Last month, Italy’s prime minister Mario Draghi promised to declassify government documents involving two organizations: Gladio, an anti-communist paramilitary group linked to Nato and the CIA, and a masonic lodge known as P2. These two groups are believed by some to have been involved in the darkest moments of post-war Italian history.

For much of the latter half of the 20th century, Italy had the unenviable position of being the epicenter of European terrorism. The blast at the Bologna train station in 1980, which left 76 people dead and more than 200 wounded, was at the time the bloodiest terrorist attack ever suffered by a European country. The bombing was pinned on a small neo-fascist militia called Armed Revolutionary Nucleus. But many Italians remain convinced that the attack emerged from a wider far-right network. Draghi’s decision to declassify the papers came on the 41st anniversary of the Bologna killings.

Post-war fascism in Italy was predicated on a ‘strategy of tension’. The term, coined by British journalist Neal Ascherson in the Observer in 1972, describes all sorts of plots, including assassinations and false flag terrorist acts, carried out with the aim — not of destabilizing the country — but of consolidating power and justifying emergency laws. When I asked Sen. Felice Casson, the prosecutor who headed the investigation into Gladio, what his opinion was of Draghi’s decision, he replied ‘Fuffa!’ — ‘just crap’. Casson explained: ‘It’s just an announcement. There is not the courage nor the will to disclose the involvement of foreign powers.’ In 2001, Guido Salvini, a judge involved in the Massacres Commission, claimed: ‘The role of the Americans was ambiguous, halfway between knowing and not preventing and actually inducing people to commit atrocities.’

The truth of such claims — denied by the US State Department — remain unverified. Perhaps Draghi’s new documents will point to greater American involvement. Certainly in the immediate aftermath of World War Two, the US took exceptional interest in Italy’s politics. The CIA has admitted giving the equivalent of over $11 million to centrist parties at the 1948 election, while there is evidence that the Americans faked letters in order to incriminate left-wing candidates. Italy was a special case among Nato countries. For one thing, it had the largest and most powerful communists party outside the Eastern Bloc, the Partito Comunista Italiano. This was intolerable to the Americans for whom Italy was strategically too important to lose.

Italian psychology at the time was shaped by the overwhelming forces of the USSR stationed just a couple of hours drive from the north eastern border. Part of the plan for an armed resistance against a Soviet invasion was Gladio, a kind of Dad’s Army of willing anti-Soviets. These so-called ‘stay behind’ units were trained in guerrilla warfare and existed throughout much of Europe. In 1991, it was revealed that Swiss Gladio members had been given combat training by the British army without the Swiss government’s knowledge or approval. Some of Gladio’s Italian members were indeed members of far-right terror groups, according to the Massacres Commission judge Guido Salvini. As in post-war Germany, where former Nazis were recruited by the Americans to fight in the Cold War, the post-war Italian government also signed up former fascists, who were the most ideologically motivated to fight communism.

