A scandal-prone president of tepid popularity and questionable health sits in the White House. The Republicans hold a majority in the House of Representatives, but a dissident faction of 20 opposes the establishment candidate for speaker and demands greater powers for the party conference. For the first time in living memory, the favored candidate loses election on the first ballot, then on the second, then the third, fourth, fifth, and sixth.

Yes, Washington certainly was a messy place in 1923, exactly a century ago. That was when the GOP was mired in a predicament similar to the one Republican leader Kevin McCarthy finds himself in this week.

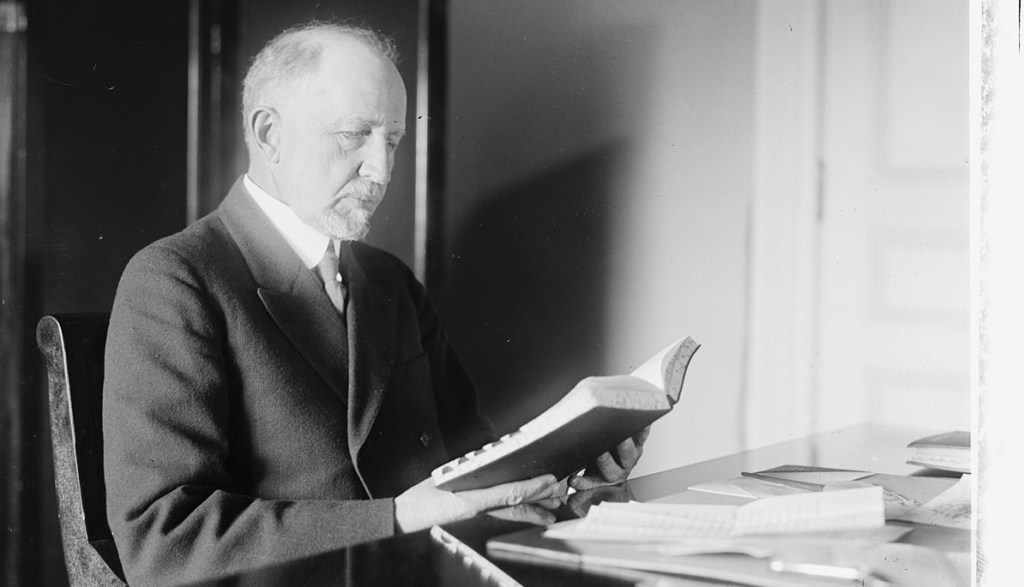

Back then, the troubled candidate for speaker was Massachusetts Representative Frederick H. Gillett. Until shortly before the first ballot, there was no reason to think he would be a controversial choice. Gillett had been in Congress for 30 years and pulled off the remarkable feat of offending no one. His only notable legislative initiative had been to propose a failed constitutional amendment to outlaw polygamy. Late in life, he’d married a respected colleague’s widow and eventually wrote a scholarly biography of her late first husband’s father. When the disputed vote came after the midterm elections of 1922, he was actually the incumbent House speaker, first elected to hold the gavel in 1919, and having sailed through two uneventful terms. A reporter summed up his mild character by writing that Gillett did not drink coffee in the morning “for fear that it would keep him up all day.”

No other House speaker had lost on the first ballot since 1859, during the extraordinary circumstances leading up to the Civil War, when New Jersey Congressman William Pennington endured 44 votes before he won. Pennington, who was elected to the top job as a freshman member, proceeded to lose reelection to the House in the fateful election of 1860 after backing a proposed amendment that would have prohibited any constitutional change to so-called “domestic institutions,” a popular euphemism for slavery. Within a year, as war approached, he died from a morphine overdose in glamorous Newark.

Pennington’s successor, Galusha Grow of Pennsylvania, technically lost on his first ballot, but before the House clerk announced the results, his closest challenger withdrew and endorsed Grow, allowing him a first-ballot win. Grow is best known for his pre-speakership exploits, which included provoking a brawl in the House chamber that involved some 50 members and, later, getting arrested by DC cops just before fighting a duel with a North Carolina congressman. Grow’s tenure as speaker was also ill-fated. In the 1862 midterm elections, he lost his congressional seat — the last time a sitting speaker would be voted out until Tom Foley’s humiliation in 1994. (Grow returned to Congress in 1894 and served four more terms. Foley became a lobbyist and was consoled with the ambassadorship in Tokyo.)

What was Gillett’s problem? Then, as now, the Republican Party faced an identity crisis. Its traditional leadership was being challenged by an emerging progressive wing, which found common cause with Democrats advocating broad reforms. The GOP progressives became especially energized after World War I, when America was thrust into an unavoidably larger international role that the traditionalists were hard put to reject. At issue during Gillett’s renomination was the rules governing the House, with the progressives demanding a devolution of authority. Sound familiar?

Gillett did not give in, and the GOP dissidents — 20 of them, to be exact — denied him sufficient votes to win the required majority. Over the course of three tortuous days, Gillett lost eight successive ballots as the dissidents refused to budge. Facing a deadlock — and the possibility that his opponents might reach across the aisle to elect a Democrat speaker — he yielded, and on the ninth ballot won over 18 of the dissenters, enough to win a third term as speaker.

The victory of the GOP insurgents a century ago didn’t last. In 1924, the Republicans expanded their majority, allowing them to elect a speaker without having to cater to their party’s progressive wing. Gillett was elected to the Senate that year (notably the last time a House speaker won election to the upper chamber). When his successor Nicholas Longworth took over in 1925, he restored his office’s powers and purged from their committee assignments all the dissidents who had rebelled against Gillett.

The lesson endured. After 1925, House speakers of both parties suffered hardly any defections — at least until the second decade of the 21st century. In 2013, 12 Republicans voted against then-speaker John Boehner, who stared them down. In 2015, their number swelled to 24; later that year, Boehner resigned rather than face a likely vote to “vacate the chair.” His successor Paul Ryan won his bid to replace Boehner as a compromise candidate, but, increasingly challenged in a job for which he was ill-suited, announced his intention to step down months before the GOP lost its House majority in the 2018 midterms.

Nancy Pelosi won her party’s unanimous support when she first became speaker in 2007, but only narrowly returned to the job when the Democrats reclaimed the majority in 2019. In that vote, 15 House Democrats refused to support her, with other skeptics swayed only by her promise to step down after the 2022 midterm elections, regardless of the results.

Pelosi is on her way out, but the lessons of history are baleful for both sides of the Republican divide. If the Republican holdouts make a deal with McCarthy — which reports suggest is likely — he or a likeminded successor could turn on them in any future Congress with a larger Republican majority, just as Longworth did within two years of replacing Gillett. In that case, any concessions McCarthy makes now could easily be withdrawn, and the members who extracted them dispatched into the political wilderness.

Alternately, McCarthy could make a deal with Democrats to secure his election. This would effectively surrender the GOP’s hard-won majority to a de facto coalition government that would frustrate the agenda on which McCarthy has adamantly staked his leadership. After a brief, shining moment as little more than a figurehead speaker, he, too, would likely face oblivion at the hands of an outraged Republican base that might well purge the moderates who control the GOP’s establishment wing.

There is no limit to the possible number of votes the House can take. If the GOP has any concern for its credibility, it must advance a candidate who can win as quickly as possible. Signs suggest it is not Kevin McCarthy.