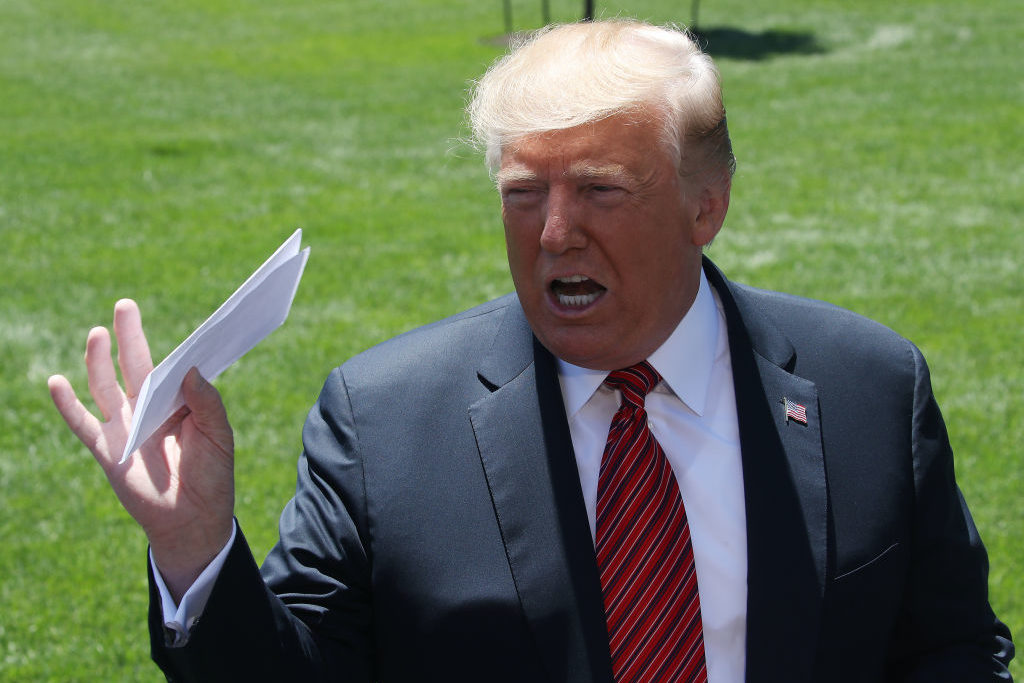

Let’s not mince words. President Trump and his loyalists were dead right. His threat of tariffs pushed Mexico to work harder to stop the Central American caravans, and the migrants who hope to exploit immigration law loopholes in order to receive asylum in the United States.

And the bipartisan, Trump-loathing political, business and media establishments were all dead wrong. They warned that his strong-arming would ignite a trade war, disrupt the thick web of supply chains linking the American and Mexican economies, and risk a recession. Equally off-base was the establishmentarians’ angst that Trump’s gambit would endanger the revamp of the North American Free Trade Agreement (Nafta) that he has sought and which Mexico and Canada recently signed.

Trump busted a ballyhooed — but entirely phony — globalist policy norm. Immigration and trade policy must kept completely separate? Seriously? When one of Nafta’s selling points is a promise that prosperity in Mexico will keep Mexicans home? All the same, I hope Trump doesn’t whip out the tariff threat again. Not because Trump’s tactics were ‘bullying’ — a childish charge that pretends coercion plays no part in international relations. And not even because further actual or threatened levies will undermine Nafta’s intended replacement, the US-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA).

Instead, I hope Mr Trump doesn’t use this weapon again because the further down the tariff road he travels, the likelier he is to forget the big picture. He should be seeking a trade overhaul with Mexico, as with the rest of the world.

Trump’s gambit vividly illustrates a fundamental truth about the global economy. For all the bloviating about interdependence and international supply chains, and commerce being a win-win proposition by definition, Trump gets that the United States needs foreign economies much less than foreign economies need the United States. He fully understands this, but the establishment doesn’t. Most journalists and politicians simply don’t understand economics. Most business and financial interests want to keep this dark, because their top priority is restoring the pre-Trump trade policy of offshoring.

Though Mexico may drag its feet on its commitments to Trump, the migrant deal is a perfect example of America’s relative power. More than a quarter of a century after Nafta’s creation, each year Mexico still sends roughly 80 percent of its exports to the United States — even though Nafta’s creators promised that Nafta would turn Mexico into an export platform that enabled American producers to reach new foreign markets. These exports, astonishingly, amount to nearly 30 percent of a Mexican economy that still isn’t remotely close to the growth needed to reduce Mexico’s widespread poverty. Given Mexico’s heavy dependence, retaliating by rejecting the USMCA would mean Mexico cutting off far more than its nose to spite its face.

So why wouldn’t boosting tariffs eventually achieve the president’s immigration aims? Why wouldn’t it be more effective than the new USCMA in bringing back more of the jobs and factories he wants to repatriate to the United States from Mexico? It might, but Trump also has another option which is economically more promising and politically more divisive. Even better, this alternative approach would aid Trump’s efforts to weaken China and steadily decouple the United States economy from the People’s Republic. And it’s a strategy that the president himself has endorsed: turning North America into a genuine trade bloc.

