Stanford professor Paul Ehrlich’s recent appearance on CBS’s 60 Minutes reminds us what can happen when those with impressive academic credentials begin making end-of-the-world predictions.

It was 1968 when Ehrlich published The Population Bomb, a book that declared with absolute certainty that “the battle to feed all of humanity is over.” Because so many people were living so close together and consuming so much of the world’s limited resources, the inevitable future was one of “mass starvation” on “a dying planet.” A year after the book’s publication, Ehrlich went on to say that this “utter breakdown” in Earth’s capacity to support its bulging population was just fifteen years away.

For those of us still alive today, it is clear that nothing even approaching what Ehrlich predicted ever happened. Indeed, in the fifty-four years since his dire prophesy, those suffering from starvation have gone from one in four people on the planet to just one in ten, even as the world’s population has doubled. More importantly, there have been great advances in fertilizer potency, the genetic modification of seeds, irrigation, and related farming techniques.

What did happen is that those who believed in Ehrlich’s predictions caused a different but very real suffering. According to Smithsonian Magazine, Ehrlich’s book inspired the International Planned Parenthood Federation, the World Bank, and other groups to undertake cruel depopulation programs throughout the 1970s and ’80s. In Mexico, Bolivia, Peru, Indonesia and Bangladesh, millions of people were sterilized, often against their will.

In India, many states required sterilization in order for citizens to obtain water, electricity, ration cards, medical care, pay raises, and even an education. And in China, according to Smithsonian author Charles Mann, a “one-child” policy led to as many as 100 million forced abortions, often in unsanitary conditions, causing needless infections, sterility, and even death.

Unfortunately, Paul Ehrlich was not the first presumed expert to foretell a world-shaking catastrophe that would inspire the most awful of “remedies.” In 1798, a British writer named Thomas Robert Malthus published his own warning about the growth of the world’s population, arguing it would inevitably outpace the food supply and lead to famines, wars, mass poverty, and eventually rapid depopulation.

Just as with The Population Bomb, the dire prophecy outlined in Malthus’s widely read Essay on the Principle of Population failed to come true. But not before convincing many of his countrymen to stop supporting charities for the indigent and, in 1834, persuading British Parliament to pass the New Poor Law, which cut back relief for the destitute and limited its provision to the very workhouses novelist Charles Dickens famously condemned.

The latest end-of-life-as-we-know-it scenario is, of course, climate change, and its weaknesses have already become apparent. Its first predictions about the rapid extinction of polar bears and the death of the Great Barrier Reef have not only proved false, but both are flourishing more than ever. And despite the alarmist media death counts following every hurricane or other natural disaster, the OFDA/CRED International Disaster Database estimates that the real number of 2022 climate-related fatalities will be the lowest in twenty years.

At the same time, carbon-capture, making biomethane from organic waste, producing diesel from low-carbon waste, making fuel from hydrogen, and other promising technologies for reducing atmospheric pollution continue to make progress — and in many cases with financial support from the “evil” oil companies themselves.

Yet climate fear persists, driven in no small part by the entertainment industry. Just go to the science fiction section of Netflix and note the large number of films and series based on the premise of an approaching environmental apocalypse. And nearly all the non-fiction books and articles on climate change, which we might expect to take a more sober approach, ignore the fact that even if all the current efforts to produce carbon-free energy sources were to fail, we already have a good fallback in nuclear power.

Unfortunately, the exaggerated fear of climate change, just like the fears raised by Malthus and Ehrlich, is causing its own harm. According to a special 2020 issue of the Journal of Anxiety Disorders, the constant warnings of environmental catastrophe have led to what mental health professionals call “passive anxiety,” in lay terms, a constant worrying over events one feels helpless to stop. And not just among those who live in states like Florida and Oklahoma, which are frequently hit with severe weather. The panic attacks, insomnia, obsessive thinking, substance abuse, and depression associated with passive anxiety are widespread.

The two demographics that seem to be suffering most from this disorder are those with preexisting psychological problems and those under thirty who know they would be most likely to endure the horrors of an increasingly unlivable planet. Judy Wu of the University of British Columbia has become concerned about the second group. She is calling for a robust effort “to mitigate the effects of climate anxiety and stress on the short-term and long-term mental health of young people.” A 2021 study by the research group Avaaz found that over half of those between ages sixteen and twenty-five believe humanity is irrevocably “doomed” because of climate change.

