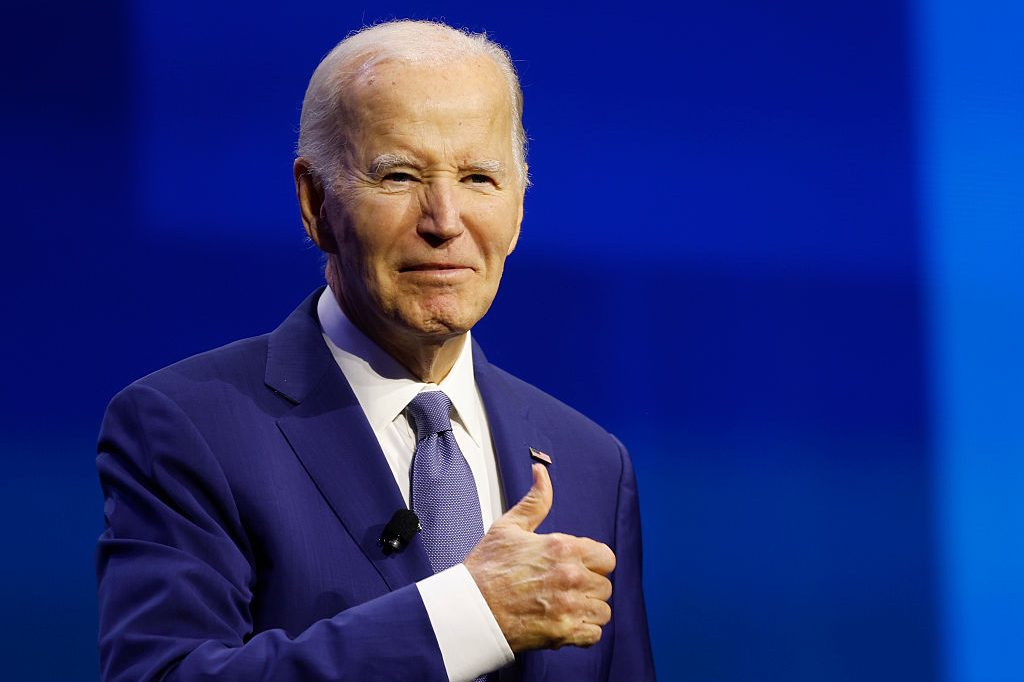

The idea of a Saudi-Israel rapprochement would have been unthinkable not so long ago, and yet, shortly before the October 7 attacks, it was on the cards. The Emirates and Bahrain had recognized Israel’s sovereignty. Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman was positioning Saudi Arabia to do the same. Now Joe Biden — who on Tuesday said he was “outraged” at a convoy strike that killed seven people — is desperately trying to see if he can get things moving again.

Jake Sullivan, the White House national security advisor, is in Saudi Arabia this week meeting with MbS in a last-ditch attempt to save Biden’s grand design for Middle East peace. He’s unlikely to succeed, but the manner of the failure could determine how the next stages of the war between Israel and Iran and its regional proxies play out.

The president wants to show his own restive Democratic Party that he’s trying to end the war

The contours of the Biden administration’s plans are well-known. Israel agrees a timetable for a ceasefire in Gaza and allows a “revitalized” Palestinian Authority to assume control of the devastated strip. Israel also commits to serious negotiations about a Palestinian state in Gaza and the West Bank. The Saudi kingdom “normalizes” its unofficial relationship with Israel, and signs a strategic co-operation agreement with the US, giving it unprecedented access to American arms and even a civilian nuclear program.

For Biden this would be the crowning foreign-policy achievement not just of his presidency, but of his long public career: ending the war in Gaza, solving the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and creating an American-friendly security partnership in the Middle East, led by its two main allies, Israel and the Saudis, to counter Iran. But there are too many obstacles to realizing his vision.

Israel’s objective of destroying Hamas’s military capabilities in Gaza is still far from realized six months on. Benjamin Netanyahu has ruled out a role for the Palestinian Authority in Gaza once Hamas has been vanquished and it’s by no means clear that the Authority can be “revitalized” under the sclerotic rule of its eighty-eight-year-old president Mahmoud Abbas. A new government was formed this week in Ramallah with a new prime minister, Mohammed Mustafa. But the sixty-nine-year-old American-educated economist is hardly a fresh face who will challenge the other time-servers. He served as Abbas’s economy minister and chairman of the Palestine Investment Fund: he’s business as usual.

And while the Saudis are interested in a strategic alliance with the US, and, along with the Emiratis, may be prepared to foot the bill for rebuilding Gaza’s ruins — assessed by the World Bank as costing at least $18 billion — it remains to be seen how determined they are to take on Iran whose leaders will do all they can to disrupt the American plan.

On Monday, an Israeli air strike destroyed the Iranian consulate in Damascus, killing seven officers of the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps, including General Mohammad Reza Zahedi, commander of the expeditionary Quds Force in Syria and Lebanon. Zahedi was also the senior representative to Lebanese Hezbollah, Iran’s most powerful proxy, which has been waging a low-intensity war with Israel since the Hamas attack.

The strike was a reminder that Israel is fighting at least two wars simultaneously. While the Gaza war is aimed at ending Hamas’s rule there, Israeli objectives to the north are still undefined. Hezbollah is a much larger force that effectively controls Lebanon. Israel’s military is more powerful, but an all-out war with Hezbollah would lead to major damage to Israeli cities from thousands of Iranian-supplied missiles. Hezbollah stands to lose its dominance in such a war too. Which is why Israel has taken a calculated risk in targeting the group’s Iranian patrons on Syrian soil, driving home the message that Israel is determined to limit Hezbollah’s influence on its borders.

Israel’s security and political establishments are split over the Biden plan. Netanyahu has made no secret of his desire to deliver an agreement with the richest, most influential Arab nation, but at present refuses to pay the price the Saudis demand — a role for the Palestinian Authority in Gaza and negotiations towards a two-state solution. This is not only because of his personal resistance to any concessions, but also because his far-right coalition partners would bring down his government if he agreed.

The pragmatic wing of the emergency coalition, namely ministers Benny Gantz and Gadi Eisenkot, who joined the war cabinet when the conflict began, are more open to the idea, though they haven’t said so in public — yet. They are backed by many security chiefs as well. “Israel has a chance to emerge from this war with a new regional framework in which the major Arab regimes join it against Iran,” says one general. “But it won’t happen if the politicians miss the opportunity.”

Biden is pushing through despite knowing the chances, for now, are slim. He wants to show his own restive Democratic Party, which is increasingly critical of his support for Israel, that he’s trying to end the war. If MbS gives the green light, the president may publicly present the plan, leaving Netanyahu to either reject it or, though it seems unlikely, accept it as a last resort to save his own tarnished legacy at the price of his coalition. But above all, Biden is giving it another try because he believes in his plan, just as he believes he will beat Donald Trump in November and secure a second term.

By then, Israel will have been at war for more than a year and many expect Netanyahu will not be able to prevent an early election, which he will almost certainly lose. The next Israeli PM may be more amenable. The only thing Biden knows for sure is that this time next year, MBS, who doesn’t have to submit himself to the indignity of elections, will still be in charge of Saudi Arabia. So he’s trying to lock him in while he can.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazines. Subscribe to the World edition here.

Leave a Reply