Washington DC, 2030

The reasons why the United States and the People’s Republic of China (PRC) avoided total war, let alone a nuclear exchange, during their armed conflict in the autumn of 2025 remain a source of dispute. What is clearer is why the Sino-American Littoral War broke out, and what course it took. The United States lost part of its position in Asia, while China found its gains an unexpected burden. The resulting cold war between the United States and China became the defining feature of geopolitics in the Asia-Pacific in the middle of the 21st century. To understand what happened and why, we must start with the political environment between Washington and Beijing in the years leading up to the war, look at their military assets and assess the balance of power in the western Pacific at the outset of hostilities. Only then will analysts be able to interpret the political and military decisions taken by both sides.

The political background

With the end of the Cold War between the West and the Communist East, American policymakers turned to constructing a new great-power relationship with China despite growing strains between the two countries. Under both Republican and Democratic administrations, Washington steadily attempted to integrate China into what liberal internationalists called the ‘rules-based international order’. While the Clinton and George W. Bush administrations midwifed the PRC’s entrance into the World Trade Organization, successive presidents ignored growing evidence of China’s industrial and cyber espionage against both the US government and private American businesses. It was, however, during the Barack Obama administration that the real seeds of the 2025 Littoral War were sown.

The Obama administration developed the Bush administration’s high-level bilateral talks into a ‘Strategic and Economic Dialogue’ and energetically engaged the Chinese government. Yet serious challenges to Asian regional stability emerged during Obama’s two terms. Most egregiously, Beijing decided to build and fortify islands in disputed maritime territory in the South China Sea. Ownership of various coral reefs and shoals in the Spratly and Paracel island chains had long been contested between China and a host of Southeast Asian countries, many of which had built modest defensive installations on some of their possessions. Yet Beijing claimed that Secretary of State Hillary Clinton’s comments at a regional security meeting in 2010 demonstrated US antagonism toward China’s rightful claims.

Clinton stated that the Obama administration considered the peaceful multilateral resolution of competing territorial claims to be in the national interest. Such statements were combined with calls for a ‘rebalance’ or ‘pivot’ to Asia and assertions by Obama officials that the Asia-Pacific was now America’s key geopolitical focus. To buttress the pivot, the Obama administration pursued a new multilateral free trade agreement, the TransPacific Partnership (TPP). The Pentagon announced it would increase troop deployments and shift maritime assets so that 60 percent of all US naval strength would be in the Asia-Pacific region. In response, Beijing claimed the entire South China Sea as its territorial waters and a ‘core national interest’, and Chinese forces harassed US Navy ships and airplanes on patrol.

