When future historians chronicle the period after the Cold War, the rise of China will dominate their accounts. Beginning in the 2000s, China unleashed a flood of state-sponsored manufactures, many of them produced by western multinational corporations using Chinese labor on Chinese soil. This impoverished much of the already pressured industrial working class in the US and Europe, triggering populist revolts in rustbelts like the American Midwest, the north of England and eastern Germany.

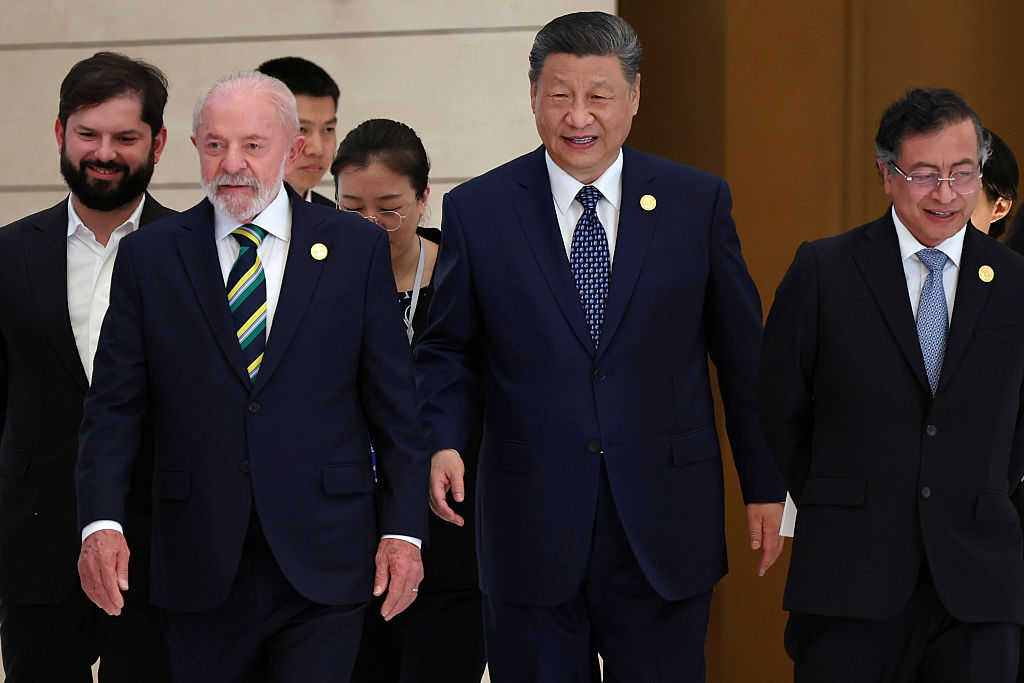

The recycling of profits from China’s chronic trade surpluses through the global financial system enriched western financial interests and helped to inflate bubbles in the real estate and stock markets. These burst in 2008, causing the Great Recession. Meanwhile, Chinese military assertiveness in the South China Sea and along the Sino-Indian border has produced a regional arms race in Asia. China’s aggressive ‘wolf-warrior diplomacy’ has undercut its Belt and Road Initiative, provoking a backlash from Asia to Europe. At the same time, the reassertion of Leninist tyranny under Xi Jinping has turned China into a high-tech totalitarian state, with a nightmarish social-credit surveillance system, the destruction of limited liberty in Hong Kong and the horrifying repression of China’s Uighur minority.

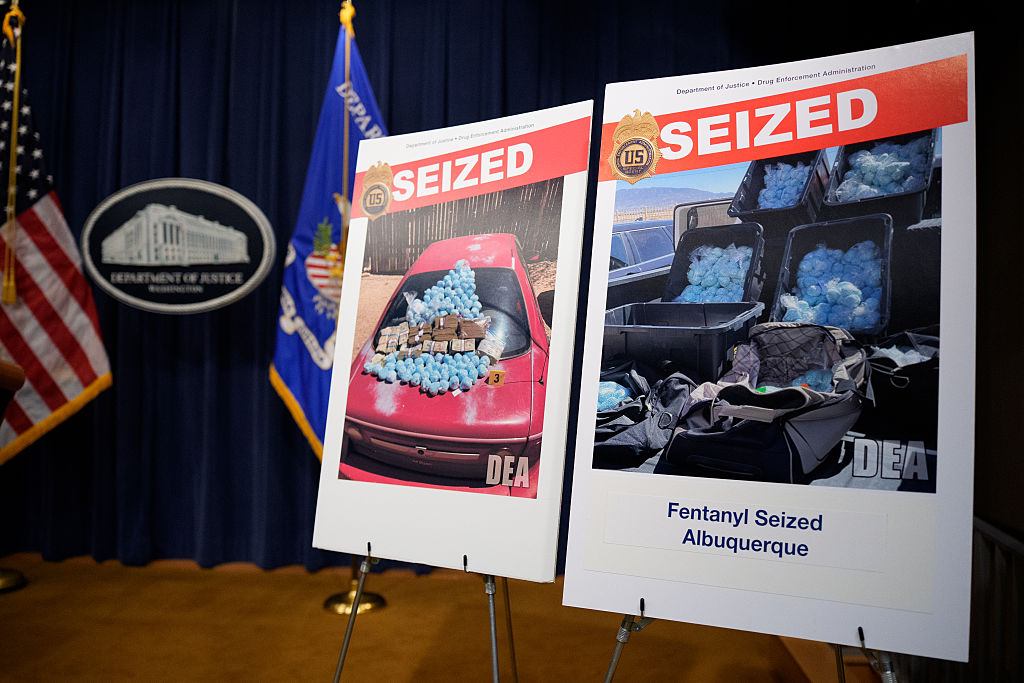

On top of this, an unusually deadly coronavirus escaped from China in early 2020. It caused the worst global pandemic since the Spanish flu of 1918 and the worst global economic crisis since the Great Depression of the 1930s. It also forced the rest of the world to acknowledge that its supplies of medical equipment and drugs depended on factories in dictatorial China.

