Last week, British Columbia became the first province in Canada and the second jurisdiction in North America to decriminalize the possession of small amounts of hard drugs for personal use. Those drugs include heroin, cocaine, methamphetamine, and even fentanyl, a synthetic opioid more than 50 times more powerful than heroin.

British Columbia follows Oregon, which decriminalized all drugs in 2020, taking a more proactive — if controversial — approach to address the alarming number of overdose deaths across the region. Under the state’s new guidelines, adults 18 years and older caught with less than 2.5 grams of an illicit substance will not be arrested or charged with a criminal offense. Rather, they will be offered information on local treatment and recovery services, if requested, and permitted to keep the drugs.

British Columbia has among the highest drug overdose rates in the world. According to the British Columbia Coroner’s Service, more than 2,300 people died from drug overdoses in the province in 2021, a nearly 30 percent increase from the year before and the highest number on record. The rate of overdose deaths in British Columbia reached 41.7 per 100,000 people last year, compared to 28.3 per 100,000 in the US (although some hard-hit areas such as West Virginia have seen rates as high as 81.3 per 100,000).

Proponents claim decriminalization will help change the perception of substance use from a criminal justice issue to a public health issue. They say it will significantly reduce racial disparities in health care and incarceration, which have inordinately impacted people of color and those from lower socio-economic backgrounds.

These are laudable goals. For far too long, substance use has been viewed strictly through a law enforcement lens, and sadly it’s taken many thousands of deaths for policymakers to embrace other elements of drug policy such as prevention, harm reduction, and treatment. Substance use disorder is a disease like any other, not a moral failing, and no one should have their life forever altered by an arrest for simple drug possession.

But law enforcement still has an important role to play in combatting drugs. And by decriminalizing these substances, authorities may be inadvertently casting aside some important tools.

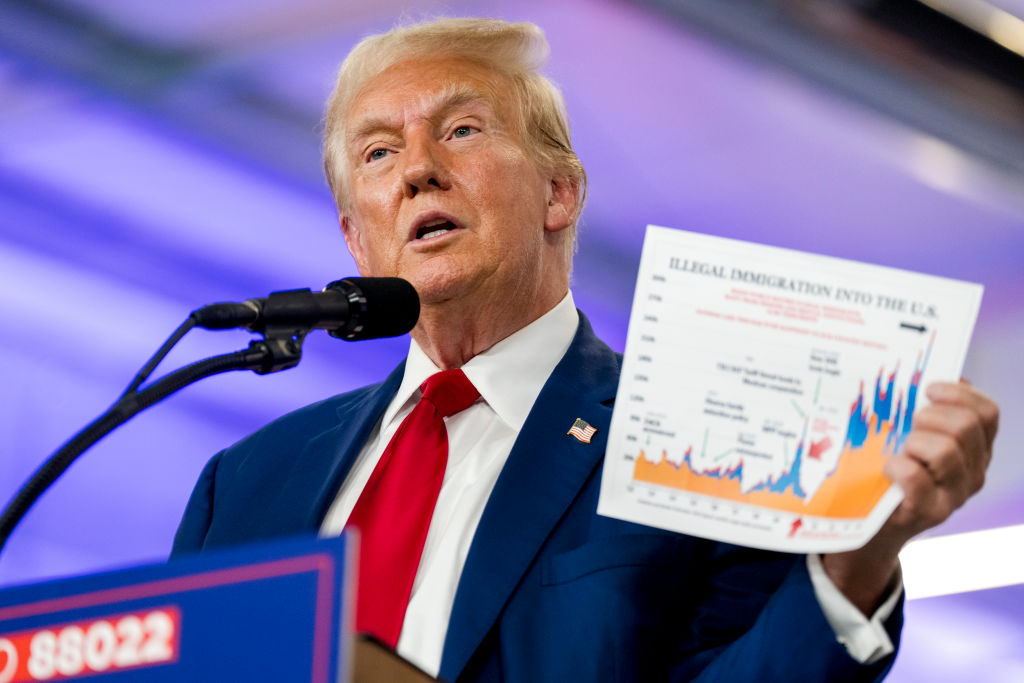

In the first place, decriminalization does not eliminate the broader illicit drug economy — in fact, it is likely to grow without a deterrent. While it’s too soon to draw any firm conclusions from Oregon’s experiment with decriminalization, the initial indicators are concerning. Oregon’s black market remains vibrant, overdose deaths have continued to rise sharply, and drug users from around the country increasingly consider the state a safe haven. British Columbia, too, risks becoming a destination for drug users, as well as traffickers looking for a reliable customer base.