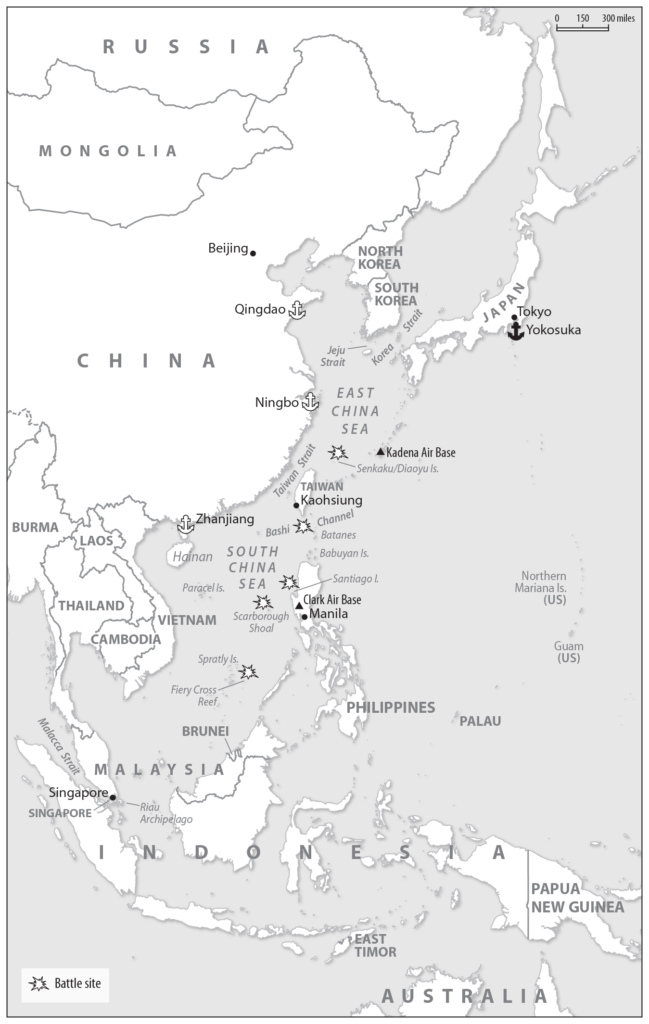

When Washington failed to support Manila during the Scarborough Shoal crisis of mid-2012, China took effective control of the shoal, and Beijing felt assured that American commitments to allies in the South China Sea were hollow. After 2013, the new Chinese president, Xi Jinping, added concrete action to rhetoric, first beginning a major land-reclamation campaign in the Spratlys, and then proceeding to militarize China’s new possessions there as well as some older ones in the Paracels. The Chinese military built three port facilities, each the size of Pearl Harbor. They laid runways capable of handling fighter jets and bombers. They installed radar and anti-ship and antiaircraft weapons. They built barracks and storage facilities.

Placing airfields and weaponry on its purported possessions allowed Beijing to effectively control the heart of the South China Sea, through which as much as 70 percent of global trade passed, and to project power throughout the region. China also launched its first aircraft carrier and conducted military exercises hundreds of miles from its recognized territorial waters, but close to the strategic waterways of other Southeast Asian nations. Its PLA Navy (Plan) ships regularly transited into the Indian Ocean and through strategic straits near Japan into the western Pacific Ocean.

The Obama administration’s response was muddled and hesitant. It initially downplayed the island-building campaign, then condemned it. When Washington belatedly demanded that Beijing cease its actions, Chinese officials darkly warned of war should the United States not stop its pressure campaign. Washington also failed to take advantage of international law in its response to Beijing, even after July 2016, when the Hague’s Permanent Court of Arbitration ruled against Chinese claims in a case brought by the Philippines. Declaring that Beijing could not assert ownership over low-elevation landforms, even if they had been built up, and that China’s historical claims in the South China Sea had no legal standing, the Hague ruling should have been a deterrent. But Beijing simply ignored the court’s ruling, and the Obama administration did nothing to rally regional pressure.

Most crucially, Obama hesitated to conduct military operations in the contested areas. Those could have sent clear signals to Beijing that the United States would not meekly surrender the region to China. It took the administration months to decide to proceed with freedom of navigation operations (Fonops) that would approach China’s new islands at a distance of less than 12 nautical miles (the territorial limit for legitimate possessions). Only four Fonops were conducted during Obama’s last two years in office, and the US Navy muddied the waters by claiming that it was operating under the rules of ‘innocent passage’, which is a different category of transit under international law. Chinese ships and aircraft did not actively interfere with American forces during these operations but did shadow them, issuing repeated warnings to leave the area. The outcome of Obama’s approach was to make the United States appear irresolute and confused about how to blunt China’s advances. This raised further doubts in the minds of Asian allies, especially the Philippines, about whether Washington would live up to its treaty commitments.

Donald Trump became president in 2017 having taken perhaps the hardest line of any presidential candidate toward China. Rejecting prior presidential approaches, Trump explicitly linked trade and security issues, promising to end China’s unfair trading practices and warning that he would challenge Beijing in the South China Sea. After his first few months in office, when it appeared that he would revert to a more traditional posture toward China, Trump levied major tariffs against Chinese goods, ultimately encompassing $550 billion, or nearly all of China’s exports to the United States. At the same time, he increased military spending and authorized more Fonops and aerial overflights in the South China Sea, eventually increasing them to approximately one every three weeks during his term. Trump’s approach was codified in the December 2017 National Security Strategy, which labeled China a ‘revisionist power’ seeking to ‘displace the United States in the Indo-Pacific region… and reorder the region in its favor’. Openly acknowledging strategic competition with China, the Trump administration targeted Chinese technology companies, mused about restricting the numbers of Chinese students in American universities, and sought to decouple the two countries’ intertwined economies.

