The American Spectator Foundation has complained that its trademark is being infringed by The Spectator in the United States.

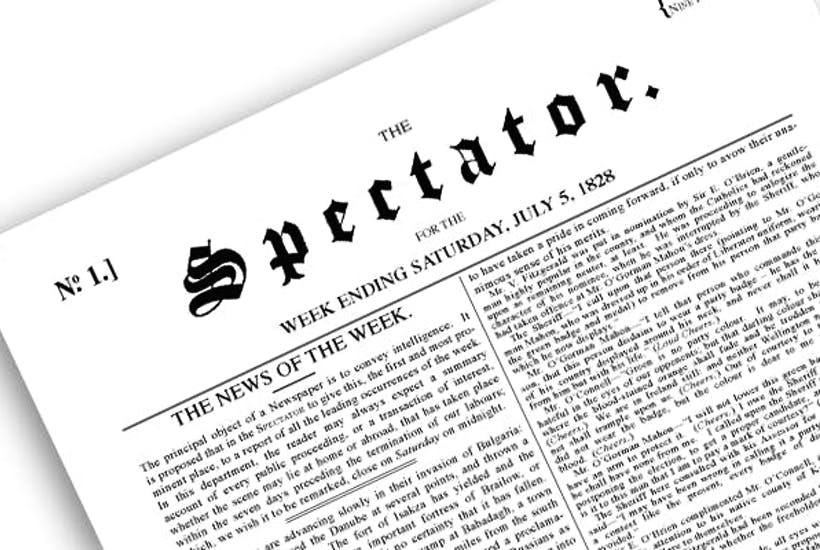

The Spectator is the oldest magazine in the world: founded in 1828 and read in America since at least the middle of the 19th century when, alone among influential British publications, it supported the North and the anti-slavery movement in the American Civil War. It has been sold in the US under that name continuously since that time.

The American Spectator, previously called the Alternative, was founded in 1967, very much a publishing newcomer compared with The Spectator. It was not the first US publication to refer to The Spectator in its name. Indeed, an earlier journal, also called the American Spectator, was founded in 1932. This earlier version also styled itself as an American version of The Spectator. As the 1945 Current Biography entry for its founder G.J. Nathan puts it: ‘Nathan with Theodore Dreiser, Eugene O’Neill, James Branch Cabell and Ernest Boyd founded the American Spectator, a “literary newspaper” patterned after the London Spectator.’ Moreover, a number of other American publications have used the word ‘Spectator’ in their name, including, among others, the Washington Spectator, the Columbia Daily Spectator, the Wine Spectator and the Spectator Index.

Like many publications of similar stature, The Spectator produces various editions around the world with content tailored to different markets. In March 2018, The Spectator launched a website that placed particular emphasis on the US, with more American content coupled with UK and global output generated largely from London. Encouraged by the site’s success, we decided to publish a monthly print ‘US edition’. Like the online iteration, it combines original US content with UK and global content, covering current affairs and culture. We launched the US edition in October 2019.

Until this lawsuit, The Spectator had a friendly relationship with the American Spectator and its founding editor, Robert Emmett Tyrrell Jr, who clearly aped The Spectator’s layout, masthead and editorial style when he changed the name of his magazine from the Alternative to the Alternative: The American Spectator in 1967, and about a decade later to just the American Spectator.

We’d always wished Mr Tyrrell’s American Spectator well and had discussed our plans in America with him and others at the foundation in advance of our US launch.

The Spectator and the American Spectator (and many other publications that use the word ‘Spectator’ in their masthead) have co-existed for many decades without issue. The Spectator today is a very different magazine to the American Spectator. The Spectator has by its nature a much more international outlook, believes in diversity of opinion and covers culture, books and the arts from a range of perspectives. The American Spectator is more ideological and narrowly focused on the politics of the American right. So we have always operated on the basis that there should be room for both of us and more in the marketplace.

Given our longstanding presence in America and that amicable relationship, we were surprised when the American Spectator decided to pursue us through the courts.

The Spectator was owned by Americans in the 1860s. The Spectator almost bankrupted itself supporting the North in the Civil War. In 1901 President Teddy Roosevelt, an avid reader, invited the then editor of The Spectator to stay in the White House. The Spectator also helped facilitate briefings for American officials and journalists during World War One. And all the while, The Spectator has covered US politics and culture alongside UK and global matters, no differently than it does today.

Andrew Neil, chairman of The Spectator, says: ‘The American Spectator seems to believe it has dominion over the word “spectator” in the United States. Given our distinguished history in Britain and America, our worldwide fame as The Spectator magazine — the oldest in the world — and the prevalence of other magazines with “spectator” in their titles, we find that claim not only wrong but absurd.’