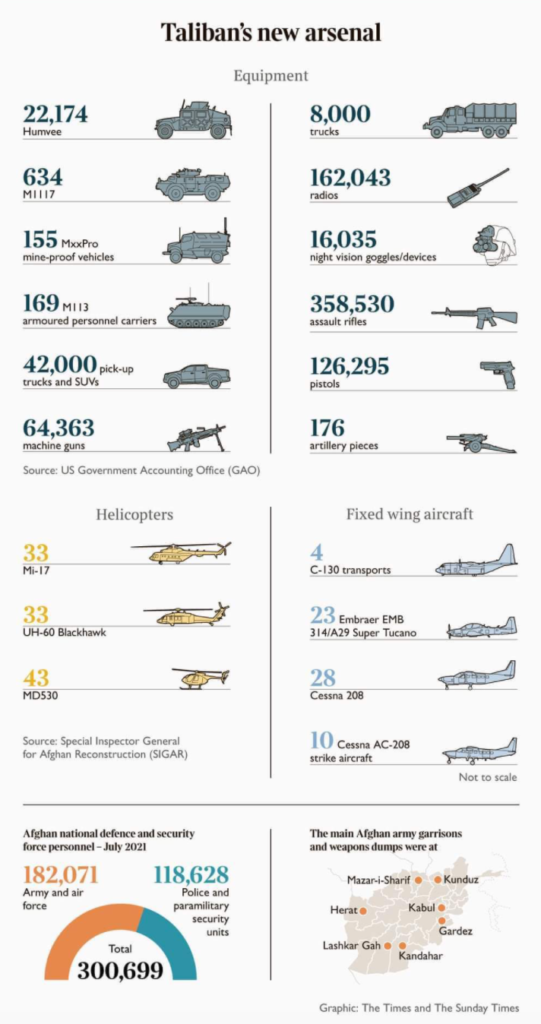

The Sunday Times of London published a graphic which went viral last week, depicting the total amount of equipment (guns, trucks, aircraft and so on) that was sent to Afghanistan during the 20-year occupation. This includes up to 22,174 Humvee vehicles, nearly 1,000 armored vehicles, 64,363 machine guns, and 42,000 pick-up trucks and SUVs. Weaponry includes up to 358,530 assault rifles, 126,295 pistols, and nearly 200 artillery units.

Again though this is a total inventory of weapons sent over two decades: much of that kit will no longer be in the country. Figures for SIGAR, the American mission in Afghanistan, show there were only three C-130s in the country at the end of June. Reports also suggest some ANDSF pilots flew their aircraft to neighboring countries as the Taliban advanced, with the Wall Street Journal reporting 46 aircraft were flown to Tajikistan and Uzbekistan.

Analysts Stijn Mitzer and Joost Oliemans have done an inventory of captured Afghan aircraft of which photographic or videographic evidence is available with 13 aircraft, 38 helicopters and seven unmanned aerial vehicles being their total sum. As the BBC points out, we cannot know exactly what the Taliban have got their hands on because satellite images can’t be obtained from many of the airports.

Twitter can certainly provide a glimpse though, with Taliban militants gleefully posting photos and videos of their new toys. But what, realistically, could they do with the equipment? As Jacob Parakilas details in the Diplomat, while many simple weapons and vehicles — such as rifles, pistols and trucks — are easy enough to maintain and mend, modern aircraft and armored vehicles tend to require more complex care and sometimes even regular software updates.

Jodi Vitorri of Georgetown University has argued that there is ‘no immediate danger’ of the Taliban using captured aircraft. While one congressman bemoaned last week that ‘The Taliban now has more Black Hawk helicopters than 85 percent of the countries in the world’ the regime does, for now, appear unable to use them or the C-130s. They have though shown the ability to use M-16s and M-4s.

The equipment may however be passed to the highest bidder capable of using them, or to hostile states who can reverse engineer the technology and mitigate any previous Nato technological military advantages. There are other dangers too. As the Intercept’s Ken Klippenstein has reported, the Taliban has seized biometrics devices from the US military that might allow them to identify and capture Afghans who worked with Nato forces. Similarly, if reports of sensitive and classified information being left in the embassy are indeed true, then Russians, Chinese and Iranians could be among the bidders in place of mere equipment.

Hardly the resounding success some neoliberal American commentators might like to think it is.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.