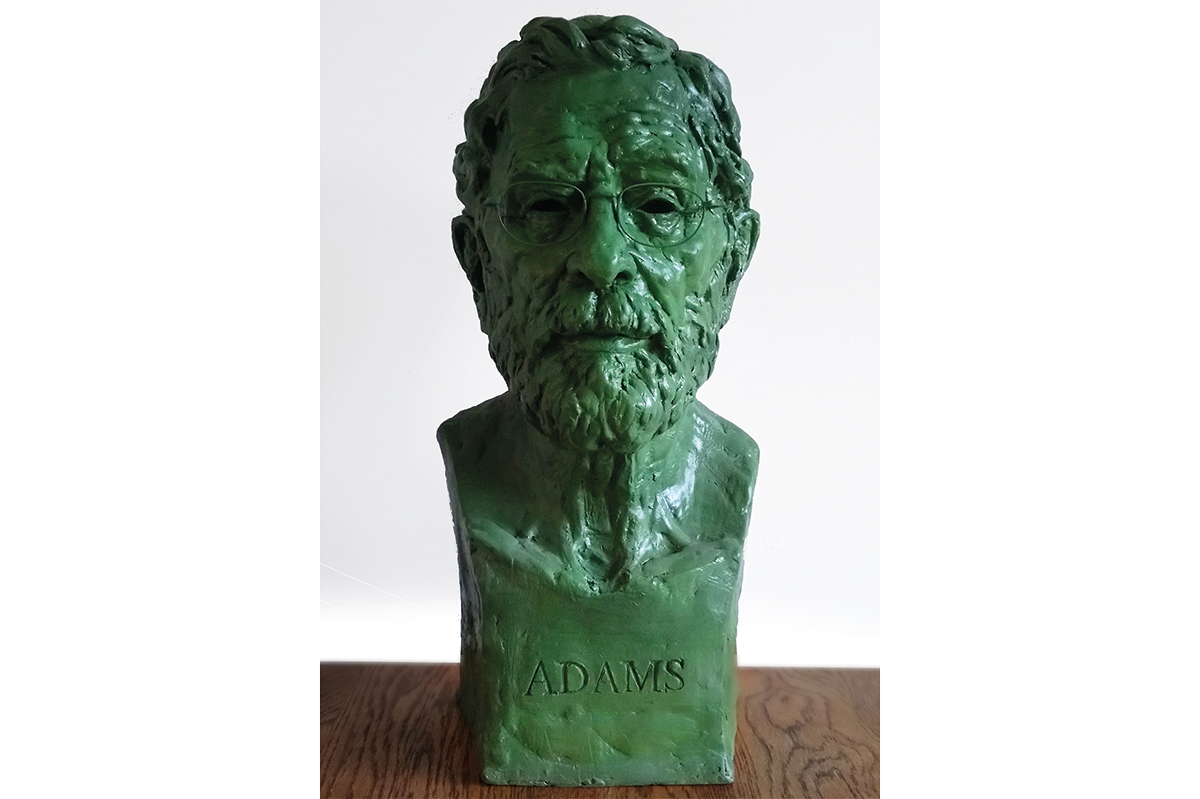

Leo Varadkar’s abrupt resignation Wednesday left even his closest allies perplexed. “I was very surprised, I didn’t expect it at all,” said his deputy, Micheal Martin, after the announcement. Varadkar said he’s stepping down for reasons that were “both personal and political,” to give Fine Gael the best chance of victory. So what made him walk?

Varadkar’s government rebuffed people’s concerns with platitudes

Varadkar may have thought he was continuing a decades-long progressive trend where liberal Irish governments had the wind at their backs. Divorce and same-sex marriage were legalized after successful referendums, and most recently, a ban on abortions was repealed. Ireland was shedding the small-c conservative, Roman Catholic principles on which it was founded. And at an astonishing speed.

