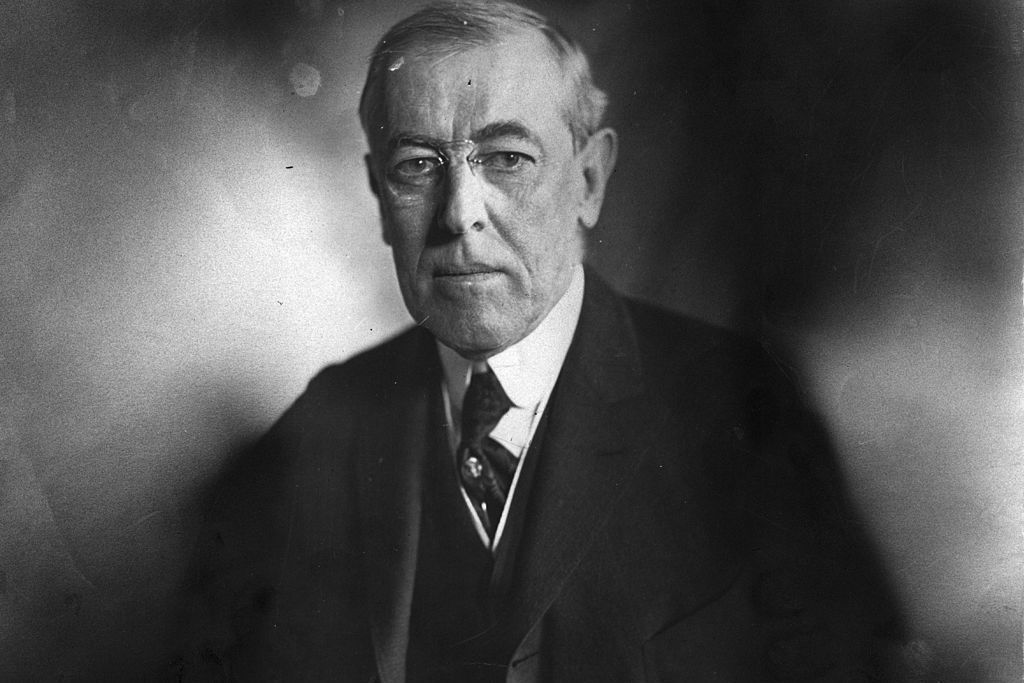

Woodrow Wilson can’t seem to catch a break. Since Princeton University’s 2020 decision to remove the name of the former president (both of the United States and the university) from its school of Public and International Affairs for his “racist thinking and policies,” other academic institutions have followed suit. An elementary school in Trenton, New Jersey, decided in May to drop his name because of Wilson’s “racist values.” Another school in San Leandro, California, made the same decision, as has a high school in our nation’s capital.

There’s more than a little irony here. Wilson, racist though he was, was also a leading champion of the progressive, globalist worldview shared by our technocratic elites. He pursued a policy of “Moral Diplomacy,” encouraging democratic reforms and American-assisted “self determination.” Our nation’s high-schoolers learn of his famous assertion in a 1917 speech to Congress that “the world must be made safe for democracy.”

Less well known is his role in the progressive project to refashion government into an administrative behemoth governed by unelected experts. In 1891, he wrote that “the functions of government are in a very real sense independent of legislation, and even constitutions.” In an even earlier 1886 essay, he declared, “The field of administration is a field of business. It is removed from the hurry and strife of politics; it at most points stands apart even from the debatable ground of constitutional study.” In other words, the very same diversity, inclusion, and equity technocrats that decry Wilson owe their esteemed status to him.

But that’s not the only irony, as the late scholar Angelo M. Codevilla explains in his posthumously published America’s Rise and Fall Among Nations: Lessons in Statecraft from John Quincy Adams. America’s foreign policy elites pursue what is essentially a Wilsonian progressive project abroad, conducted with the same bureaucratic independence and unaccountability envisioned by Wilson, aiming to remake the world in our image while simultaneously condemning the very same America they claim to represent. Codevilla observes, “Obsessed with themselves, they also came to despise America’s unique culture and history.”

As I argued in an earlier piece at the Spectator, the American foreign policy establishment has made the United States into a global busybody neighbor. Our embassies provocatively fly the Pride flag as part of our mission to “respect and promote the equality and human dignity of all people including the LGBTQIA+ community.” We have the gall to proclaim “never again” to instances of genocide and ethnic cleansing while American companies make billions of dollars in a country that is systematically eradicating an ethnic and religious minority.

Perhaps then we shouldn’t be surprised that America’s standing in the world has declined. Pew polling conducted last year found that most people around the world think the United States is no longer a good role model for democracy. Though global opinion of the United States improved following Biden’s election, in many developed nations, including some of our closest allies — the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, Germany, Japan — it remains below what it was prior to 9/11. Those numbers are even worse when respondents in Western Europe were asked if they feel the United States considers their interests when making foreign policy. About two thirds of respondents said we don’t.

