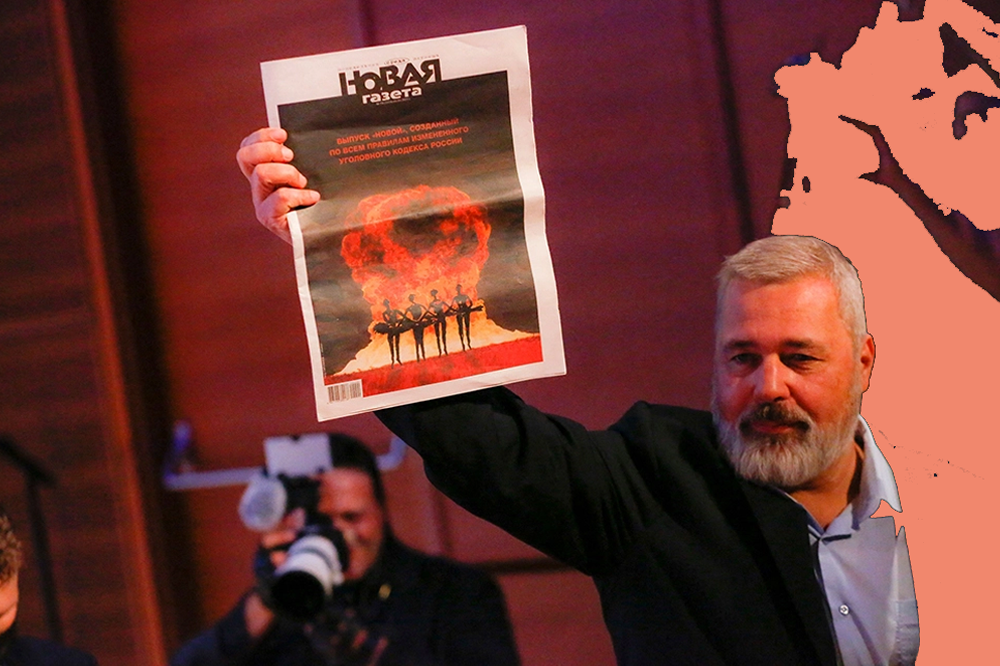

Before Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, there was a narrow but clearly defined space for Russia’s opposition media. The fearlessly anti-Kremlin Novaya Gazeta — whose editor-in-chief Dmitry Muratov was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize last year — was not only tolerated but funded by a regime-friendly oligarch at the behest of the deputy head of Putin’s presidential administration Sergei Kiriyenko. Radio station Ekho Moskvy was owned by Gazprom media but regularly aired scathing criticisms of the regime. And the independent Dozhd TV (“TV Rain,” motto: The Optimistic Channel) continued to broadcast online from increasingly cramped Moscow offices as advertisers and landlords were pressured to pull their support. Even as the Kremlin’s lavishly funded and ubiquitous propaganda machine filled the airwaves and internet with nationalistic, anti-western vitriol, Russians interested in alternative viewpoints could still freely access independent reporting from opposition journalists in Moscow.

After the invasion, however, that space snapped shut. A law was passed in the Duma punishing the speaking of “fake news” — defined as anything not confirmed in defense ministry statements — with up to fifteen years in prison, instantly criminalizing every opposition journalist in Russia. Novaya Gazeta and Ekho Moskvy were shut down and their staff, along with those of Dozhd and the English-language Moscow Times, fled.

Some Russian journalists ended up in Tel Aviv, others in Tbilisi, Georgia and Yerevan, Armenia. The Latvian capital of Riga became the obvious choice for Dozhd TV in exile as well as the newly founded Novaya Gazeta Europe. One reason was that Meduza, another independent media resource set up by former journalists from the lenta.ru news wire and funded by the exiled anti-Putin oligarch Mikhail Khodorkovsky, was already based there (its motto: “Make the Kremlin sad”). Another was that a third of the population of Riga are ethnic Russians. The anti-Putin exiles believed they and their independent journalism would be welcome.