Tensions between Washington and Beijing rose dramatically through the Trump years. Multiple unsafe encounters occurred between the two nations’ forces, always instigated by Plan ships or PLA Air Force planes. Xi Jinping, who was chairman of the Central Military Commission in addition to being general secretary of the Chinese Communist party (CCP) and president, had told his military as far back as 2018 to ‘prepare for war’. His exhortations against American interference in China’s rightful sphere of interest increased over the succeeding years, leading to risky actions by Chinese sailors and pilots. While high-level bilateral diplomatic meetings continued to take place, they produced no solutions, and both sides recognized that such gatherings were increasingly for show.

Joseph Biden initially downplayed China’s threat during the early stages of his successful presidential campaign. But after coming to office in 2021, he promised to maintain US pressure on China. Beijing responded in the first days of the Biden administration by drawing explicit red lines over issues like Taiwan, Hong Kong and Xinjiang. This led to continued jockeying between Washington and Beijing during Biden’s single term, with the US president often taking a rhetorical hard line while looking to diminish tensions. Plans to reduce supply-chain reliance on China were only partly realized. Further limiting its ability to pressure Beijing, the US continued to fail to come up with a viable domestic 5G industry.

All this took its inevitable toll on the publics of both nations. In November 2022, the 20th National Party Congress of the Chinese Communist party extended Xi’s rule as paramount leader, which was widely expected, and inserted a policy plank seen as a preemptive declaration that China would seek hegemony over the South China Sea by 2049. Public opinion polls taken in 2024 showed that the percentage of respondents in China and the United States with a positive opinion of the other country had dropped to single digits, and that each considered the other its foremost potential adversary. In short, the political relationship between the United States and China had deteriorated to such a degree by 2025 that relations seemed nearly unsalvageable.

September 6-9, 2025: the gray rhino

The Littoral War of 2025 began with a series of accidental encounters in the skies and waters near Scarborough Shoal, close to the Philippines in the South China Sea. Beijing had effectively taken control of the shoal, long a point of contention between China and the Philippines, in 2012. After Philippine president Rodrigo Duterte, who had steadily moved Manila toward China during the late 2010s, was impeached and removed from office, the Philippines’s new president Leni Robredo moved to reassert Manila’s claim, in the early summer of 2025 sending coastal patrol boats into waters near the shoal. When People’s Armed Forces Maritime Militia (PAFMM) vessels pushed out the Filipino forces in early July, Manila appealed to Washington for assistance under its security treaty.

The new US president, Kamala Harris, had been dogged during the 2024 campaign by allegations that Chinese cyber operations had benefited her candidacy, and that, with little foreign policy experience, she was unprepared for dealing with China. She saw the Philippine request as a chance to prove her willingness to take a hard line against Beijing. In the summer of 2025, Harris increased US Air Force flights over the Scarborough Shoal, using air bases made available by Manila, and sent the aircraft carrier Gerald R. Ford, along with escort vessels, on a short transit. Both sides knew some type of armed encounter was increasingly possible, if not probable, yet both seemed to ignore the risk. This led pundits to call the events surrounding the clash a ‘gray rhino’ — everyone knows rhinos can be risky and unpredictable, and you ignore them at your peril. Unlike the complete surprise of a ‘black swan’ event, if you’re keeping your eyes open you should see a rhino coming. (Ironically, Xi Jinping himself had warned about the dangers of ‘gray rhinos’ back in 2018 and 2019.)

In response to the brief uptick in US Navy Fonops near other Chinese-claimed islands in the Spratly and Paracel chains, Beijing decided to fortify Scarborough Shoal by building airstrips and naval facilities as it had done in the Spratlys. As Scarborough lies only 140 miles from Manila, China’s announcement set off alarm bells in the Philippines. At this point, on Saturday, September 6, US Indo-Pacific Command, acting directly under orders from US secretary of defense Michèle Flournoy, dispatched USS Curtis Wilbur, a guided missile destroyer, and USS Charleston, an Independence-class littoral combat ship, to the waters off Scarborough, and ordered the aircraft carrier John C. Stennis to head from its home port in Bremerton, Washington, to Pearl Harbor. Another guided-missile destroyer, the USS Stethem, and a mine countermeasures ship were ordered to transit the Taiwan Strait.

The next day, Beijing announced an air-defense identification zone over the entire South China Sea, and demanded that all non-Chinese aircraft should submit their flight plans to Chinese military authorities before attempting to proceed.

