As the level of US debt zooms past the $34 trillion mark, it has become increasingly clear that the American left has no intention of trying to help control government spending. To the extent that annual deficits must be trimmed to protect the integrity of the nation’s currency, Democrats and their allies are instead planning to go beyond the current progressive tax on income and institute a new levy on citizens’ assets.

Some such as Senator Elizabeth Warren openly advocate taking the conventional idea of a property tax and applying it to everything a person owns — cash, savings accounts, stocks, jewelry and even art. Calling for what she has termed her “Ultra-Millionaire Tax,” Warren would start by imposing a 2 percent federal tax on every dollar of an individual’s net worth over $50 million, adding a percent more on every dollar above $1 billion in net assets. Over time, the tax rates could be increased, and the amounts they cover lowered, to fund new or expanded public programs.

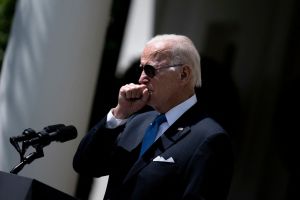

On the other hand, Democrats such as President Biden, knowing that voters are smart enough to realize that the threshold of a wealth tax could someday be dramatically lower, prefer to promote it indirectly. That is, they don’t about the need for a wealth tax, but for “tax fairness.” Biden himself takes every opportunity to complain that Americans worth over $100 million pay only 8 percent of their income in taxes each year, supposedly a much smaller percentage than their fellow citizens.

What the president and others talking tax fairness conveniently fail to mention is that their definition of the wealthy’s undertaxed income includes paper gains on investments, what neither Congress nor the IRS has ever considered real income until the underlying assets have been sold. According to a 2023 study by the Tax Foundation, the top 1 percent of taxpayers actually pay an average income tax rate of 26 percent, the top half an average rate of 14.8 percent, and the bottom half an average 3.1 percent tax rate.

There is no shortage of reasons to doubt the wisdom of a national wealth tax. Annually valuing the paintings, boats, planes, diamonds and other assets that rich people tend to accumulate would not be an easy task, either for their owners or government auditors. Innovation and entrepreneurship would suffer, both from the reduced pool of capital available to startups and from the lower expected return on investment. And while family businesses often look prosperous in their annual reports, many would be hard pressed to raise extra cash for a yearly wealth tax.

But perhaps the best reason to be skeptical of a wealth tax is that it has already been tried multiple times in Europe and clearly found wanting. In 1990, as many as twelve OECD countries had a net worth levy on their books, but just a decade later only Norway, Spain and Switzerland had kept the legislation. And of those three, only Switzerland had managed to make any money from it.

Still, American progressives believe that the recent experience of European nations is not a useful predictor of how well a wealth tax would work at home. They note that the countries which ultimately rejected it are much smaller than the US, which meant that their richest citizens could easily avoid the levy by establishing residence in a tax-friendlier territory nearby. In the case of France, for example, an estimated 42,000 millionaires fled that nation’s wealth tax to Belgium and other jurisdictions, eventually forcing President Emmanuel Macron to rescind it.

As UC Berkeley economist Gabriel Zucman, who helped design Warren’s plan, has argued, it would take a much bigger effort to escape the reach of a wealth tax in a continent-sized country like the US. And even those rich Americans who could pull it off would not likely trade their citizenship for another country’s more lenient tax regime, at least not in the beginning. Furthermore, those wealthy who were willing to make the move could be made subject to an “exit tax” which would confiscate a high percentage of their net worth.

