What on earth is Donald Trump thinking? That’s what many realists and restrainers inside and out of Washington are asking themselves after news broke late last night that Marco Rubio, the senior senator from Florida, is set to be tapped as secretary of state in the next administration.

The reactions haven’t been uniformly bad, mind you. Other candidates rumored to be under consideration, such as Vivek Ramaswamy, caused many in the US foreign policy elite to wretch in fear. Others, like former national security advisor Robert O’Brien and Senator Bill Hagerty, who served as US ambassador to Japan during Trump’s first term, would have been predictable choices with whom most could live.

Rubio, however, is one of the most hawkish options Trump could have picked. Combined with the tapping of Mike Waltz as national security advisor and Elise Stefanik as US ambassador to the United Nations, the senior ranks of Trump’s foreign policy team thus far look mightily different from the loose “end wars, negotiate peace” framework the president referenced repeatedly on the campaign trail.

Much like what occurred during his first term, Trump is assembling a group of foreign policy advisors who are either lukewarm about Trump’s own vision for the world or fancy themselves significant authorities in their own right. During Trump 1.0, this produced a situation whereby Trump would say one thing — US forces will be withdrawn from Syria; America will reset its relationship with Russia; US alliances in Europe and Asia will be reexamined — and his senior advisors would work behind the scenes to stymie those initiatives. Look no further than US policy in Syria, when folks such as John Bolton, James Jeffrey and — yes — Brett McGurk, worked the machinery of government and convinced the president to disregard his instincts. Jeffrey even admitted, proudly, that he deliberately misled senior policymakers on how many American troops were actually in Syria.

Of course, nobody knows if Rubio would do something similar. Trump has yet to make an official announcement about Rubio’s supposed nomination for secretary of state yet, which suggests the infamously mercurial president is leaving his options open. And even if Rubio were formally nominated and confirmed — a certainty given the GOP majority in the Senate — there’s a decent chance Trump would tire of his one-time political opponent (Rubio ran against Trump for the GOP presidential nomination in 2016). This is the same guy who had four national security advisors and three defense secretaries in four years, after all.

With those caveats in mind, Rubio’s reported selection is puzzling because the Florida senator’s foreign policy philosophy is almost the polar opposite of Trump’s own. Next to Tom Cotton and Lindsey Graham, Marco Rubio is one of the most hawkish lawmakers on Capitol Hill, a man with a hammer searching for nails. Trump talks about getting US troops out of the Middle East; Rubio talks about keeping them where they are lest the region implode into a thousand pieces. Trump at least flirts with negotiating a nuclear deal with Iran; Rubio views negotiations with Iran as a fool’s errand at best and weak-kneed irresolution that pave the way for a nuclear-armed Iranian hegemon at worst. His more than decade-long record as a US senator screams “George W. Bush,” not “Donald J. Trump.” One similarity between Bush and Rubio: they both thought the 2003 invasion of Iraq was a righteous mission that made the world a safer place.

Rubio, no doubt, has experience. He’s the senior Republican on the Senate Intelligence Committee and has served for years on the Foreign Relations Committee. To his credit, he takes those positions extremely seriously.

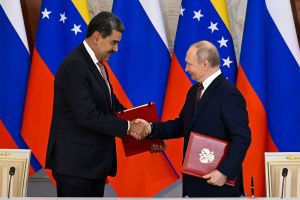

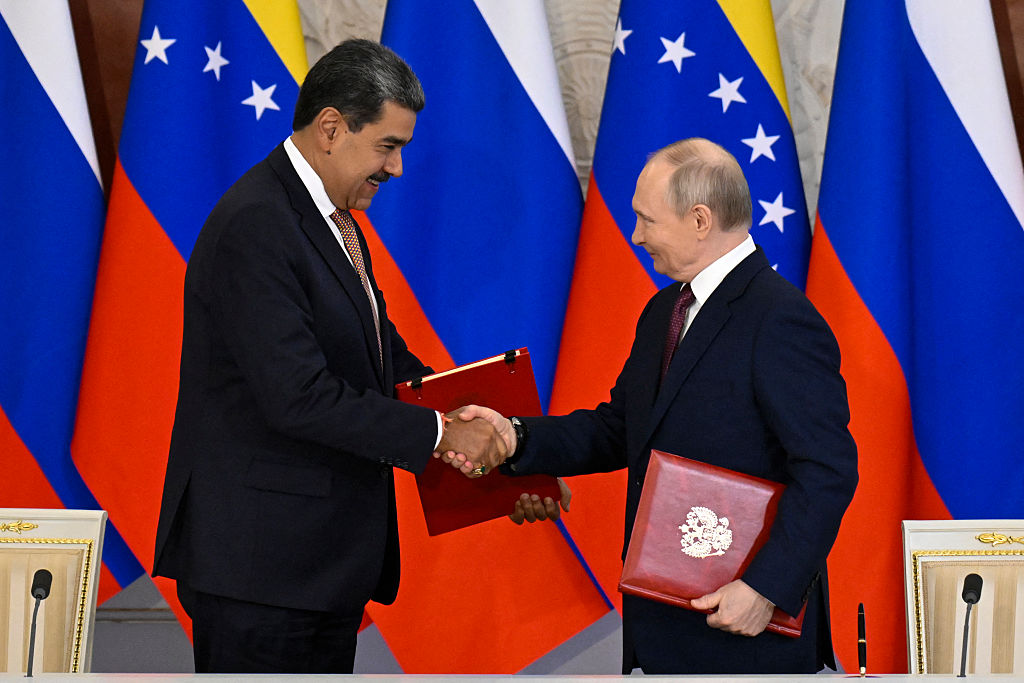

But experience and wisdom aren’t the same thing. If Trump wants good advice, it’s hard to see why he would go to Rubio for it. Along with other notables such ad Bolton and Elliot Abrams, Rubio was an intellectual brainchild behind the maximum pressure policy on Venezuela, which was supposed to squeeze Venezuela dictator Nicolás Maduro so tightly that the mustached former bus driver would have no choice but to essentially hand over the keys to the democratic opposition. It didn’t happen. Rubio was a key supporter in the Senate of another maximum pressure policy, this time on Iran, which produced nothing more than a higher risk of war in the Persian Gulf and an Iranian nuclear program that has expanded in both quantity and quality.

It should also be noted that Rubio undermined Trump during his first term. In 2019, after Trump opined about getting the US out of Syria and Afghanistan, Rubio went to the Senate floor and delivered a speech stressing why such withdrawals would be premature, embolden ISIS, kill America’s credibility and result in terrorists running rampant. He voted for a resolution that opposed such withdrawals from taking place. “Now people may say what’s wrong with this,” Rubio, talking about withdrawal, said at the time. “Get out of Syria, Iraq, Afghanistan, why are we fighting other people’s wars? We’re not. This is not other people’s wars. This is ours.” Does Trump really feel the same way?

Some will argue that Trump needs a cabinet that will challenge him on critical issues. This is a fair point; whether it was the Lyndon B. Johnson or George W. Bush administration, the United States doesn’t excel when a groupthink mentality takes ahold of the policy process.

But like all presidents, Trump also deserves advisors who will implement his policies when a decision is made. Will Marco Rubio do that? I’m open to being persuaded, but my skepticism runs deep.

Leave a Reply