Strange that a foreign policy establishment that perceives itself as promoting “global citizenship” is viewed with suspicion and disdain by much of the globe. Perhaps, as Codevilla suggests, it has something to do with the fact that our technocrats exhibit the same style of elitist condescension towards other nations and cultures as they do towards the American citizenry. “Our foreign policy establishment gurus haven’t noticed their own lack of international standing,” Codeville argues. “Obvious contempt for the general run of humanity is the Progressive class’s distinguishing feature.”

What, then, is the solution? Codevilla argues we must return to the foreign policy realism and restraint exemplified by President John Quincy Adams, a foreign policy consistent with that of the Framers. The Federalist Papers certainly urged foreign policy restraint. No. 4, written by John Jay, says:

But the safety of the people of America against dangers from FOREIGN force depends not only on their forbearing to give JUST causes of war to other nations, but also on their placing and continuing themselves in such a situation as not to INVITE hostility or insult; for it need not be observed that there are PRETENDED as well as just causes of war.

George Washington’s warnings in his 1796 presidential farewell address regarding “foreign entanglements” are also well known.

Adams continued that legacy. He claimed that “the most important paper that ever went from my hand” was his reply to Russia’s envoy declaring that “each Nation is exclusively the judge of the government best suited to itself, and that no other Nation may justly interfere by force to impose a different Government upon it.” He promoted a foreign policy of independence and unilateralism, reinforced by the Constitution’s requirement for at least two thirds of the Senate to approve treaties. In 1821, he wrote that America “respected the independence of other nations, while asserting and maintaining her own.”

Our sixth president endorsed a foreign policy that aligns with the scholastic concept of the order of charity: one’s duties and affections are ordered in a hierarchy according to natural duties and proximity. “The peoples on our borders and on the islands around us concern us most, followed by the oceans, then the rest of the world… Justice within families and countries means maintaining proper order among their parts’ just claims,” explains Codevilla. This is exemplified in Adams’ role in formulating the Monroe Doctrine, which asserts that the United States’ geopolitical priorities — specifically in the Western Hemisphere — are based on proximity.

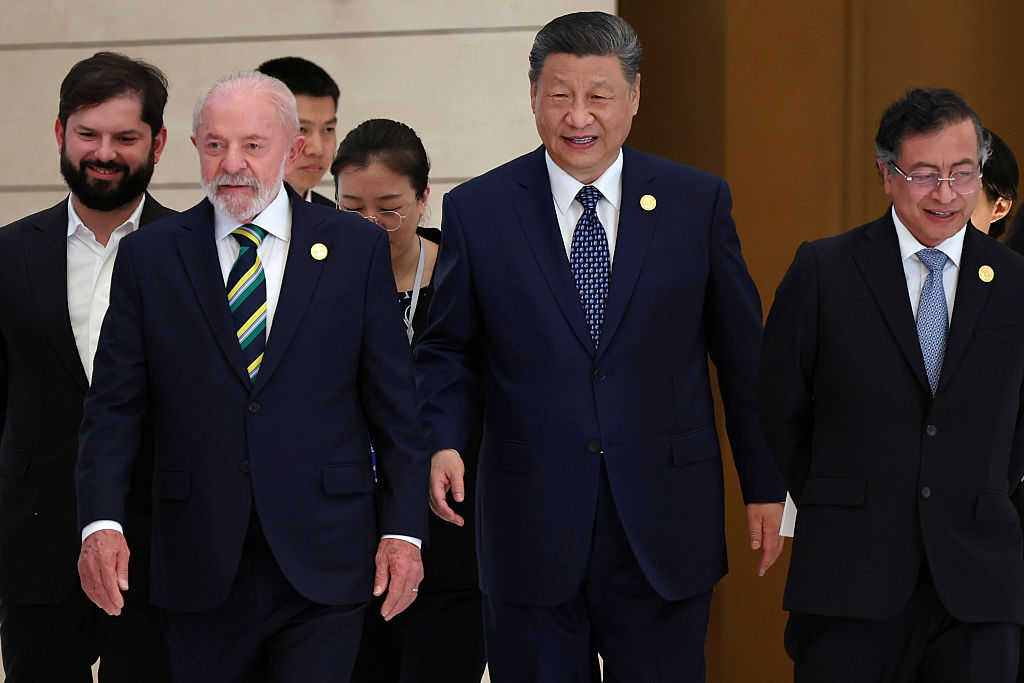

What would this look like today? Codevilla suggests that Adams would focus US security interests on naval supremacy aimed at defending the homeland rather than projecting power around the world. He would extract the American military from places that have outlived their utility. He would endorse protective tariffs that ensured American political and military independence. In contrast, notes Codevilla, “China is now the primary source for U.S. basic pharmaceuticals, electronics, and the rare earths for modern batteries.”

One of the great songs of the Sixties anti-war movement was the “I Feel Like I’m Fixin’ to Die Rag,” by Country Joe & the Fish. As the chorus goes:

And it’s one, two, three,

What are we fighting for?

Don’t ask me, I dont give a damn,

Next stop is Vietnam…

What is America fighting for? The establishment answer is the latest progressive cause — LGBTQ+ rights, female education in Afghanistan, the Rohingya of Burma — patronizingly communicated and directed by our expert meritocratic class. Wilson would be proud.