A friend makes maps, colorful graphic maps of mostly Washington, DC neighborhoods. She sells them, often framed, by the bushel at farmer’s markets and through her own shop. She often asks people where they live, but never how they live. Her service — the map — is neutral regarding whom one is married to, what religion they practice, which political party they support. Everyone is welcome to buy a map, and all the maps are the same.

Not so for the hypothetical wedding cake maker in the next stall. While anyone is free (indeed, allowed by law) to buy an off-the-rack cake, she refuses to use her form of speech to support LGBTQ weddings. She’ll sell a gay couple a cake reading “Have a Great Day” but will not create a rainbow design with two women holding hands. She claims that violates both her First Amendment right to practice her religion and, the emphasis here, her 1A right to free speech. Anti-discrimination laws (20 states have laws specifically protecting LGBTQ people) cannot compel her to create speech she does not believe in.

There’s a lot going on under the surface at the farmer’s market, and that’s why the Supreme Court has had to step in and sort things out.

The case before them is 303 Creative v. Elenis. It’s ostensibly a religious 1A challenge but it only incidentally concerns religion while really asking the question of “what is speech” and when can anti-discrimination laws compel it. Specifically, “whether applying a public-accommodation law to compel an artist to speak or stay silent violates the free speech clause of the First Amendment.” The Court heard oral arguments in early December, with a decision due in June.

The story starts familiarly enough for 2022: Lorie Smith is a Colorado website designer who, according to her Supreme Court brief, intends to design custom wedding websites, and refuses to design websites that advance ideas or causes she opposes, such as same-sex marriage. She says she will work with gay clients on other, non-same-sex-marriage websites.

The existing law is pretty straightforward: if a vendor is providing a service such as, say, running a drug store sandwich counter, then it doesn’t enjoy a constitutional right to refuse service to customers on the basis of status or identity. But though the state can demand that businesses provide goods and services to all customers without regard to race, sex, sexual orientation, and other protected categories, it cannot demand that businesses or individuals engage in speech proclaiming messages they oppose. Smith argues designing websites is a form of speech.

The essence of the 1A is that the government cannot compel speech. Compelled speech crushes the speaker’s conscience and is a tool of authoritarianism. In Justice Samuel Alito’s words, a win for the state of Colorado against Smith would mean some businesses that provide custom speech for customers could be forced to “espouse things they loathe.”

The mother of all cannot-compel-speech cases is 1943’s West Virginia Board of Education v. Barnette. At the height of World War II, the Supreme Court held that West Virginia could not make Jehovah’s Witness students salute and pledge allegiance to the American flag. The decision contained arguably the most famous single sentence in American First Amendment jurisprudence: “If there is any fixed star in our constitutional constellation, it is that no official, high or petty, can prescribe what shall be orthodox in politics, nationalism, religion, or other matters of opinion, or force citizens to confess by word or act their faith therein.” The key question in 303 Creative is whether Smith is denying a service (websites) on the basis of status (her customers are gay) or refusing to engage in speech because she disagreed with its message.

In this case, the Supreme Court was well aware of a similar one, Masterpiece Cakeshop v. Colorado Civil Rights Commission, that never resolved the underlying core issue of what is speech, floundering instead on the religious angle and even the question of whether certain cake makers held a monopoly for their services. So never mind.

In the oral arguments just heard in 303 Creative, the Supreme Court’s conservative majority seemed prepared to rule that a designer has a First Amendment right to refuse to create websites celebrating same-sex weddings based on her Christian faith despite a state law that forbids discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation. But several justices leaning in that direction also appeared to be searching for limiting principles so as not to unintentionally upend all sorts of anti-discrimination laws.

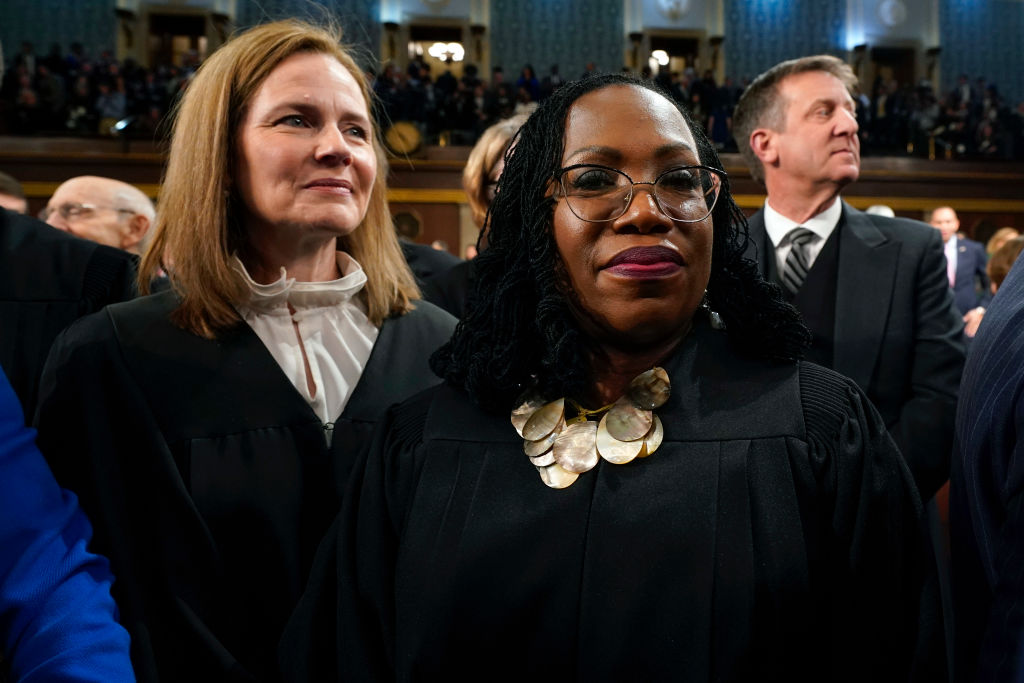

The justices seemed to be creating new ground legally separating racists from those who oppose gay marriage. Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson brought up a hypothetical mall Santa, wondering whether a photographer who wanted to create the aesthetic of the movie It’s a Wonderful Life might be able to exclude black children. Alito countered by conjuring up a black Santa at the other end of the mall who wanted to be free to refuse a photograph to a child wearing a Ku Klux Klan outfit.

The difference between a service (a sandwich at a lunch counter) and art (words expressing joy over a same-sex union) came up repeatedly. A thread throughout the arguments was whether the refusal to provide wedding-related services for a same-sex couple could be compared to the same treatment of interracial couples. The lawyer for 303 Creative said it could not and pointed out that in its decision finding a constitutional right to marriage for gay couples, the Court noted that respect was due to those who disagreed with same-sex marriage as a matter of religious belief. No such call for respect exists for those who oppose interracial marriage.

The arguments explored the difference between businesses engaged in expression and ones simply selling goods; the difference between a client’s message and that of the designer; the difference between discrimination against gay couples and compelling the creation of messages supporting same-sex marriage; and the difference between discrimination based on race and that based on sexual orientation. Whereas the earlier Masterpiece Cakeshop case failed to yield a definitive ruling, this one is expected to settle the question of whether businesses open to the public and engaged in expression can refuse to provide services to potential customers based on their religious or other convictions.

What it all means: if the Court acts as it has signaled it will, in favor of 303 Creative, then this will free conservative creative people to work within their fields without having to express beliefs, such as acceptance of same-sex marriage, contrary to their conscience. Though the Court will also preserve anti-discrimination laws, hard won, to ensure we do not slip backwards to a time of segregated lunch counters and the like.