On Monday September 8, at approximately 18:30 local time, a US Navy EP-3 surveillance flight out of Japan over the Spratlys was intercepted by a PLAAF J-20 taking off from Fiery Cross Reef in the same chain. After warning off the American plane, the J-20 attempted a barrel roll over it. The Chinese pilot sheared off most of the EP-3’s tail and left rear stabilizer; his plane lost a wing and went into an unrecoverable spin into the sea. The EP-3 also could not recover and plunged into the sea, killing all 22 Americans aboard. Tragically, the EP-3 shouldn’t even have been in the air: the US Navy had intended to replace the fleet with unmanned surveillance drones as early as 2020, but the Biden administration’s post-COVID-19 defense cutbacks led to occasional use of a limited number of the aging manned aircraft.

Roughly 30 minutes later, before word of the EP-3’s downing reached US Indo-Pacific Command in Hawaii, let alone Washington or Beijing, the Bertholf, a US Coast Guard cutter, and the Motobu, a Japan Coast Guard patrol vessel, were returning from a joint training mission when they were approached 13 nautical miles northwest of Scarborough Shoal by an armed Chinese Coast Guard (CCG) cutter. After broadcasting warnings for the Bertholf and the Motobu to leave the area, the Chinese ship attempted to maneuver in front of the American ship in order to turn its bow. The CCG captain miscalculated and struck the Bertholf amidships, caving in the mess and one of its enlisted-crew compartments. The CCG ship immediately left the scene without rendering assistance. Six US sailors later were declared missing and presumed dead in the collision, and three Chinese CCG sailors were swept overboard and lost at sea.

The Curtis Wilbur was the closest US naval vessel to the downed EP-3, and it raced toward the crash location while the Charleston moved to assist the Bertholf. Night fell, and the darkness caused confusion for both sides’ rescue and patrol operations. Two Plan ships returned to the scene of the maritime collision to search for the lost Chinese seamen, coming in close quarters first with the Motobu, which was helping operations to stabilize the Bertholf, and later with the Charleston, which arrived several hours later. In the dark, American and Japanese ships struggled to disengage from the Chinese vessels, while continually warning the other side to stand down so rescue operations could continue.

After several close encounters, a Chinese destroyer, the Taiyuan, activated its fire-control radar and locked on the Motobu. The captain of the Motobu, knowing he could not survive a direct hit from the PLAN destroyer, radioed repeated demands that the radar be turned off. When no Chinese response was forthcoming, and with rescue operations ongoing, the Motobu’s commander fired one round from its deck gun across the Taiyuan’s bow. In response, a nearby Chinese frigate, thinking it was under attack, fired a torpedo in the direction of the Motobu. In the congested seas, however, the torpedo hit the Charleston as it transited between the Chinese and Japanese ships, ripping a hole below the waterline. Early on Tuesday September 9, the lightly-armored littoral combat ship, with a complement of 50 officers and seamen, foundered in just 25 minutes with an unknown loss of life.

September 9–11: the choice for war

When word of the aerial and maritime encounters began filtering through to USS Blue Ridge, the flagship of the Seventh Fleet, and to US Pacific Fleet headquarters in Hawaii, rescue operations were immediately ordered. Within 20 minutes, the Gerald R. Ford was ordered to steam to the location, provide rescue operations, and protect all US and allied shipping in the South China Sea.

Elsewhere that day, two US F-35s flying out of Japan encountered four Chinese J-20 fighters. A short aerial standoff turned into a lopsided dogfight in which all the Chinese planes were shot down at the cost of one US jet. In response, the PLA Chief of Staff recommended missile attacks on US airbases in Okinawa; this, however, was vetoed by Xi Jinping in his role as Chairman of the Central Military Commission (CMC). Many Chinese analysts now consider Xi’s decision not to attack Japan in the earliest stages of the conflict a strategic error that prevented complete Chinese victory.

After the dogfight, US Pacific Fleet headquarters in Hawaii ordered the Curtis Wilbur to defend the Bertholf and disable any Chinese ship that interfered with ongoing rescue and repair operations. The US Pacific Air Force was ordered to maintain steady air cover and intercept any Chinese fighter jets from entering a 20-mile radius around the accident site. At the same time, all mission-ready Seventh Fleet combat forces were ordered to steam at full speed from Yokosuka, Japan for the Spratlys. To intimidate the Chinese, B-52s based in Guam commenced regular overflights of Chinese bases in the Spratlys. President Harris also approved deployment of the aircraft carrier John C. Stennis and three more destroyers from Hawaii to the South China Sea, along with three nuclear attack submarines (SSNs).