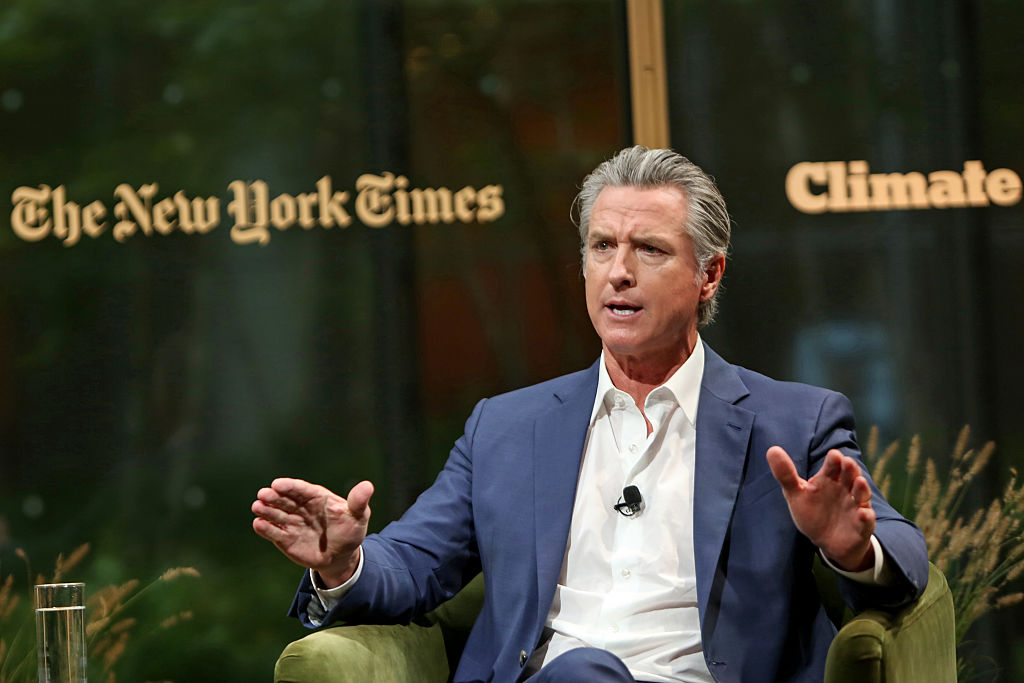

Unfortunately, the fear of a looming climate catastrophe has produced not only needless emotional pain but foolish legislation as well. As Toyota Motors president Akio Toyoda recently confided to reporters, the trillions President Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act plans to spend on boosting the use of electric cars will most likely be completely wasted. Toyoda and his auto industry colleagues know full well that battery-powered vehicles have limited range, are expensive, and recharging them is both time-consuming and costly. Most keep quiet, he said, only because they “think it’s the trend, so they can’t speak out loudly.”

Similarly in Europe, where France, Germany, Spain and other governments have passed sweeping laws to accelerate the deployment of solar panels and wind turbines. In places like the Galician countryside of northwest Spain, for example, tourist organizations have had to organize to stop and even dismantle the threat to their livelihoods from what they call “green eye pollution.”

Perhaps the most helpful way to understand the current debilitating obsession with climate change is to go back to a time when another movement to stave off global catastrophe should have had the same cultural impact, but never quite did. I am thinking of the 1950s, when the United States and the Soviet Union were both armed to the teeth with nuclear weapons, which could have destroyed the world many times over.

Certainly, there was a prudent concern back then about what might unintentionally happen. Schoolchildren were drilled in how to hide under their desks to reduce their exposure to radiation fallout, and groups like the Committee for a Sane Nuclear Policy (SANE) led protests around the world to demand unilateral disarmament. Yet the fears we see today of a carbon-drenched atmosphere never developed with the same intensity or influence in the 1950s. Indeed, it was during this period that public support for nuclear power plants and other peaceful uses of atomic energy was at its peak.

Part of this undoubtedly had to do with the fact that the country had just recently won World War II and was confident about its future. Without dismissing the need to treat atomic power with respect, its citizens were optimistic about their ability to harness science for the greater good.

It also helped that the financial incentives of the time, what President Eisenhower famously called the “military-industrial complex,” were on the side of the US containing Russia’s nuclear technology, not abandoning its own. By contrast, today’s net-zero believers get considerable marketing support from the growing number of companies with a vested interest in government subsidies to replacing fossil fuels with their own products.

And finally, we cannot overlook that the 1950s were the high point for spiritual belief in America, at least as measured by parish affiliation and attendance. Unlike now, fewer people were ready to believe that their God would let centuries of admittedly difficult but steady progress just evaporate in some meaningless catastrophe.

We may think ourselves more intellectually sophisticated today, but the price has been a dramatically increased vulnerability to the worst projections of our supposed understanding. Paul Ehrlich today is regarded by many as a false prophet; how long until we acknowledge the others in our midst?