They were wrong. This month Latvia’s media regulator, the National Electronic Mass Media Council, canceled Dozhd TV’s broadcasting license citing “threats to national security and public order” and fined them €10,000. Dozhd’s crime? In a report on Putin’s latest mobilization drive, the news anchor Alexey Korostelev asked viewers to provide information about terrible conditions facing called-up Russians and said: “We hope we can help many service members, for example, with equipment and basic amenities at the front.” Dozhd also showed a map of Russia that included the annexed Crimean peninsula. The reaction from the Latvian authorities and from Ukrainian netizens was extreme and immediate. The Latvian minister of defense Artis Pabriks called on the channel to “return to Russia,” while the country’s state security service also urged authorities to bar Korostelev from entering the country, and warned editor-in-chief Tikhon Dzyadko of potential “criminal liability.”

Dozhd apologized and immediately fired Korostelev for “misspeaking.” But its license was yanked anyway, to the delight of the Kremlin. “It seems to some people that other places are better than home, that other places have freedom, and there’s no freedom at home,” crowed Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov. “This example demonstrates the fallacy of such illusions.” The popular TV host Olga Skabeeva chimed in that the Dozhd ban proved that “the so-called freedom of speech in Europe is a lie.”

In truth, the staff of Dozhd — and indeed of Meduza, or Novaya Gazeta — are passionately anti-Putin. “I have responsibility as a Russian citizen for this war, as a journalist too, and I must do what I can to bring this idea home to a Russian society that is living in a bubble of propaganda,” says Mikhail Fishman, the anchor of one of Dozhd’s most popular news programs. “It is my duty to bring the truth about this war to the Russian public. If ten or twenty Russians see my reports and as a result tear up their call-up papers, then we will have done some good.”

So why the torrent of hatred? An anonymous graffiti artist summed it up when he (or she) scrawled “No Russians Welcome Here, Good or Bad” on a wall in Tbilisi, expressing a resentment widely felt in many of Russia’s neighboring countries against anti-Putin Russians who have chosen to flee rather than fight the Putin regime at home. In September, Poland, Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania banned all Russians from visiting for anything other than business or family visas. Even before the ban, Latvian authorities refused to issue more than thirteen work visas for Dozhd’s 100-strong editorial staff and immigration and tax officials visited the offices with “more inspections than we ever experienced in Moscow,” says a former senior Dozhd executive.

Many European politicians — including former Swedish foreign minister Carl Bildt — have condemned Latvia’s move as playing into the Kremlin’s hands. Mikhail Zygar, a political writer and former editor-in-chief of Dozhd, strongly suspects “the involvement of the Kremlin” in the takedown of Dozhd, in which passionate anti-Putin netizens played the part of useful dupes. Whether at the Kremlin’s behest or not, someone took considerable pains to search out old clips of Dozhd anchors appearing to express support for the annexation of Crimea and publishing them without context, when in fact they had been speaking ironically.

One function of Russia’s exiled media is to act as “a focal point and uniting factor for [Russian] emigrés who have no leadership, no institutions and nothing to unite behind,” says Zygar. But a much more vital function is to reach an audience inside their homeland and persuade them of a different narrative to the Kremlin’s. Hence Dozhd’s controversial references to the Russian military as “our army” and indignation at the terrible treatment of called-up soldiers — a key concern of many of Dozhd’s estimated 3.5 million YouTube channel subscribers inside Russia, who account for at least half their audience.

Exile publications have long played a key role in creating change inside Russia itself, from Iskra, Lenin’s early Socialist newspaper printed in Leipzig, Geneva and Clerkenwell, London, to the “tamizdat” emigré publications smuggled into Russia in the Soviet period. During the Cold War, the US’s Voice of America and Radio Liberty and the BBC’s Russian Service also received lavish funding for their key role in getting non-official news into Russia. But those were western voices. Dozhd, Meduza and Novaya Gazeta are recognizably made by Russians, for Russians. And that, to some, is their original and unforgivable sin.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.