By disposition, conservatives distrust government. They are for “limited government” and worry about the coercive power of the state intruding upon individual liberty. But these days, some conservatives tell us that, when they finally get their hands on the levers of power, they will be energetic in exercising them to achieve their (presumably conservative) ends. Is that a contradiction or indication of hypocrisy? Maybe. Or maybe it is just a sign of how deeply anti-conservative sentiment has burrowed into the tissues of our society.

No doubt I would prefer the policies promulgated by a conservative administration to the policies we are saddled with now. But my low opinion of human nature inclines me to distrust government power no matter who is in charge.

Ronald Reagan is out of fashion these days, but I think he was right when he observed that “democracy is less a system of government than it is a system to keep government limited, unintrusive: a system of constraints on power to keep politics and government secondary to the important things in life, the true sources of value found only in family and faith.”

Whether what Reagan says is true of democracy itself is something that we might, with Tocqueville, and with sadness, want to question. Too often democracy has been prey to deformations that encourage rather than retard the growth of government. That indeed was part of what the founders had to wrangle/contend with as they combed through the graveyard of history’s failed republics in their efforts to frame a more robust system of government.

There is, I acknowledge, an inescapable irony. The founders, to be sure, were deeply concerned to protect individual and states’ rights against the prerogatives of the federal government. For example, James Madison, in Federalist 45, explicitly declared that the powers delegated by the Constitution to the federal government were “few and defined,” having to do mostly with “external objects” like war, peace and foreign commerce. The powers delegated to the individual states, on the other hand, were “numerous and indefinite,” extending, said Madison, to “all the objects which, in the ordinary course of affairs, concern the lives, liberties, and properties of the people, and the internal order, improvement, and prosperity of the State.” That is a prescription for the division of power we would do well to resuscitate.

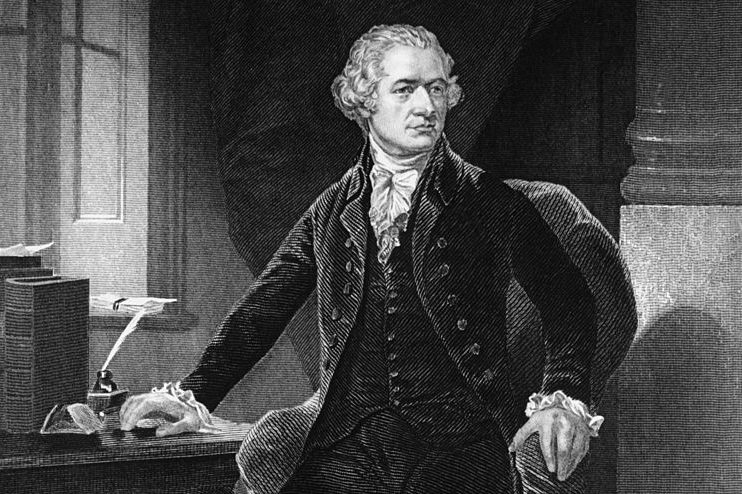

Still, it is worth acknowledging that the Founders, although deeply concerned with limiting the sphere of government power, were also concerned with forging a strong and efficient federal government. The Federalist Papers, after all, took aim at the abundant anti-Federalist commentary that opposed the proposed Constitution precisely because, so thought the anti-Federalists, it arrogated too much power to a central authority. But just this, the Founders argued, was the price of creating and maintaining that “more perfect union” of which the Constitution speaks. “The vigour of government,” Alexander Hamilton wrote in the very first of the Federalist papers, “is essential to the security of liberty.” The goal, he put it later, is “a happy mean” which combines “the energy of government with the security of private rights.”

So much for acknowledging the requirements of “the vigour of government.” I promise not to say another word in its favor. For our problem today is not to assure the “energy of government,” but quite the opposite: to redress the balance and to reestablish that “happy mean” Hamilton spoke of by asserting the legitimate jurisdiction of private rights against a rampant and engorging bureaucratic Leviathan.

Roger Kimball is the editor and publisher of the New Criterion, publisher of Encounter Books and a Spectator columnist and contributing editor. This article is one excerpt from “Fight for the right,” a symposium on the future of American conservatism. Read the full series here.