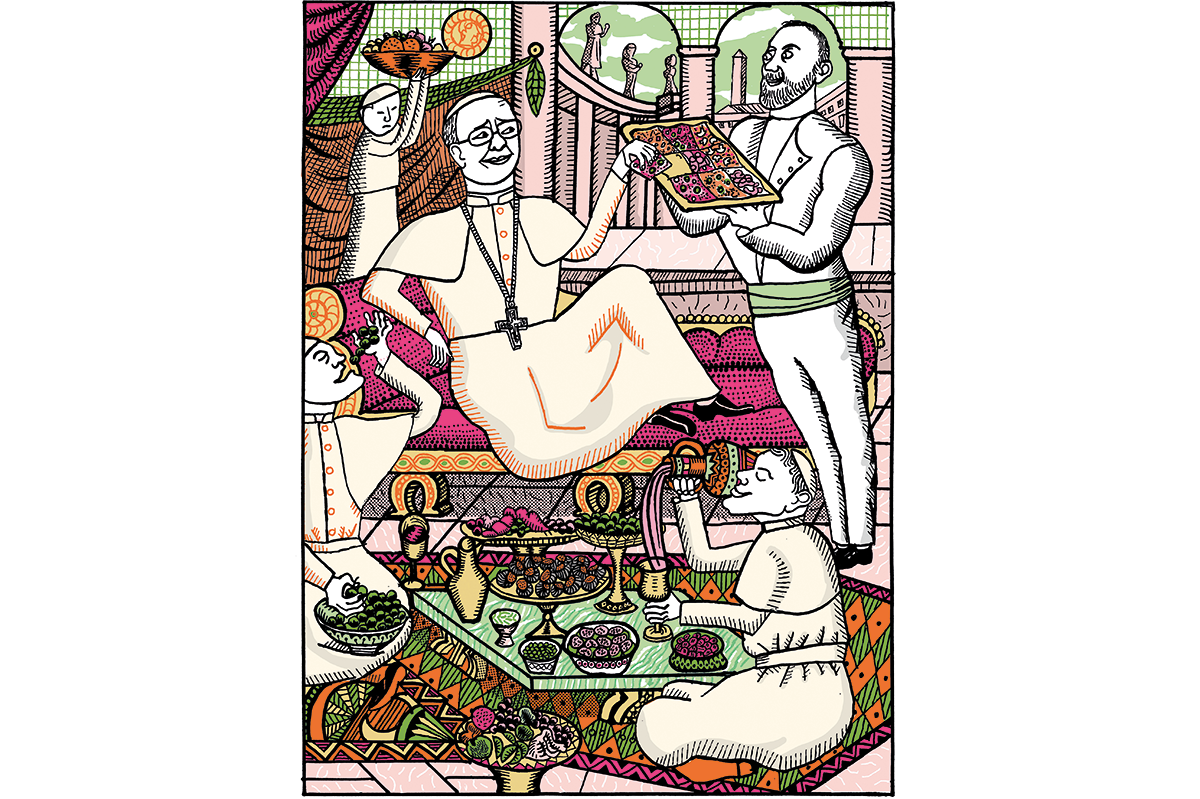

This explains the role of the masonic P2 lodge, short for Propaganda 2 (Propaganda 1 was founded in 1877 and shut down by the Mussolini regime). P2 was a secret freemason organization consisting of prominent politicians, businessmen, members of the secret service, the armed forces and influential journalists. P2’s goal was to infiltrate the state and make it impossible for the communist party to take power by democratic means. Its existence became public in 1980 and was then declared illegal shortly after in 1982. The lodge has been linked to the failed coup of the Roman prince Junio Valerio Borghese and the bombing of the Italicus train of 1974.

By the 1980s numerous corruption scandals began to surface. First came an investigation into P2 and its members, then in 1990 the existence of Gladio was formally recognized. The investigation into Gladio — first exposed at the 1984 trial of a neo-fascist terrorist — provoked outrage, but its existence proved to be of little real consequences. The Berlin Wall was crumbling and the scandal provided a useful smokescreen for the crimes perpetrated by high ranking members of the communist party. They were fearful that revelations could spill out from the disintegrating Soviet archives, revealing how the Italian communist party had been illegally sponsored by the USSR up until the late 1980s. To be subsidized by your enemy, a power hostile to the alliance to which Italy belonged, with nuclear rockets pointed at your territory, constituted a much higher treason than belonging to Nato’s secret Gladio organization.

Evocations of the fascist peril have become an effective tool in post-war Italian politics to silence adversaries. As much as he might want to get to the truth of Italy’s strange history of neo-fascism and international intrigue, there are domestic reasons for Mario Draghi’s initiative: an attempt to keep the Fratelli d’Italia at bay. Fratelli, according to some polls now the most popular party in Italy, is the successor of post-war Mussolinist tendencies. Now, however, Fratelli is attempting to present itself as a normal conservative party. Nailing it to its past, to its post-fascist roots, is good politics for Draghi.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.