The American response was intended to sanitize the immediate area of the clash, but not to widen the theater of operations or prevent Chinese ships and planes from transiting the South China Sea, except for the area in which the Americans were concentrating on rescue operations. This ‘minimum deterrence’ approach made political sense, but it ultimately created opportunities for Beijing to take military advantage of American hesitancy. An urgent phone call between Presidents Harris and Xi on the evening of September 10 did little to stabilize the situation.

That night Beijing time, Chinese state media spread a doctored video of the ramming of the Bertholf that made it look like the Americans were to blame for the accident. Chinese internet censors allowed the clip to become a viral sensation. Almost immediately, stage-managed crowds thronged the gates of the American and Japanese embassies, demanding compensation from Washington and Tokyo. Xi took to the airwaves to chastise the Americans, but he also tried to rise above the fray by announcing that China would not further deepen the crisis. This tactic backfired.

Crowds began moving toward Tiananmen Square, demanding that China push America out of Asia. The Chinese internet lit up with criticism that questioned Xi’s mental state. Chinese overseas students and provocateurs under guidance from the CCP’s United Front Work Department propaganda unit began coordinated protests in Sydney, Seoul, London, Paris, Toronto and Vancouver, while small groups of Chinese students at US universities, including Harvard, Columbia, UC Berkeley and UCLA, staged demonstrations that garnered widespread media coverage. The demonstrations threatened to split the Democratic party, with activists supporting the Chinese students, and Congresswomen Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Ilhan Omar and Rashida Tlaib demanding a withdrawal of US forces from the region. On September 11, after emergency meetings of the Chinese Communist party’s Standing Committee and the Central Military Commission (CMC), Xi reversed his previously cautious course. He ordered the Plan to block all US ships from coming into China’s ‘historic waters’ of the South China Sea, and to either escort out or capture any US vessels remaining there. He also imposed a no-fly zone over the Spratlys and Paracels. Moreover, he promised to target any Japanese naval ships that accompanied US vessels into the South China Sea. However, Xi continued to reject suggestions that American airbases in Japan or Japan’s own airbases be targeted immediately with ballistic missiles, a decision that caused deep resentment within the PLA.

September 12-15: the Taiwan Strait is lost

First blood in the expanded theater of operations was drawn by the Chinese on September 12. USS Stethem and USS Patriot, previously ordered to transit the Taiwan Strait, were caught in a swarm of Chinese fishing craft, missile patrol boats and Chinese Coast Guard ships that had crossed the median line at a point about halfway through the strait. Slowed to a crawl by the swarm of small craft and alarmed by their threatening tactics, the Stethem felt forced to fire warning shots. This resulted in a missile swarm fired from the small Plan patrol craft, which apparently had orders to attack the US ships if they gave any justification. Both US ships sustained casualties and serious damage, but returned fire, disabling one of the CCG ships and driving off the others.

The Stethem and the Patriot eventually broke free of the swarm and limped to Kaohsiung, Taiwan. This allowed Beijing to claim on September 13 that Taiwan was now a belligerent and to announce that the Taiwan Strait was closed. China sent a blockading force to Kaohsiung, stopping just outside Taiwan’s 12-mile territorial limit; positioned two more destroyers for anti-air missions over the Taiwan Strait; and began multiple combat aerial patrols around the island.

The next three days slowed to a dead calm in the region as the various task forces and ships of both sides neared each other. Neither Harris nor Xi was willing to declare war on the other country, with all the implications that held. Yet despite repeated phone calls between the leaders, neither agreed to pull back forces. Instead, Harris approved the dispatch to Japan of 10 more destroyers and two cruisers from San Diego, though their transit would take at least two weeks. Another two squadrons of F-22s were ordered to Kadena AFB in Okinawa, and two B-2 bombers from Whiteman AFB in Missouri made a transoceanic flyby over the Senkakus. But when Harris asked for permission to base the F-22s at Clark Air Base in the Philippines, widespread anti-US protests broke out, including massive demonstrations that besieged the base. These were organized and directed by Chinese intelligence agents, but they served to paralyze Philippine politics, especially once former president Duterte emerged at the head of the protesters and demanded that Manila restore peaceful relations with Beijing.