The threat of arrest and imprisonment can serve as a forcing function for those in need of a sometimes-not-so-gentle nudge towards treatment programs. In many cases, drug users require an intervention to help steer them towards treatment and recovery services. Drug courts and diversion programs have long provided an important pathway to treatment that drug users would be unlikely to take without the specter of punishment. British Columbia’s new law provides carrots without the sticks.

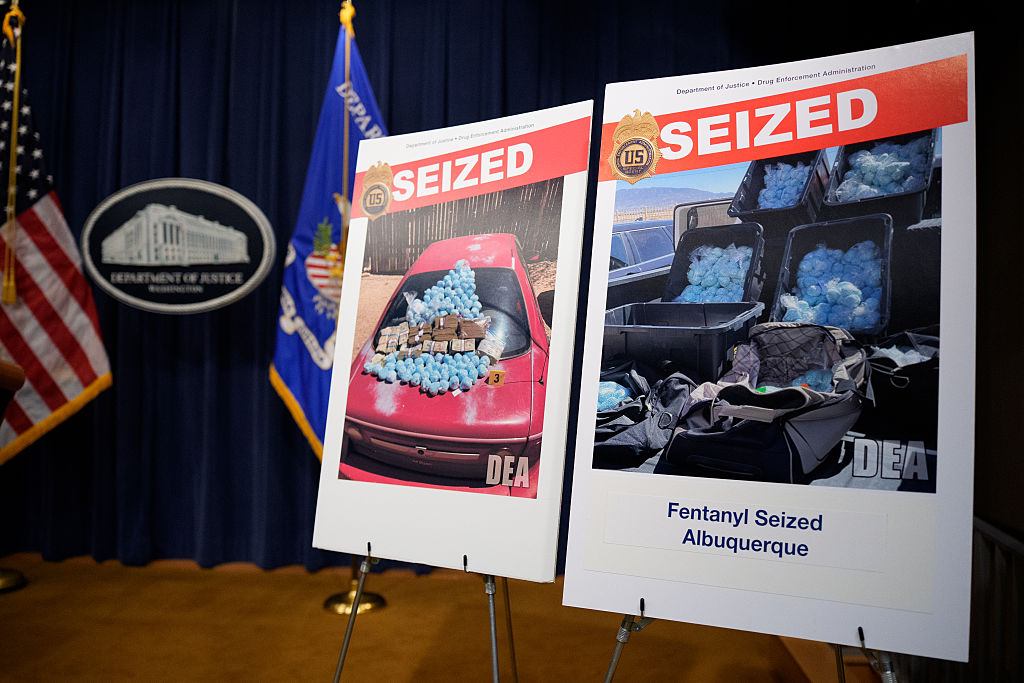

And while British Columbia wisely established guardrails for this new policy — the sale of drugs remains illegal, for example, and the pilot program is set to expire after three years unless it is repealed or replaced — there is also a question of whether now is the time to decriminalize all illicit substances. Illicitly manufactured fentanyl, a drug so potent only two milligrams can be lethal, has thoroughly permeated the drug supply in Canada and the US. The overwhelming majority of drug overdoses are now attributed to fentanyl, and the thought that someone could carry enough to potentially kill 1,250 people without penalty is worrisome.

Just as American states have served as “laboratories of democracy,” so too is British Columbia’s experiment with drug decriminalization. Time will tell whether this approach is the right one, but it’s certainly fraught with risk.

Jim Crotty is the former Deputy Chief of Staff at the US Drug Enforcement Administration