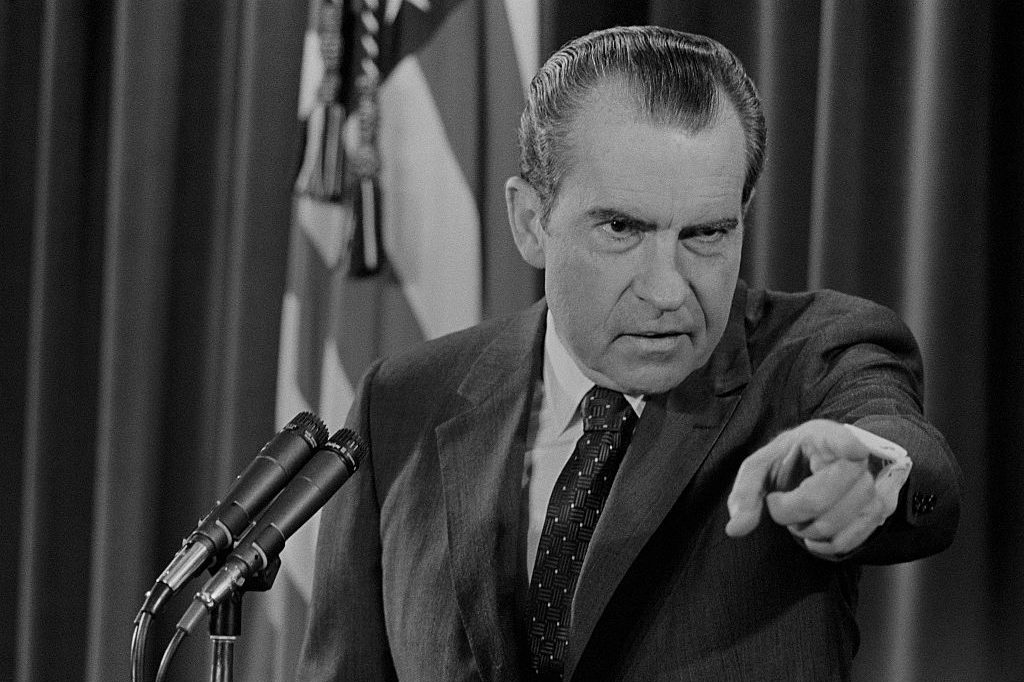

History does provide some evidence that progressives are right, at least about a larger political entity being better able to enforce a wealth tax. Between the reign of Emperor Augustus (31 BC-14 AD) and that of Diocletian (285-305 AD), the Roman Empire suffered its own version of America’s current out-of-control spending. As former City University of New York professor Joseph Peden has documented, the Roman army had more than doubled (from 250,000 men to 600,000) during the period, and the imperial court had divided into four administrative regions, each requiring its own palace, staffs and Praetorian Guards.

At first, the government was able to pay its bills by gradually diluting the silver content of the most widely used coin, the denarius, from 95 percent to a mere half of one percent — the ancient version of inflation. But by the time of Diocletian, public expenditures had grown to the point where the state began taxing various forms of wealth. Not just farmland but eventually the inventory and working capital of merchants, the gold held by both individuals and city treasuries, and even the handiwork of craftsmen and artists.

The reach of Diocletian’s authority, from Britain in the north to Egypt in the south and from Spain in the east all the way west to modern-day Iraq, did indeed make it possible for successive emperors to enforce and expand asset levies. Diocletian himself organized a special force of revenue police to make sure every man’s property and possessions were fully taxed. And according to historian Will Durant, even torture “was used upon wives, children and slaves to make them reveal the hidden wealth and earnings of the household.”

But rather than cure Rome’s financial problems, the imposition of wealth taxes began a long struggle between the needs of a continually expanding bureaucracy and an ever more impoverished citizenry, a struggle which contributed greatly to the empire’s eventual fall. As many fled occupations which wealth taxes rendered unprofitable, for example, the government passed laws which made all professions hereditary, regardless of whether anyone could now make a living at them. “If your father was a shoemaker,” as Professor Peden put it, “you had to be a shoemaker.’’

And as overtaxed Romans began abandoning heavily assessed properties and even taking demotions in social rank to avoid the elite’s expected subsidy of civic works, emperors sharply increased inheritance taxes and forced many to become tax collectors themselves — with the obligation to make up for any shortfall. Today it is still widely imagined that Rome fell to the overwhelming power of invading German tribes, but the historical evidence suggests that its citizens simply found it more economical to switch sides. By the start of the fourth century, according to Durant, thousands of tax migrants were fleeing over the Empire’s northern border “to seek refuge among the barbarians.”

Modern progressives undoubtedly imagine themselves capable of balancing the revenue from a wealth tax against any seriously negative social effects such a tax might produce. But recent studies have shown that even seizing every dollar of every US billionaire would fund the federal government for only nine months. And if there is any lesson to be learned from ancient Rome, it is that once the government starts expanding wealth taxes to include the less affluent, its sympathy for those who pay it is not much of a control on bad policy.

The European countries which experimented with a wealth tax in our own time were able to pull back from it because they were small enough to have lost too many affluent taxpayers to neighboring nations. But history’s prognosis for the consequences of a US wealth tax is not nearly as rosy.

Leave a Reply