Crimea matters to Russians — whether they adore or abhor Vladimir Putin — in a way none of the other claimed or occupied Ukrainian territories do, and as such the peninsula’s fate will probably be central to any eventual resolution of the current war. That some Ukrainian sources are now talking about a military reconquest in the summer campaign season and others of diplomatic solutions suggests the possibility of movement.

Whatever the official line, there are also many in Kyiv who are uncertain if they really want Crimea

To be sure, there is no fundamental shift in Kyiv’s official position, that Crimea — like all the occupied territories — must be returned to its control, and that this could be by military force if necessary, negotiation if possible. Hawkish military intelligence chief Kyrylo Budanov predicted that Ukrainian forces would be in Crimea by the end of spring, while presidential advisor Mykhailo Podolyak said at the start of this month that it was “mathematically proven” that this would happen within five to six months. However, another advisor to Volodymyr Zelensky, Andriy Sybiha, told the Financial Times this week that Ukraine would negotiate on Crimea if its spring counteroffensive was successful and its forces advanced to the mouth of the peninsula.

Others in Kyiv rushed to affirm that this did not represent a change in Kyiv’s position, let alone a hint that it might give up its claim to Crimea as part of the price for peace. Rather, they said, it was that they would rather Moscow surrender it willingly rather than be forced into it by further bloody fighting.

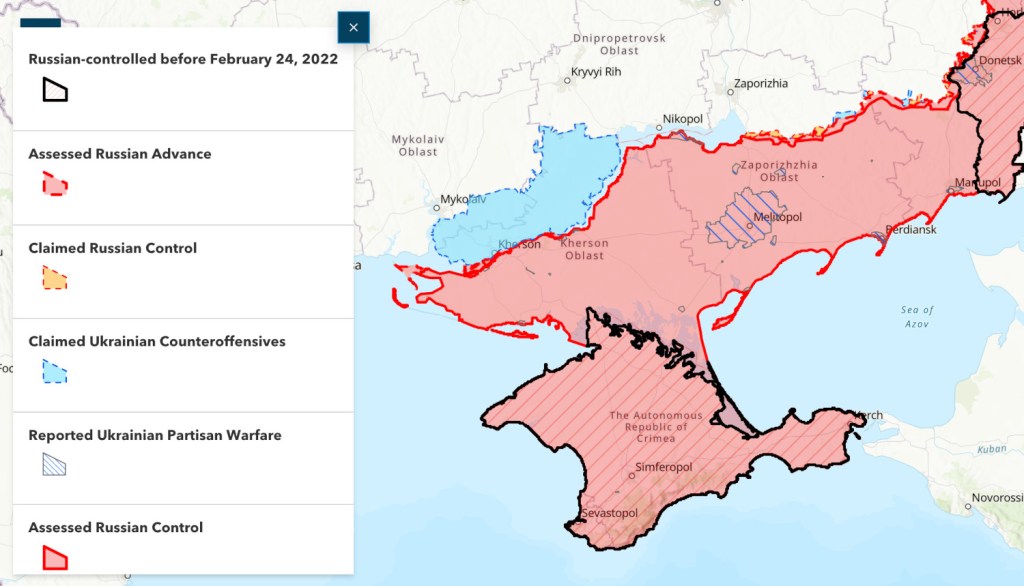

After all, despite the confident assertions of direct incursions into Crimea — which are likely a mix of bombast and mind game — Kyiv’s strategy is more likely to be to make its retention untenable. In some ways, the parallel is the liberated city of Kherson. At first, Ukraine tried a frontal assault, which proved a bloody failure, before settling in to bombard Russian positions in the city and, even more effectively, the supply lines on which they depended. Russia’s generals realised that they had no real alternative and, after weeks if not months of lobbying a reluctant Putin to this effect, finally persuaded him to approve withdrawal.

A direct attack in Crimea would be difficult, with Russian forces well-entrenched and the narrow access routes to the peninsula protected by mines, anti-tank defenses and elaborate trench systems. It might also panic Putin, who has tied so much of his political legitimacy to the seizure of Crimea, into some kind of escalation (not necessarily nuclear: this could also involve anything from a full mobilization to covert attacks on western supply lines).

However, although it is still possible that this is a feint, it looks likely that the Ukrainians will in due course strike at Melitopol, a vital hub along the so-called “land bridge,” a stretch of territory along the northern coast of the Sea of Azov, that connects Crimea to the Russian mainland. If they can break these vital road and rail links, then reinforcement and resupply for Crimea would depend on the Kerch Bridge, which has already been broken once, and vulnerable sea and air routes. This would, Kyiv hopes, make Crimea another Kherson.

Of course, Moscow still refuses to countenance any suggestion that Crimea’s future may be up for grabs. Since its unrecognized annexation in 2014 following a rigged referendum, Sergei Tsekov has represented it in the Russian senate, and his response was uncompromising: “No one will discuss ‘diplomatic’ methods of transferring Crimea from Russia to Ukraine. Crimea will never return to Ukraine.” Such bluster notwithstanding, Kyiv — and the West — hope that ultimately Putin may feel that his survival is best served by negotiation rather than risking being forced ignominiously out of Crimea.

However, there is also a final complication. Whatever the official line, there are also many in Kyiv who are uncertain if they really want Crimea. Many, and perhaps even most, of Crimea’s residents are likely to be pro-Moscow, and one Ukrainian security official admitted to me that it could “easily become our Northern Ireland,” as well as a constant source of future friction with Moscow. More to the point, if it is harder to retake than the remaining occupied territories, is it worth extending the conflict, and running the risk that western “Ukraine fatigue” will set in?

In Washington and elsewhere, there is a conviction that Crimea’s ultimate fate will be crucial to any peace talks, with Ukraine offering Moscow some give there in return for a full withdrawal elsewhere and reparations. This may, for example, entail a new and genuine referendum on its fate, even though this would be a complex undertaking, having to include those who fled since 2014 and exclude a new generation of post-annexation Russian carpetbaggers. Of course, it is too soon to talk about any potential deal, and much will depend on the outcome of the spring and summer campaigning season. However, the talk about Crimea is a sign that in Kyiv and elsewhere, people are beginning to think not just about the war, but the endgame.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.