On September 15, the Plan South Sea Fleet task force reached the Curtis Wilbur, still guarding the crippled Bertholf off the Spratlys. Entirely outgunned, the Curtis Wilbur’s commander chose to batten down the ship and refrain from further hostilities, hoping to ride out any Chinese attack until relief forces could arrive; the Chinese, who had orders only to isolate the two American ships, formed a barrier around the Curtis Wilbur. In the skies, US tankers were withdrawn from their refueling stations, as US Pacific Air Forces feared losing their limited number to PLA fighters. With the Philippine president refusing permission for further US air operations from Clark, US fighter support over the South China Sea was effectively suspended.

September 16: the Battle of Bashi Channel

The next day, September 16, the Chinese aircraft carrier Liaoning, which was approximately 175 nautical miles northwest of Luzon in the Philippines, launched jets to try to intimidate the Gerald R. Ford, southeast of Okinawa.

The Chinese planes were decisively defeated by the Gerald R. Ford’s F-35s along with F-22s launched from Okinawa. This effectively prevented the Liaoning and its flotilla from moving forward. At the same time, the US escort ships also halted just within visual range of China’s East Sea Fleet vessels on the horizon. The clashes now threatened to involve land-based forces. This would have escalated the war to a higher, possibly uncontrollable, level. The US Pacific Fleet had anticipated the employment of land-launched DF-21D anti-ship ballistic missiles against the Gerald R. Ford, and indeed two were launched from Chinese territory approximately four hours after the aerial engagement, but they missed their target. Some in Washington chose to believe the failed missile attack was purposeful, with Beijing trying to send a message that it would knock out the Gerald R. Ford were it to continue into the South China Sea. Within three hours of the attempted DF-21 strike, orders went from Washington to the Gerald R. Ford: the US carrier was to hold position east of the Bashi Channel. A hundred miles north of Luzon and 120 miles south of Taiwan, the channel essentially forms the border between the Philippine and South China Seas.

The strategic implications of sending US aircraft carriers into Beijing’s ‘kill zone’ of land-based ballistic missiles, missile boats and submarines were becoming clear. In Washington, the planners were in a quandary. The Gerald R. Ford remained within missile range, but officials were loath to pull the carrier farther back for fear of being seen as abandoning the conflict. Nor did they want to risk an escalation of hostilities by targeting Chinese assets not directly involved in the skirmishing. Again, it appeared that the Chinese had checked the Americans, though without knocking them off the board.

When word reached Taiwan that the Gerald R. Ford had halted, the island’s president, from the mainland-leaning Kuomintang (KMT) party, announced on September 17 that Taiwan was henceforth neutral in the conflict, and would accept Chinese naval patrols of its sea-lanes, and overflight.

September 17: the Chinese use electronic warfare

After one day on station, on September 17 the American ships, except for the Gerald R. Ford, continued toward the Spratlys. The PLA Strategic Support Force then began wide-scale electronic warfare measures and cyberattacks on US systems, after hesitant moves to interrupt US systems in the first week of the conflict. It succeeded in repeatedly interrupting GPS and shutting down various US computer and communications systems, including intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) feeds, through malware. US electronic-warfare aircraft launched from the Gerald R. Ford and Japan also found their systems jammed, leaving US commanders reliant on incomplete information from satellites and submarines. This significantly slowed the progress of the US flotilla toward the Spratlys and was only partially countered by dozens of line-of-sight communications transmitters tethered to medium-altitude balloons, launched from US Navy ships scattered throughout the theater of operations. With the advent of electronic warfare, US policymakers began to fear that a future wave of cyberattacks would widen the field of conflict to civilian systems, forcing a major US response. For the time being, however, the Chinese hesitated to escalate the crisis horizontally by targeting noncombatants, focusing instead on crippling US operations in the theater of combat.

September 22: the Battle of the Senkakus

The Japanese now played an unexpected role. In the early hours of Monday September 22, the Soryu diesel-electric attack submarine lurking southwest of the Senkakus intercepted the Chinese aircraft carrier Liaoning and hit her with two torpedoes. The Liaoning was halted and began to list, at which point the sub surfaced and launched six Harpoon missiles. Four of them found their target, leaving the Liaoning out of commission and severely listing to port. Four Chinese attack submarines that had been in Taiwanese waters then hunted down the Soryu, sinking her with all 65 hands on board.

