How do you take your coffee? With cream? Sugar? A splash of white shame?

“The unbearable whiteness of coffee” is the click- and race-baiting headline of a Fast Company article that’s making the internet rounds (my innocent online purchase of Chemex coffee filters must have prompted this suggested guilt trip). I really didn’t want my most sacred morning ritual — and bright spot of many afternoons, for that matter — to be added to the list of things I shouldn’t enjoy because it’s racist. So I poured myself a large mug of fortifying Joe — potentially my last — and gripping it tightly, read the dreaded article and did some digging.

What I gleaned was a double shot of good news for coffee lovers and non-coffee drinkers the world over: what the piece and a half-dozen articles on the history of coffee revealed is that coffee is not “unbearably white” (whatever that means). What’s more, the fact that progressives are resorting to spreading misinformation about a beverage that’s been a universal delight since around 700 AD shows they’re really scraping the bottom of the coffee pot; the race war must be withering.

“Coffee was stolen from African plantations by Europeans in the 1600s, incorporated into the transatlantic slave trade in the 1700s, and today is a $100 billion industry run mostly by white executives,” the article alleges.

But not only could I find no other source that makes mention of coffee’s “dark past,” the writer also blatantly omits what every other account on the subject generally agrees upon: the story of coffee’s proliferation is electrifying and unifying (especially for America), not racist.

Coffee was discovered in Ethiopia. One legend credits dancing goats with revealing the stimulating effects of caffeine and says monks used coffee early on to help them stay awake during long hours of prayer. From Ethiopia, it quickly spread to Yemen and across the Middle East.

From there, coffee caught on in the Far East and West, eventually arriving in the New World with French Navy Captain Gabriel Mathieu de Clieu, who obtained a seedling from King Louis XIV’s coffee tree (a gift from the Mayor of Amsterdam).

According to the National Coffee Association of USA:

Despite a challenging voyage — complete with horrendous weather, a saboteur who tried to destroy the seedling, and a pirate attack — [de Clieu] managed to transport [the seedling] safely to Martinique. Once planted, the seedling not only thrived, but it’s credited with the spread of over 18 million coffee trees on the island of Martinique in the next fifty years.

America’s history with coffee, like its country, is rich in rebellion. Tea was, of course, the preferred drink by British colonists — until the Boston Tea Party. “After tea became a symbol of oppression in the colonies, thanks to the Boston Tea Party in 1773, coffee drinking became more popular,” chronicles coffeeaffection.com. “It was considered un-American to drink tea; coffee was the drink of true patriots.”

And so it continued. Teddy Roosevelt was rumored to have drunk a gallon of coffee a day. According to PBS, “Roosevelt is also said to have coined Maxwell House’s famous ‘Good to the Last Drop’ slogan after being served the coffee at Andrew Jackson’s historical home, the Hermitage, in Tennessee.”

It is hard (and unpleasant) to imagine a world without coffee. The little berry has changed so much about society, having created a whole culture of coffee and conversation, bestowed a range of health benefits, and personally granted me the ability to function each day. Coffee is a top traded world commodity, accounting for more than $100 billion globally, and words of praise for this wonder drink span ages, races, genders, and decades.

All this is to say that coffee is a peppy medicine of the masses — of all people — those the color of Starbucks’s darkest roast to their flattest white and every hue in between. And it’s a beautiful thing. Like oil and grain, coffee is something people all over the globe find useful and, I may venture to say, necessary. Even if coffee’s past contains some less than proud moments — there were no doubt plenty of instances of abuse regarding its early trade — Fast Company’s attempt to use this time-honored, unifying creation to dig up more dirt than Amber Heard and Johnny Depp’s divorce lawyers, and stir up controversy over something that “is said to have happened” 422 years ago, is as shameful as Jussie Smollett’s hate crime hoax.

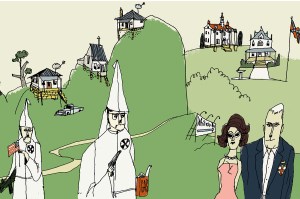

Though racism unquestionably still exists in America, race relations have improved immensely since the civil rights movement. I would wager the “unbearably white” vibe of her neighborhood coffeeshop was not a concern for heroes like Rosa Parks, who were engaged in real race wars. Fast Company should, by all means, spotlight and celebrate coffeeshops that are “connecting [their] products to black culture,” but why invent new grievances when we’ve made such progress overcoming decades of divisions?

Coffee, an egalitarian, inclusive form of comfort beloved by the whole planet, should bring us together, not drive us apart. Instead of “reclaiming” and “rebranding” coffee culture, can’t we try sharing it? It is my hope, anyway, that if the dubious history of coffee plant theft in the 1600s is a headline-worthy race concern these days, it’s a sign we’re on the right track in the race relations department.