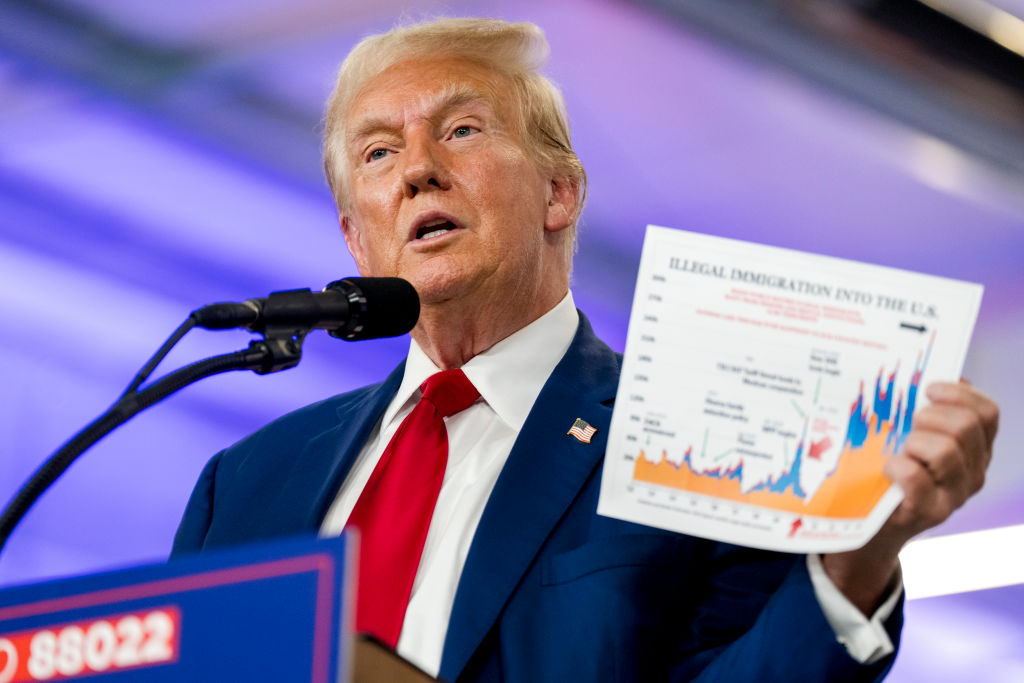

But like a gambler unable to quit while he’s ahead, Varadkar — already on shaky electoral ground over his experiment with open borders — pushed the chips back in for another spin of the wheel by calling a double referendum to “modernize” Ireland’s constitution with two amendments. The first was to remove a reference to marriage being the bedrock of the family, the second proposed deleting a reference to the importance of the “mother’s duties in the home.” He had pitched the referendums as a chance to delete some “very old-fashioned, very sexist language about women” from the constitution, and urged the Irish public to not take a “step backwards” by voting No.

By framing the vote in this way — the past versus the future — Varadkar was going for broke. The implication was that if it failed to pass, the Irish people are sexist old fogeys. The unwisdom of this became apparent as the ballots poured in to show both proposals were resoundingly defeated (one by 74 percent) in one of the most conclusive referendum results in Irish history. Varadkar was forced to admit voters had given his government “two wallops.” With a third one waiting, he imagined, if he stood for re-election.

Polls had suggested a “Yes-Yes” vote — supported by all the major parties — would pass with ease. But Varadkar, who was out canvassing in the well-heeled parts of Dublin ahead of the vote, misjudged the mood in the rest of the country — with every county outside of the capital voting No.

The result was ill-timed for a government already on the ropes over mass migration and housing and services shortages. Varadkar’s government appeared out of touch — indulging in impractical progressive crusades while bungling on the most pressing concerns of ordinary Irish citizens.

So the referendum double whammy is part of a wider theme of Varadkar’s loosening of Ireland’s borders, leading its population to swell by almost two percent last year despite a majority of voters in favor of tighter border controls. A glut of asylum seekers were bussed to hotels and other spaces around the country, often at night and without warning to local communities, leaving small towns across rural Ireland unrecognizable.

Varadkar’s government rebuffed people’s concerns with platitudes appealing to Ireland’s “compassion” and wooden language about its “international obligations.” This catapulted immigration from a fringe concern to the number one issue in Irish politics, and converted a once compliant Irish public into reflexive skeptics.

The dam looked as if it was about to burst yesterday as ten members of Varadkar’s Fine Gael Party announced they would not run in the next election. Losing political capital, as Ernest Hemingway wrote of going bankrupt, happens “gradually and then suddenly.” For the progressives of Fine Gael, things have just moved very suddenly indeed.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.

Leave a Reply