The liberation of Syria’s notorious Sednaya jail close to Damascus a week ago has resulted in a wave of belated outrage in much western media toward the former dictator and his methods. For Syria watchers, there is something rather surreal about this late discovery of the methods of Assad’s regime.

Some of the precise numbers remain disputed. There is, as yet, no independent verification of the statement by Mouaz Mustafa, head of the Syrian Emergency Task Force, that the mass grave at al-Qutayfah contains the remains of at least 100,000 people. The task of piecing together the precise dimensions of the Assad regime’s crimes against the Syrian people, and crucially the names and whereabouts of the victims, is only now beginning. And yet, the fact that this regime was a monstrous one, engaged in the mass slaughter of Syrian civilians, was known to both policymakers and publics in the West.

The facts were in plain sight. A huge body of research and eyewitness testimony has long been available. But there was no widespread public revulsion against Assad in the West. The dictator was not a welcome guest in western capitals at the time of his toppling, but from 2020 until his fall there was little public concern about his rule over Syria. BBC journalist John Simpson said that Assad was “weak, rather than wicked.” The widespread criticism of Simpson may best be attributed to a sort of collective amnesia, of the “Oceania is at war with Eurasia, Oceania has always been at war with Eurasia” variety. Simpson’s error was that he was too slow to realize that the terms of discussion regarding Assad had changed.

The notion proclaimed by western governments that the world is ruled by ‘international law’ is a myth

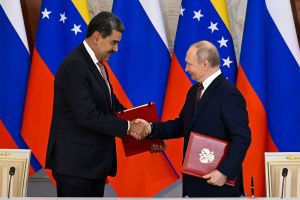

In fact, until HTS’s march on Damascus, 2024 had been a rather good year for Assad. The Italian government was pioneering the normalization of relations with the regime. Italy, in late September 2024, appointed a new ambassador to Damascus. Rome’s initiative to restore ties to Assad’s Syria was supported by seven other European countries.

The Syrian dictator’s rapprochement with the Arab world, meanwhile, was already well underway, pioneered by the United Arab Emirates. Assad’s Syria had been readmitted to the Arab League in May 2023. There was even a behind-the-scenes initiative supported by some influential Israelis which sought to incentivize Assad so that he might act to reduce or end the Iranian presence in the country.

There were good, pragmatic reasons for all these initiatives. Prime Minister Meloni and other European leaders sought to clear the way for the return of Syrian migrants from Europe. Arab leaders were concerned at the emergence of Syria as a narco-state, and wanted to enable the Syrian leader to obtain other sources of income. Israel hoped that Assad would be able to lever the Iranians out of the country — that was always unrealistic.

