Recently, I ordered a pizza. Since the establishment was only a few blocks away, I decided to pick it up myself. Manning the cash register was a slouching paragon of the zoomer generation.

“Can I help you?” he asked in some patois that mixed English and bovine. I said hi and told him I was picking up a pizza. He tossed his bangs almost imperceptibly; a tsunami raced across the Pacific. Another employee then brought my pie, upon which my man seemed to slip into a persistent vegetative state, staring at some fixed point on the horizon while I swiped my credit card through the reader.

The check printed. On it was a line for a tip.

Before we go any further, I want to make clear that most service employees are nothing like my catatonic cashier. They work hard, often on holidays, often under grueling conditions, and deserve nothing but respect. But that doesn’t change the fact that, in that moment, I was not just asked for but pressured into furnishing a tip for someone who very well might have been a Disney animatronic.

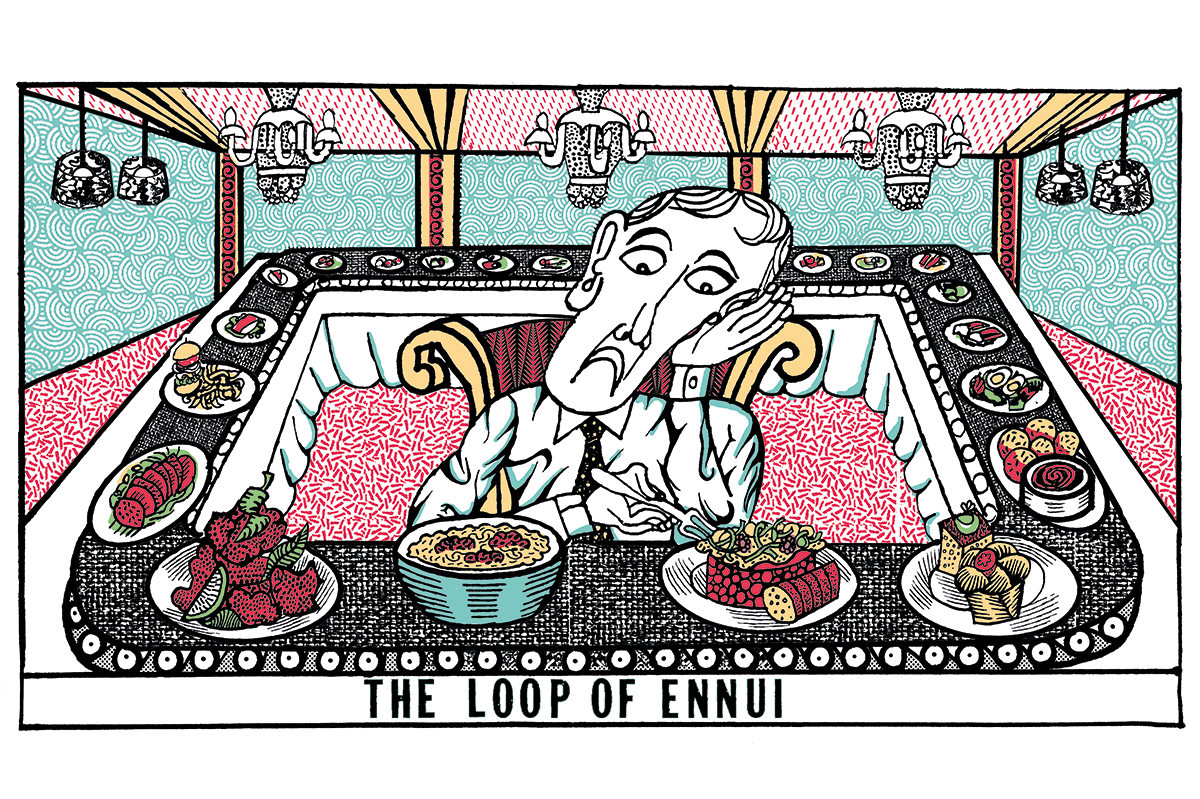

How did it come to this? Tipping is one of America’s greatest institutions, right up there with donut cheeseburgers and drive-thru Old Testament museums. Yet part of any tradition is grasping its context: where and when it applies. And in the case of tips, this has always meant some kind of exertion on the employee’s part: the waiter who hoofs across the restaurant to bring your food; the bartender who preps that Old Fashioned just right; the cabbie who leaves the bustling downtown to drive you fifty-five miles to the airport.

Admittedly this can lead to some gray areas. I once saw an older gentleman horribly offend a porter at a hotel because, after the porter had carried his suitcase up a single flight of stairs, he didn’t offer a tip. But then that’s just the point: tipping is supposed to be instinctive. It’s like pornography: you know it when you see it. And what everyone seemed to know, at least until a few minutes ago, was that standing behind a counter didn’t qualify you for tips.

Two culprits seem to be at work here. The first is credit cards, which insert the extra step of a signature between server and servee, allowing for a tip prompt on the check or machine. The second is the tablet-based payment system Square, which permits merchants to throw up a tip screen on any transaction. It even suggests tip amounts for you: 10 percent… 20 percent… 25 percent? A proper tip for even the best service used to be 15 percent. It isn’t just that tipping is expanding; it’s that the amount we’re expected to tip is being inflated by electronic suggestion.

All of this runs on the currency of our age: guilt. Of course, you don’t have to leave a tip, but then your cashier is probably making less than you, isn’t she? And surely you can afford just a little extra… right? There’s even a term for this nagging little angel on your shoulder: guilt tipping. It works by preying on that gray area, making you wonder whether it’s been expanded to all service employees, whether the guy manning the hammer game at the carnival is the next enraged hotel porter. It’s a subtle form of class anxiety but a very effective one.

The problem is that if everything merits a tip, then nothing merits a tip. This is the direction we’re heading in, starting with Washington, DC, which recently approved a measure that will phase out its tipping wage. Under current law, establishments such as restaurants can pay their servers at a rate of $5.35 an hour rather than the full minimum wage of $16.10 an hour. Systems like this are common across the country, given that the difference can be more than made up in tips. The new statute lumps everyone under the higher amount. And if a waiter is making that kind of money, why should he be tipped? Not everyone will overcome their guilt, but some will — and eventually that could congeal into custom.

It should say something that restaurant staffs widely opposed this measure — and those who like to eat out should too. Any American who’s ever been to Europe and bristled at the coldness and inefficiency of the service understands that our arrangement works best. “It really is glorious, your service culture,” writes the French-born author Pascal-Emmanuel Gobry. In Paris, Gobry says, “waiters are almost universally dour, unkind, frequently forget or mess up your orders, and generally scowly.” The reason? “In France, tipping is basically illegal. The waiter doesn’t have any reason to be nice.”

Whereas here in America, if anything waiters can be too nice. We’ve all had the experience of sitting down in a restaurant, taking a single sip of water, only for the maître d’ to come launching across the floor as though out of a cannon with pitcher in hand. Yet better this than rude indifference, right? The logic of American tipping is cold but true: people need a little extra motivation to put on a smile. If we universalize and thus devalue tipping, or do the same for wages, it won’t be that our service is universally polite. It will be that everyone turns into my rigor-mortis pizza gargoyle.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s February 2023 World edition.