It is as though a medium-sized planet, a Mars or Venus, began to swell in size and mass, destabilizing the orbits of every other planet in its solar system all at once. In the West there are two views of China’s effect on the world order. Liberal globalists define the ‘China problem’ in terms of China’s internal economic policies and government.

In this view, China’s increasing share of global industry, including advanced technology sectors, is not in itself a problem, as long as the Chinese regime abandons its state-capitalist economic policies for free trade and privatization.

In the political realm, abandonment of the dictatorship of the Chinese Communist party, whether for true multiparty democracy or something like the mild semi-liberal authoritarianism of Singapore’s ruling party, might ease tensions and restart the stalled progress of the post-Cold War world toward one big happy global market and universal human rights, if not universal free elections. In this optimistic view, a non-totalitarian China that respects human rights and embraces liberal market globalism might be no more of a threat than contemporary Japan, if Japan had 1.4 billion people.

Realists disagree with liberal globalists. The challenge posed by the new China to US foreign policy and American alliances is not primarily caused by China’s repressive regime or its cheating at trade, bad as those are. In our analogy of the solar system, the challenge arises from Planet China’s ever-increasing gravitational mass.

The ‘liberal world order’ is better described as liberal hegemony. This system, the Pax Americana, was first established by the US and its European and East Asian protectorates during the Cold War, and was partially extended on a global scale after the fall of the Berlin Wall. As the hegemon — ‘leader’ — of the Pax Americana, the United States has provided three major public goods to its allies and clients, with no expectation that they will return the favor: one-way military protection; one-way access to US consumer, financial and asset markets; and the use of the dollar as the world’s reserve currency.

All three of these hegemonic services have come at a significant cost to the American people since 1945. Nearly 100,000 Americans were killed in the Korean and Vietnamese wars, which were fought primarily to reassure America’s major military protectorates, Japan and West Germany, that US commitment to their defense against the communist bloc was credible. In the interest of Cold War alliance unity, the US practiced one-way free trade, turning a blind eye to the Japanese, South Korean and Taiwanese policies of protecting their own national industries while grabbing large shares of the American market. Last but not least, the role of the dollar as the global reserve currency has prevented the US from using devaluation to help its own export industries.

When the US led by large margins in both military power and manufacturing, the costs of hegemony were outweighed by the benefits of preventing Germany, Japan and other allies and clients from drifting into neutrality in the Cold War or re-emerging as independent military powers after 1989. But the rise of China has changed the costs and benefits of America’s grand strategy of liberal hegemony. In terms of purchasing power parity (PPP), which is the most accurate comparative measure, China has already surpassed the EU and the United States and is now the largest economy in the world. To be sure, per capita income in the US and Europe remains much higher than in China. Even so, it makes no sense for the US, the world’s second- or third-largest economy, to continue to absorb disproportionately the costs of providing military protection and economic services to the rest of the world.

Most scenarios predict that the American and European shares of the global economy will continue to shrink, relative to China’s share. In 1945, the US share of global PPP accounted for around half of global GDP. The consulting firm PricewaterhouseCoopers predicts that the US share of global GDP in PPP terms will fall from 16 percent in 2017 to 12 percent in 2050. That would make the US the third-biggest economy after China (20 percent) and India (15 percent). Meanwhile, the EU share of the world economy will shrink from 15 percent in 2017 to 9 percent in 2050. These are only estimates, but the trend is clear and is unlikely to be changed significantly by the COVID-19 pandemic and its economic aftermath.

Manufacturing capacity, not financial rents or intellectual property royalties, is the primary basis of national military strength. In 2010, China displaced the US as the world’s largest manufacturing nation. If we look at strategic industries that are important for the military, the relative decline of the US and its allies is even more striking.

The global civilian drone industry was pioneered in the US, but it is now dominated by a single Chinese company, DJI, which controls more than 70 percent of the global market and nearly 77 percent of the US market. In 2019, China accounted for 45 percent of global commercial shipbuilding, having bypassed America’s allies Japan and South Korea; the US no longer has a significant civilian shipbuilding industry at all. While the US until recently has relied on foreign rockets (including Russian ones) to launch payloads into space, 96 percent of Chinese satellites now in orbit were launched on Chinese-manufactured rockets.

America’s status as ‘the world’s only superpower’ depends on what the scholar Barry Posen calls the ‘command of the commons’: the ability to project military power over large distances through sea, air and space into Europe, Asia and the Middle East — and against enemy opposition. If not only the US’s manufacturing bases but also those of its military allies are eclipsed by the Chinese military-industrial complex, then the US, to use Mao’s mocking term, will be exposed as a ‘paper tiger’.

[special_offer]