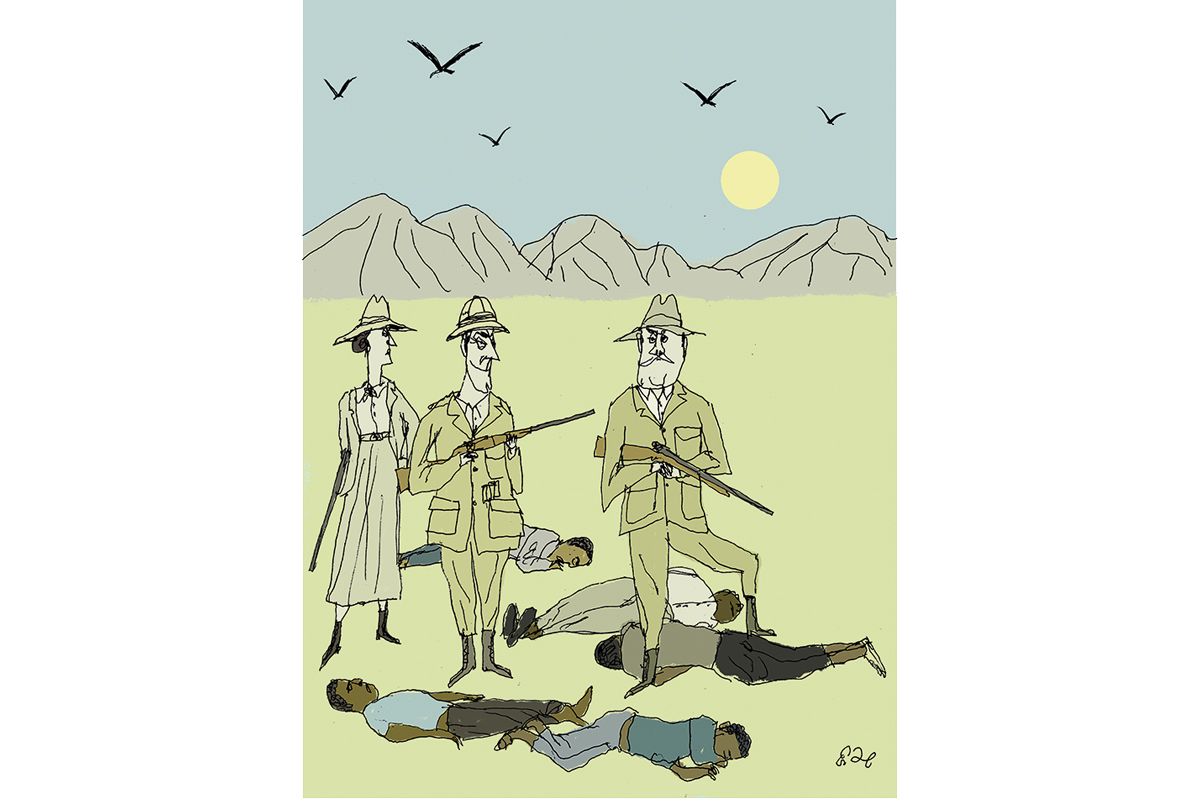

No one should pretend that the facts are only just now becoming available. Among many other examples, a 2017 Amnesty International report aptly entitled “Human Slaughterhouse” describes in close detail the Syrian regime’s policy of mass hangings of arrestees at Sednaya. At that time, the organization reported that 13,000 people had been hanged at the facility.

Sam Dagher, in his seminal Assad or We Burn the Country, perhaps the best single account of the methods used by the regime to remain in power, describes in detail the process of the mass hangings. I remember from it in particular the fact that the regime maintained a room with several sets of gallows in it, one next to another, to streamline the killing process. The efforts by the military defector “Caesar” to smuggle photographs of murdered detainees to Human Rights Watch in 2014/15 offered further incontrovertible proof of what was happening in Assad’s jails.

All those who reported the Syrian war have a bank of evidence of their own, sometimes obtained involuntarily. I remember being in the basement of the Dar al-Shifa hospital in eastern Aleppo city in August 2012, as the hospital was targeted by Assad’s air force. The people there were all civilians, with no air defense, utterly helpless against the murderous intentions of their own government. I wrote the story at the time, and hundreds of similar accounts were published by colleagues. None of it succeeded in shifting the policy dial a single notch. The hospital was destroyed by aerial bombing a couple of months later.

All of which is to say, simply, that claims of “we didn’t know” are false. The evidence has been out there for years, in plain view.

What should be concluded from all this? Nothing particularly profound. That the notion proclaimed by western governments that the world is ruled by something called “international law” is a myth, usually a self-serving one when evoked. That the idea of an “international community” is also a fiction, made more nauseating by how badly that “community” let down the people killed in Sednaya.

Sednaya and the Assad regime’s practices were not particularly aberrant, in the context of the recent history of Syria (and Iraq… and Lebanon). Bashar, who was indeed a “weak” man as John Simpson described him, didn’t invent any of these practices. His father and his father’s predecessors used similar methods. His fellow Ba’athist Saddam Hussein (and his successors) used and use them in Iraq. Indeed, there is ample evidence to suggest that Bashar’s own successors, now busily being normalised by the same people who three weeks ago wanted good relations with the deposed dictator, follow similar practices themselves.

In April 2022, in cooperation with Syrian colleagues, I wrote an article called “Erdoğan’s Secret Prisons in Syria.” The article was based on a 140-page report titled “Sednaya of the North” produced by Syrian activists and based on eyewitness testimony. The report details the random detention and widespread torture (including sexual abuse) of civilians in northern Syria by Turkey-supported militias, the same militias now allied with the new ruling authorities in Damascus. All of which proves, in the immortal French adage, that the more things change, the more they stay the same.

Leave a Reply