Because teachers’ unions play such an important role in today’s Democratic Party, it is widely assumed that school choice — the policy of letting families use taxpayer dollars to educate their children as they wish — is a Republican or conservative program. And while it’s true that teachers’ unions will instantly turn on any Democrat who favors public funding of non-public schools, there is in fact a long history of prominent left-wing thinkers and activists supporting school choice.

As far back as 1956, British Labour Party leader Anthony Crosland wrote a controversial book called The Future of Socialism, in which he observed that the bureaucratic management of England’s newly expanded welfare programs was turning out to be almost as bad as having no programs at all. He argued that the most efficient and effective way to provide many social benefits, including education, was by distributing service-related vouchers, which recipients could spend in whichever way they saw fit. This was just one year after American economist Milton Friedman first outlined the concept of school choice in his essay on “The Role of Government in Education.”

And while is largely forgotten today, the person most responsible for establishing America’s first modern choice program was a black activist and community organizer in the Wisconsin legislature named Annette “Polly” Williams. Up through the late 1980s, the state’s conservative Republican governor, Tommy Thompson, had been trying to provide government subsidies for the children of poor Milwaukee families to attend private schools, but to no avail. It was Williams who finally organized the grassroots coalition of parents, civic leaders, and politicians from both parties which made the 1989 Milwaukee Parental Choice Program, still running today, possible.

Then, too, there is the case of former Harvard Law professor Elizabeth Warren who, prior to running for the US Senate from Massachusetts (where no Democrat can win the party’s nomination without pleasing the teachers’ unions), was one of America’s most thoughtful and outspoken school choice advocates. Warren’s research on bankruptcy had led her to see that the major cause of middle-class families becoming insolvent was not too many trips to the mall or some other profligacy but failing to keep up with mortgage payments on expensive homes in the relatively few towns with desirable public schools. “What’s happening,” she realized, “is that young parents buy houses with just three thoughts in mind: schools, schools and schools.” The problem is that “in inflation-adjusted dollars, they’re paying… 70 percent more than their parents paid for a house…”

The solution, as Warren explained to the Massachusetts policy quarterly CommonWealth in fall of 2003, is simple: “Decouple school assignment and ZIP code… then the economic pressure on families would be released almost immediately.” In other words, if parents were subsidized to educate their kids however and wherever they wish, they would no longer need to buy high-priced homes beyond their means.

Among the many other American liberals who have advocated for school choice over the years are Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s chief strategist Wyatt Tee Walker, former Harvard Graduate School of Education dean Ted Sizer and Senate icon Daniel Patrick Moynihan. And outside the US, in socially progressive countries like Australia, Denmark, the Netherlands and Sweden, school choice has been both legal and popular for decades.

That there has always been a left-wing sympathy for school choice should come as no surprise, given its potential to provide poor and minority children with a far better education than the one they can get at most urban public schools. Indeed, once the right began to promote choice as a civil rights issue — and not just way to give parents more of a say in the schooling of their children — it was evitable that at least some Democrat state legislators would go along, even at the cost of angering their party’s biggest financial backer, the teachers’ unions.

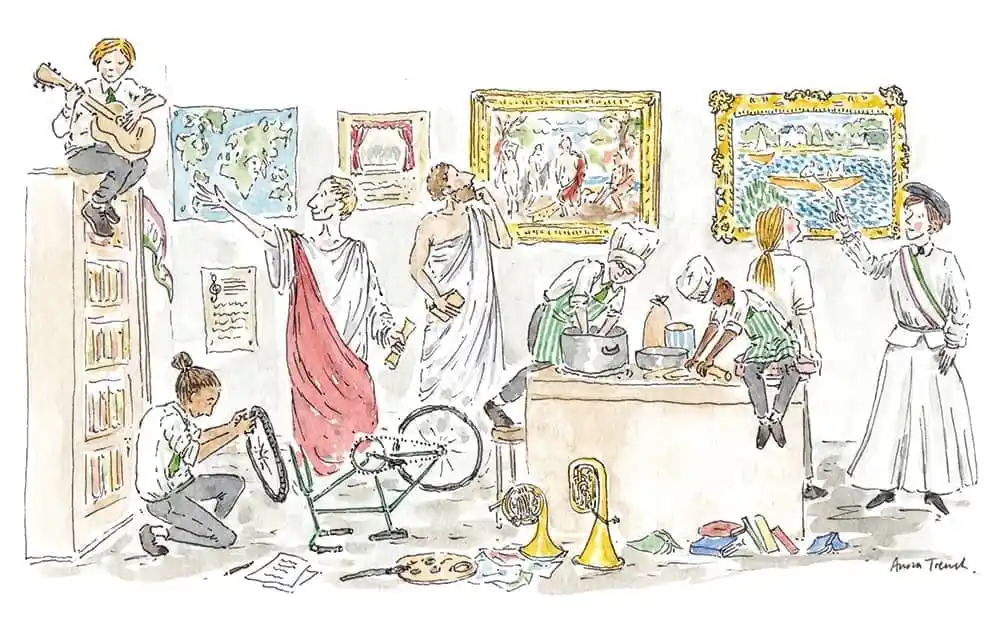

But as recent events are beginning to make clear, school choice also satisfies another of the left’s longstanding goals: the dismantling of large, one-size-fits-all educational bureaucracies in favor of an approach to children which recognizes their unique interests and abilities. Ever since the French philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778) first argued that education should be based on the natural development of the individual, many left-wing intellectuals have continued to emphasize the importance of freeing students from a single, narrow curriculum. One of the most famous of these, the Austrian theologian and social critic Ivan Illich, even titled his most influential book, Deschooling Society.

During Covid, many American parents were forced by school closures to educate their children in small neighborhood groups, often using the same online software which has long been available to homeschoolers. Some of these collaboratives rotated among the families’ homes, others met in churches, and still others in rented storefronts; but it was not long before the press began to refer to them, first as “learning pods,” and eventually “microschools.”

It was just assumed that these improvised learning venues would automatically disappear when local public schools finally reopened. But as the pandemic subsided, something completely unexpected happened — the number of US microschools kept expanding, many with the financial support of newly enacted school choice policies in Arizona, West Virginia, Florida, Ohio and other states.

Once more, as Foundation for Economic Freedom senior education fellow Kerry McDonald has reported, they increasingly diversified to meet the unique needs and interests of their students, with settings that ranged from a downtown Philadelphia investment firm to an Oregon nature preserve. Today, according to Don Soifer of the National Microschooling Center, there are more than 120,000 microschools across the country, educating more than 1.5 million students. And all providing the kind of student-centered education which, except for the contemporary technological enhancements, is not that much different from what Rousseau himself had in mind.

It is unfortunate for the left that the Democratic Party’s financial reliance on the teachers’ unions has obscured the extent to which school choice represents the realization of one of its own longstanding goals. Even sadder for the country that in a time of bitter political polarization, free market conservatives and social justice liberals are failing to build on common ground.

But if history tells us anything, it is that even a faction as powerful as the teacher unions cannot forever cloak a logical collaboration. For as another famous Frenchman, Victor Hugo, once observed, “There is nothing more powerful than an idea whose time has come.”

Leave a Reply