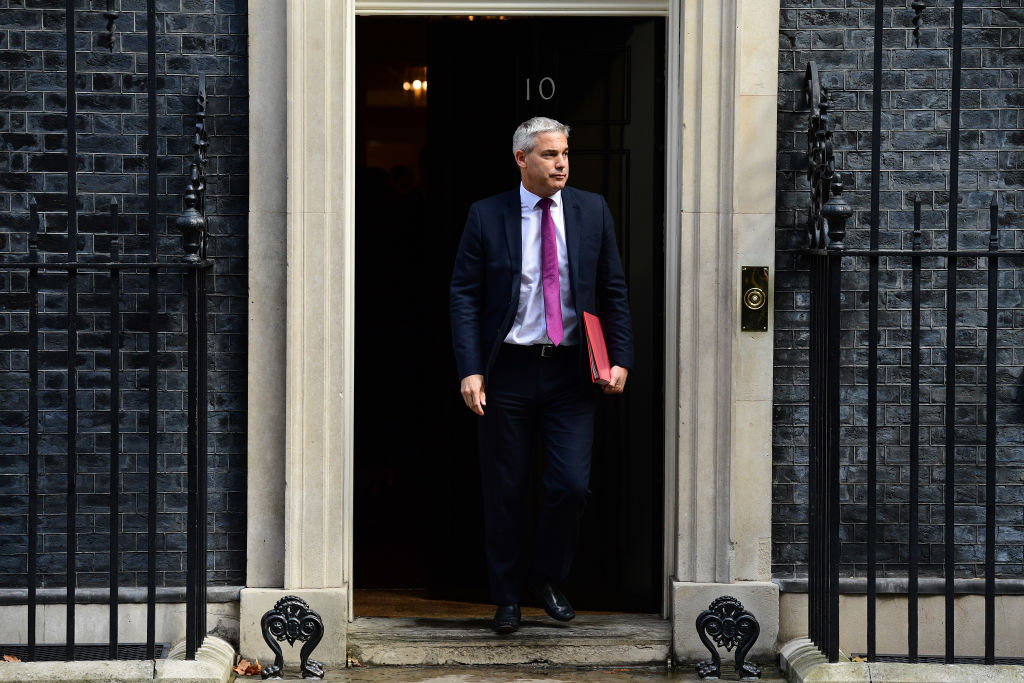

The EU side regularly points out that the British government hasn’t presented any detailed proposals on what it wants to replace the Irish backstop with. At a Cabinet committee meeting this week, the Brexit secretary Steve Barclay set about explaining to ministerial colleagues why this was. As I report in The Sun this morning, he told the committee that the EU had set three tests for any new proposal. First, it must avoid any infrastructure on the border that would be incompatible with the Good Friday Agreement. Second, it must protect the integrity of the EU’s single market. Third, it mustn’t involve any checks on the island of Ireland.

Barclay said that the UK could meet the first two of these tests, but not the third. He said that there was no point in presenting any detailed proposals until the EU shifted on the question of checks. One government source explains that if the UK did the ‘EU would nuke the proposals and we would be in chaos’.

So, the challenge for Boris Johnson is to get the EU to move on this third point. His Monday meeting with Commission president Jean-Claude Juncker offers a chance to lobby them on this very issue.

With his term as Commission president due to end on October 31, Juncker will be eager to resolve Brexit before he goes. I also understand that several EU governments, including France’s, are now apprehensive about the possibility of a second referendum. They believe it would be bad for the EU for the UK to stay in given how contested our membership now is.

The EU, though, will not abandon Ireland. This means that whatever proposal Boris Johnson comes up with will have to be something that Leo Varadkar is prepared to accept.

The first meeting between the two men has given Downing Street some hope that they can find something that works for Dublin, them and the Democratic Unionist party. The DUP’s willingness to entertain Northern Ireland continuing to follow EU rules on agriculture has opened the door to further discussions.

If parliament had not tied Boris Johnson’s hands, he could have seen if the risk of no-deal would have pushed Dublin and the EU to compromise on the checks front. But he is now negotiating with a weakened hand.

For this and other reasons, the odds are still against a deal. But there is a greater chance of one than there was a week ago.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.