When intelligence of the disabling of the Liaoning reached East Sea Fleet headquarters at Ningbo on the Chinese mainland, it was assumed that the Liaoning had been hit by an American submarine. In response, orders went out to retaliate by targeting the Gerald R. Ford, which had turned north from the Bashi Channel after receiving word of the battle off the Senkakus. As they had on September 16, the Chinese launched DF21D anti-ship ballistic missiles. This time, however, two missiles found their target after ineffective countermeasures. The Gerald R. Ford sustained catastrophic damage and severe loss of life, and the ship foundered at nightfall. Japanese and American ships sent out from Okinawa reached the scene late on September 23 and commenced rescue operations. The second American aircraft carrier, USS John C. Stennis, hove into view the following day.

September 23-30: the choice for peace

The successful attacks on both Chinese and American aircraft carriers were the turning point of the Littoral War. Senior policymakers in both countries realized they were now at the precipice of a full-out conflict in which land-based targets and civilian populations would be targeted. Standard operating procedures at US Strategic Command, which controlled America’s nuclear arsenal, had moved readiness on September 10 from peacetime Defense Condition (Defcon) 5 to Defcon 4, and then on September 12 heightened it to Defcon 3, with enhanced readiness at underground missile silos and the ability to mobilize nuclear-armed bombers on ground alert. At the same time, the PLA Rocket Force had gone to high alert on September 11.

After the Battle of the Senkakus, the expansion of the war to land-based, populated targets would have been the next logical military step, but the US’s political and military leaders were loath to take it. More worrisome for operations planners in both countries was the likelihood that the Americans would begin targeting mobile DF-21D and DF-26 launchers on China’s mainland to prevent the PLA from using more anti-ship ballistic missiles. Such attacks would force the Chinese to begin attacking ground targets in response, possibly on Guam and even Hawaii, as well as US air and naval bases in Japan.

Perhaps unexpectedly, the first steps toward a cessation of hostilities were proposed by the Chinese. The Plan’s attack on the Gerald R. Ford, an erroneous retaliation for the Liaoning disabling, caused a rift in the Chinese leadership. Xi Jinping upbraided the East Sea Fleet leadership for not confirming that the Americans were behind the attack, a point also made by President Harris in a nationally televised address on September 23. Xi also concluded that an attack on another US carrier, the John C. Stennis, would likely lead the Americans to begin large-scale operations against Chinese land-based missile targets, docks, shipyards and air bases. With more US ships reaching the theater of battle, it would be harder to control the conflict.

Beijing could wind up losing the gains it had made: eliminating the American presence in the South China Sea and taking control of the Taiwan Strait with a neutralized Taiwan. Xi therefore contacted Harris on the morning of September 23 and proposed an immediate cease-fire, to be followed by negotiations between military commanders for a permanent halt to combat operations.

President Harris faced a different set of constraints than Xi. With one aircraft carrier gone, the US Navy had only two fully operational carriers left from the total force of nine. It would take weeks to bring two more carriers up to combat readiness, and months to get another two ready for deployment. The US Navy had also deployed the majority of its combat-ready destroyers and submarines, and further losses from missile attacks would begin to seriously degrade the US capability to wage surface war. The US Air Force had outclassed its Chinese opponents, but its number of mission-ready airplanes was declining, as well as its stores of air-to-air missiles. Surging both naval and air units to the region left little in reserve for a longer conflict.

At home, fear of an all-out war with China split public opinion, with a plurality supporting an end to US military operations in the region. Isolationists in both political parties waged an effective media campaign, questioning whether Harris had an actual strategy for the conflict and afterward. A grim balance had been achieved with the mirror attacks on the aircraft carriers. Harris responded positively to Xi’s proposal, contingent on the immediate release of all US military personnel held by the Chinese. Xi consented, promising that they would be transferred to the Philippines by Chinese ships, beginning on September 25. The two agreed that all combat operations would cease at 11:00 Beijing time on September 24 and all forces would hold their positions.

Aftermath: a cold peace

Since neither side had taken any territory, Harris and Xi agreed to ratify the military status quo at the time of the ceasefire and avoid bringing in the diplomats. The commander of US Indo-Pacific Command met the chief of the Joint Staff Department of the PLA’s Central Military Commission in Singapore on September 26, and they reached an agreement on a permanent cease-fire on September 28.

