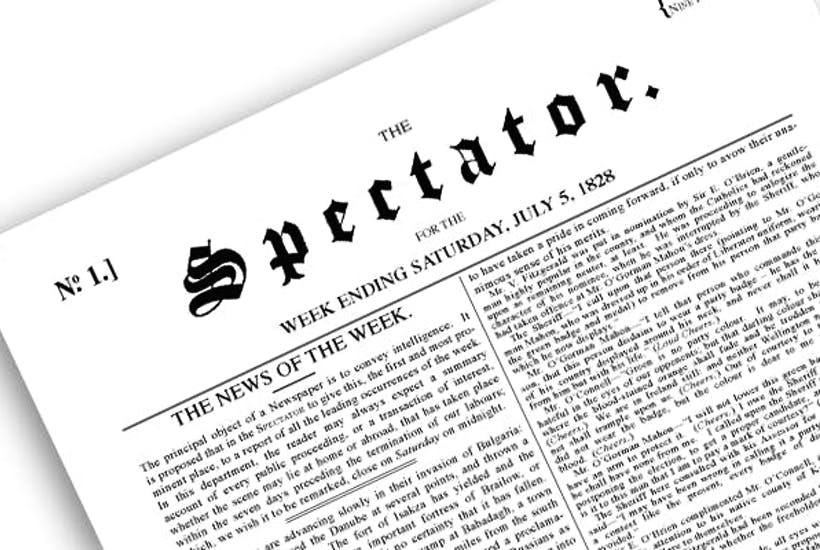

After a year-long auction drama that involved sheikhs and moguls and even ended up changing British law, The Spectator has a new owner. The financier Sir Paul Marshall is to become the magazine’s fourteenth proprietor.

Had The Spectator been sold to the Emirati government, as was on the cards, we would have faced obvious questions about our operational and editorial independence. That will be protected under Sir Paul, who is buying The Spectator because he admires what we have achieved, believes in the magazine’s values and, most importantly, knows that we can go further with more investment.

The price we’ve been sold for, £100 million ($131 million), speaks to that belief in our potential. We were valued at £20 million when we separated from the Daily Telegraph in 2005. Since then, the magazine market has fallen by about two-thirds but our subscriptions have more than doubled. This five times valuation increase is, to put it mildly, rare in our industry. The auction attracted twenty-two potential bidders, including some of the greatest and most respected names in British and European publishing. Not bad for a publication with barely three dozen journalists.

This deal is vindication of The Spectator’s unusual business model. In this trade, there is always pressure to go for the digital “quick wins” (clickbait articles, advertorials, etc.) but we rejected this as a false economy — so commercial that it’s uncommercial. It would take us downmarket, deform our character and, ergo, reduce the company’s value. So we went the other way, using our success to double down on the magazine’s finest traditions in the belief that quality of writing matters above all. We did a lot that went against the conventional digital wisdom. We put together a different business model and a unique way of working, based on close collaboration between all departments and journalists equally comfortable with print, digital and broadcast.

When other publications were shedding sub-editors, we poached the best ones we could find. When newspapers shrank their books sections, we proudly kept Sam Leith’s at ten-plus pages and gave him a podcast. We created a research team who apply perhaps the most robust pre-publication scrutiny on Fleet Street (mindful that it matters more than ever that readers can trust the facts they read). When other weeklies started cutting costs by not printing over Easter and the summer, we put more effort than ever into the issues released in those holiday periods.

The digital temptations that can lure publications to their grave (“The world has changed! Look at the clicks! Drop the opera review!”) are dangerous as they come dripping in what looks like supportive data. You can end up not just being edited by algorithm but stripping a publication of nuance, variety and soul. Our belief was that if we innovated, and used the proceeds to double or treble down on what makes The Spectator different, we would maximize the value of the company as well as serve our readers. Much of what we did could be seen as uneconomic on an individual basis — but put it all together and you get a five times valuation uplift.

Andrew Neil, the author of our business strategy, announced some time ago that he will be stepping down when the deal completes. Having the company run by a journalist of his stature made everything possible. He handled the Barclay family and served as a firewall, running the business side while protecting the editor’s freedom. That included freedom from him: the most he asked of me, in all these years, was to enquire what we were running on the cover. When I needed advice, especially for the trickiest problems, he was always there. When battles come — as they always do in journalism — there is no one you’d rather have on your side. When advertisers complained about writers, he banned the advertisers. My own debt to him is greater than I can say here.

This deal also ends the custodianship of the Barclay family, to whom I’d like to pay tribute. They found us a glorious home in 22 Old Queen Street, believing we needed our own building to develop our own culture. But they almost never visited it, not even to attend parties. The distance was strategic: they wanted this to be our show and to avoid any hint of editorial interference. Only once did they ask to discuss the magazine with me, wanting to be told in advance what side we’d take on Brexit (they gave no clue as to what they’d like the answer to be). As editor I was not given a single proprietorial suggestion, let alone instruction. This laissez-faire approach did what they intended. The Spectator behaved like a startup — and grew like one.

The takeover drama established, through Parliament, the principle that autocratic governments should not own national publications. But perhaps the most important point made by the deal is that the real value of publications cannot be determined by sales numbers, clicks or digital KPIs, although all play a part. Our former assistant editor, the novelist John Buchan, summed this up in 1928. I’d like to give the last word to him.

It is fatal to keep your ear only to the ground, to speak only smooth things, to give your readers only what you think they will like. That way temporary popularity may lie, but not enduring popularity. To win an audience, tact and good sense are required: and to keep it, integrity and courage. The Spectator has had a unique influence amongst our countrymen – an influence won by no catchpenny arts, but by moral and intellectual candour. Esto perpetua.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.

Leave a Reply