You get a look at your high-school daughter’s smartphone. You see a note there, a note to you and your family. It’s a suicide note.

What to do, that is, what after seeing the troubled girl through time on a psychiatric ward? You sue.

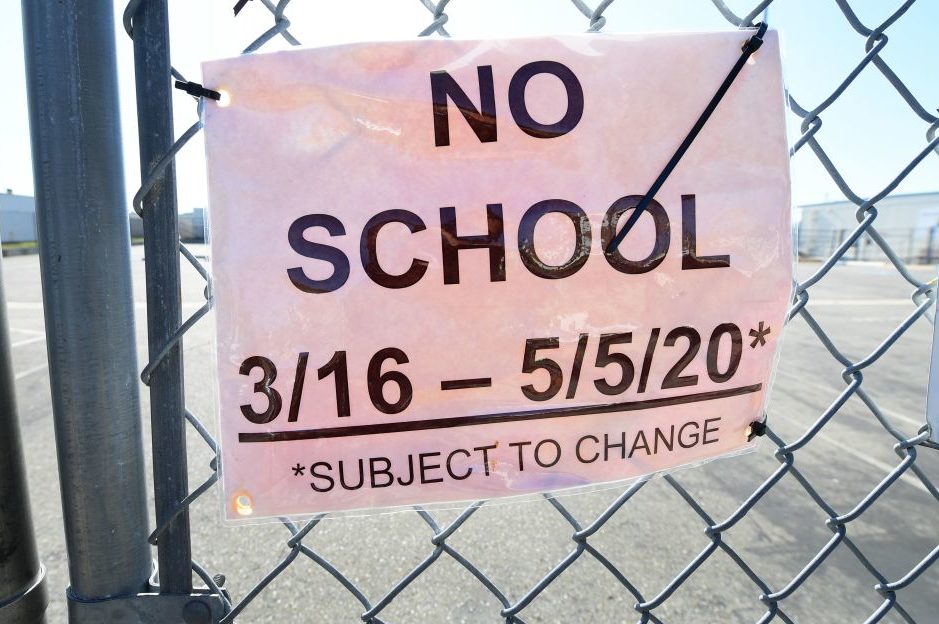

I refer to litigation brought by desperate parents in Los Angeles and San Diego counties in an effort to get their kids back into public schools. While looking into the effects of COVID lockdowns, I happened upon certain court documents. I have since been provided others by one of the plaintiffs’ law firms, Aannestad Andelin & Corn.

But let’s not consider these cases as literally what they are: legal prayers for relief in state courts, relief from persisting, on-and-off, lockdowns; relief from COVID hysteria. Rather let us, drawing from these papers, hold an imaginary trial.

We call our experts. Tracy Beth Hoeg, MD, PhD, an epidemiologist. She offers these estimates of relative risk: the prevalence of COVID disease in schools has been consistently lower than in their surrounding communities; fewer kids have died of COVID than die of the flu in a typical year. And the surveillance testing, Dr Hoeg, the spitting and nose-swabbing, could you give us your view? ‘Too problematic to justify the practice.’

Our next expert is Tim Kusserow, an education consultant with 25 years experience in elementary schools. What, Mr Kusserow, does going to school give kids? ‘Kindness, empathy, grit, resilience.’ And the book work? ‘I have never seen a child learn to read on a computer.’

We can bring on other experts: the social worker who will tell us teachers can see warning signals from kids in distress — but only if those kids are in school; the psychologist who will tell us which kids suffer most from missing school. Who else but poor kids?

But now let’s quickly move on to the testimony of parents, to their observations of their socially isolated kids. Apart from the girl who wrote the suicide note, we are told, there was another high-school girl, once thriving in the classroom and sports, who began to cry herself to sleep as the weeks out of any classroom turned to months. She slit her wrists. She survived. There was a high-school boy who tried to leap from a moving car. At the moment he was being driven to a therapy session that, it was thought, might bring him out of his new habit of staying alone in his bedroom. Another boy, this one a middle-schooler who had been struggling academically — he had some 1,100 unanswered emails from seven teachers — was transferred to a private school for classroom instruction. He brightened but then relapsed into his earlier blue funk. When he divulged thoughts of taking his own life, he was rushed to an ER. There he revealed his ‘detailed plan’ for suicide by electrocution.

Adolescents have their moods and complaints with or without school. We know that. But when we are told in this continuing testimony that a teenager previously ‘social’ and ‘a competitive athlete’ began to report ‘dark thoughts’, stopped eating, suffered panic attacks, wore a hoodie all day to cover her face and retreated from her family to curl up in a fetal position in bed, we might conclude her affliction had something to do with ‘distance learning’. Her therapist did.

How well did distance-learning work for an autistic child in kindergarten? An English-speaking kindergarten student in a Spanish-immersion class? Not well, their parents say, not well at all.

Even when a school reopened, kids wouldn’t necessarily find what they once knew. Next to testify is a parent telling of a third-grade son. After months without school, after telling his parents of suicidal thoughts, he moved on to his first day back in the classroom. Both parents work, they have two kids, and they couldn’t pick up the third-grader in the middle of the day when school let out. Thus the ‘Beyond the Bell’ program: kids waiting for their parents sat in tents — socially distanced within those tents, of course, of course, everything within the perfect order of state regulation. The boy came home ‘in full meltdown’. One of his parents: ‘My son said he felt like a prisoner sitting in a tent. My son begged me not to force him to go back to Beyond the Bell.’

Another parent simply rejected what a middle-school offered: ‘Zoom in a room.’ The kids with their masks and laptops and headphones were to listen to teachers who were somewhere else — who knew where? — doing what they could manage to teach remotely.

A summation for the jury: for more than a year now the young have borne the burden when their elders freaked out over COVID.

But against whom are the charges to be brought? Gov. Gavin Newsom? Sure. He has reigned capriciously by emergency order, meantime sending his own kids back to private school.

In the actual cases, outside our imagined courtroom, Newsom is in fact a defendant along with other state officials and five school districts. The litigation, in progress since February, has succeeded in relaxing state strictures on reopenings. How fast kids get back into the classroom now depends mostly on school boards and teachers unions.

But let’s stint on recrimination. Kids have been harmed across the country. Who among us might not be put in the dock? I know of public schools where teachers are finally back in classrooms because they have long wanted to be there — and still the kids don’t show up because their COVID-panicked parents won’t send them.

It’s all but too late now, too late for this school year. Yet with the contagion passing in this country, we might at least make a show of good sense over the next month: fling open school doors — everywhere and right now.