Each side agreed to inform the other of naval and air activities taking place in the Yellow, East and South China Seas. The US would notify Beijing of any passage of US naval ships through the South China Sea, while China would undertake to ‘limit’ but not cease its naval activities in the East China Sea. Further, the US recognized Chinese control over the Spratly and Paracel island chains and acknowledged China’s ‘historic interests’ in the South China Sea. For its part, the PRC promised never to invade or attack Japan, provided Japan refrained from interfering with peaceful Chinese military activities in the East China Sea. (A secret codicil, revealed five years later, contained an American promise to end all military and intelligence aid to Taiwan, effectively killing off the 1979 Taiwan Relations Act.)

After the agreement was made public, President Harris announced a withdrawal of US naval, ground and air forces from Japan to Guam and Hawaii; the US would leave a token force of one F-16 squadron and two guided-missile destroyers in Japan but withdraw completely from Okinawa. The US-Japan alliance would instead be maintained by enhanced military aid to Japan and full intelligence sharing along the lines of the ‘Five Eyes’ arrangement. In the interests of maintaining peace on the Korean Peninsula, the US Army would reduce its forces in South Korea from 28,000 to 7,000 soldiers, 3,500 of them in combat units, with all of them to be located in Busan, on the southern tip of the country. Seeking to reassure America’s allies, Harris reiterated that America’s extended deterrence commitments, the ‘nuclear umbrella’, would remain in force. Harris’s policy shifts caused an uproar among mainstream foreign policy experts, but they were applauded on both the progressive left and isolationist right of the political spectrum.

Beijing concluded that its victory was a prelude to squeezing the reduced American-led alliance and steadily pressuring the nonaligned bloc. In public, Chinese officials repeatedly maintained that Beijing considered the diplomatic solution merely ‘temporary’, and that China would not rule out further action to follow up on its gains, but it failed to activate any plans to take advantage of its success. Beijing soon discovered that its new allies were resentful and unwilling partners, requiring the investment of Chinese political, economic, and military capital. This restricted Beijing’s freedom of action.

The United States limited its strategic goals to protecting Japan and ensuring that it could operate in part of East Asia’s marginal seas (the eastern portion of the East China Sea) as well as beyond the outer crescent of Japan. This allowed for the possibility of power projection into the inner seas and littorals in a future crisis, but turned the US largely into an ‘offshore balancer’, with its forces concentrated in Hawaii and on Guam. The US’s surviving alliances with Japan and Australia were inherently weaker than before the war.

With the US and China willing to limit future operations to preserve gains or prevent further losses, the political conditions were created for a geopolitical settlement that resulted in the emergence of three geopolitical blocs: one comprising the US and Japan, along with Australia; a second led by China, with its new satellites of Taiwan and the two Koreas; and a third, ‘nonaligned’ bloc containing most of the members of the Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN), as well as India and Russia. The Chinese and American blocs were mutually antagonistic, while the third, nonaligned one maneuvered for advantage between the other two.

A cold peace settled on East Asia. Intraregional trade was reduced, though not eliminated, while multilateral diplomatic initiatives and mechanisms such as those sponsored by ASEAN became arenas for rhetorical combat. A sharp drop in Sino-US trade rocked both countries, with the United States entering a recession that lasted three years, while reports of widespread demonstrations in China hinted at pervasive domestic unrest. Trade slowly stabilized between the two, but some of the nonaligned countries — particularly India, Vietnam and Malaysia — retooled their economies to supplant China in the global supply chain, leading to a boost in their exports to America and Europe.

The Chinese and American blocs began a prolonged contest for influence in Asia. Beijing continued its military buildup, though at a slower pace than during the century’s first two decades, due to its economic slowdown. American defense planners increased their reliance on unmanned systems, hypersonic weapons, underwater systems and cyberwar capabilities. Both sides increased their espionage activities and conducted regular cat-and-mouse games in the skies and on the waters of the region. As of this writing, the two antagonists have so far avoided outright conflict. This may be as much through luck as from a shared wariness of stumbling once again into armed conflict.

Michael R. Auslin is the Payson J. Treat Distinguished Research Fellow in Contemporary Asia at Stanford’s Hoover Institution. This essay is adapted from his book Asia’s New Geopolitics: Essays on Reshaping the Indo-Pacific (Hoover, 2020). This article was originally published in The Spectator’s March 2021 edition.