USMCA does a better job than Nafta of keeping the benefits of North American trade inside North America. But USCMA leaves economies outside North America, especially China, too many opportunities to sell to the enormous North American market without producing inside it or creating any jobs. Worse, outsiders enjoy these benefits without incurring any of USMCA’s market-opening obligations.

The solution is to raise North American trade barriers to imports from outside the USCMA area. The mechanism for this is the trade deal’s ‘rules of origin’. The US, Mexico and Canada should grant duty-free privileges only to goods made, or almost entirely made, within North America. This would create plenty of business and jobs in all three countries, even though commerce between them would be unfettered. Businesses everywhere would have powerful incentives to comply, by building factories inside North America in order to sell to this enormous, albeit overwhelmingly American, market.

Many of these plants and jobs would move to North America from China and elsewhere in Asia, thus contributing to Mr Trump’s trade diversion goals. And many of the industries involved would be ideal investors and employers in Mexican and Central American economies desperate for growth and jobs. How better to weaken a prime engine of illegal immigration over the long term?

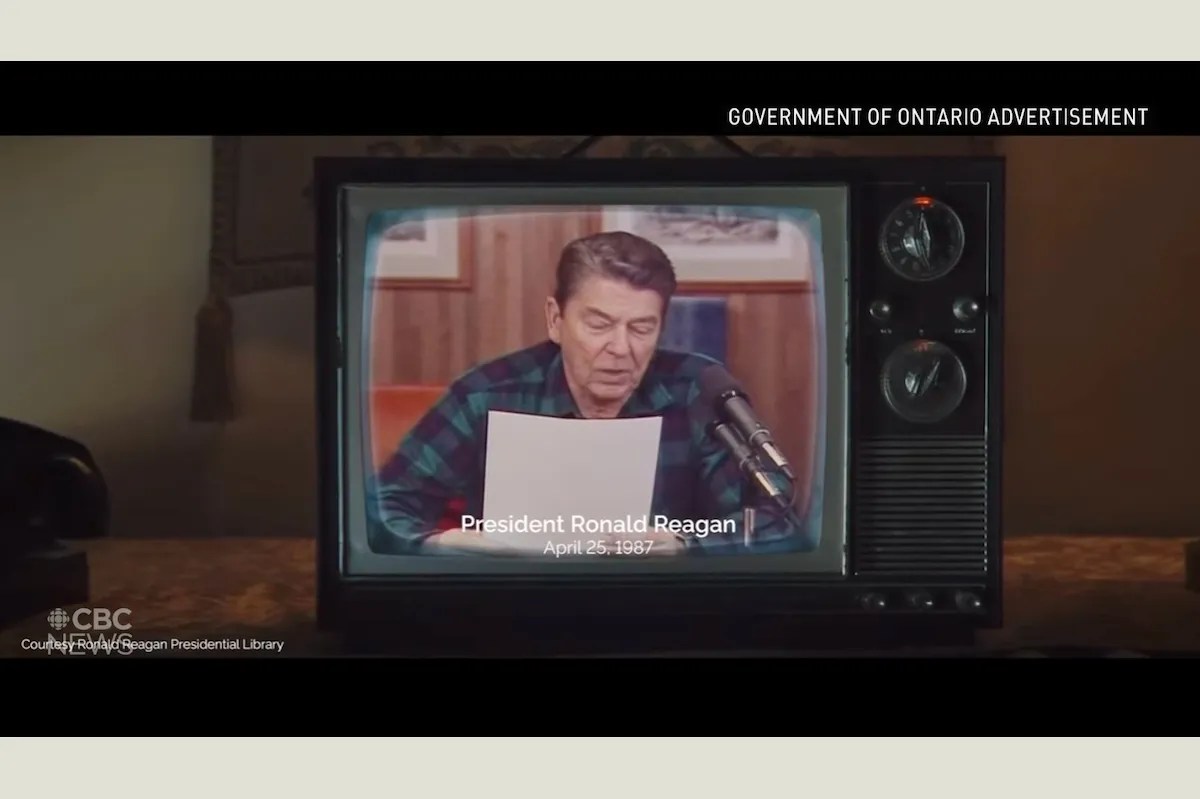

Almost as importantly, the North American trade bloc boasts a strong bipartisan political pedigree. Nafta’s two main sponsors, Ronald Reagan and Bill Clinton, both claimed North American economic integration was necessary in order to counter comparable developments and rising competition in Europe and East Asia. As Reagan correctly observed, ‘Within the borders of this North American continent are the food, resources, technology and undeveloped territory which, properly managed, could dramatically improve the quality of life of all its inhabitants.’ Candidate Trump alluded to this during a 2016 visit to Mexico City.

Dropping the tariff threat won’t deprive President Trump and the United States of leverage for ensuring Mexico’s cooperation on immigration. Iowa Republican Sen. Charles Grassley has proposed, and the president has endorsed, the idea that, should Mexico seem to be slacking off, Washington would tax remittances sent home by legal and illegal Mexican immigrants. At $30 billion annually, these transfers represent vital lifelines to millions of low-income Mexicans. And as the consequences of that tax would be felt inside Mexico, fewer hackles would be raised in the United States.

Strictly speaking, this new trade policy initiative doesn’t deserve the label ‘America First’. But this time, ‘North America First’ should be more than close enough.

Alan Tonelson is the founder of RealityChek, a public policy blog focusing on economics and national security, and the author of The Race to the Bottom.