This article is in

The Spectator’s inaugural US edition. Subscribe here to get yours.

As Donald Trump strides toward his fourth year in the White House, his enemies have yet to answer the most basic questions of 2016. Why is Trump president? Why not a nice Republican like Mitt Romney or Jeb Bush?

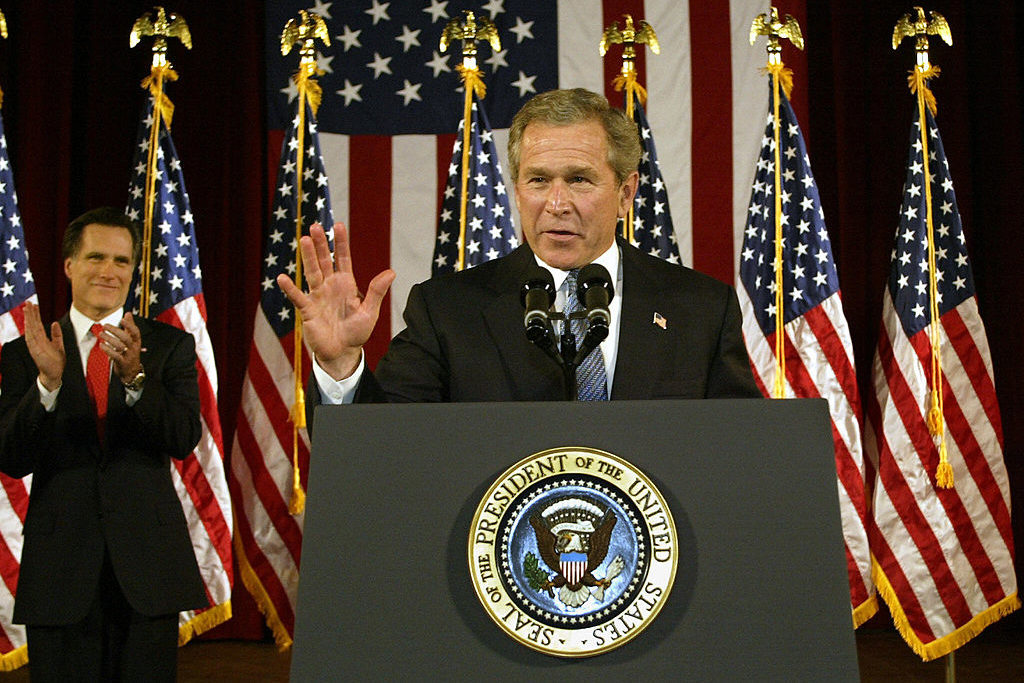

Two maps tell the tale. The first is the obvious one, the map of states whose electoral votes Trump won, a map that includes states like Pennsylvania and Wisconsin that no other Republican presidential aspirant had won since the 1980s. But the second map is even more important — it shows not why Trump won but why the Republican party was doomed to lose without Trump and Trumpism. It’s the map of George W. Bush’s re-election victory in 2004, the narrowest re-election, in terms of presidential votes, in recent US history. Bush prevailed by just 16 electoral votes, which meant that had either Florida or Ohio gone to John Kerry, the Democrats would have won. And Bush won Virginia, a state with 13 electoral votes that has since moved firmly into the ‘blue’ column.

Just do the math: a 16-vote margin minus 13 votes leaves the Bush victory map a single state away from defeat, and that state need not be a big one. New Mexico, Nevada or Iowa suffices. Colorado, Florida or Ohio would be more than enough. The ideological implications are as significant as the electoral ones. George W. Bush ran as a full-spectrum conservative, as conventionally defined. Bush cut taxes and promoted economic growth and an ‘opportunity society’. He was a social conservative opposed to abortion and same-sex marriage; religious right leaders endorsed him and his campaign considered ‘values voters’ the key to his re-election. And Bush was a war president, at a time when the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan were still popular. In 2004, he was everything the Heritage Foundation or National Review could have asked for, and he enjoyed the advantages of incumbency. He still won only narrowly, with a map that would hardly win at all for any future paladin of conservative orthodoxy.

Pennsylvania, Michigan and Wisconsin didn’t go for what Bush was selling. Those states did go for Trump, however, a Republican who bucked conservative orthodoxy on trade, foreign policy, immigration and — as is easily forgotten — a whole host of other issues, including at times gay rights, abortion and gun control.

The 2004 map didn’t leave old-fashioned conservative Republicans anywhere left to go. Maybe a future Bush Republican could have won New Hampshire, but that still leaves a very shaky path to the presidency. Returning Virginia to the red column might not be out of the question but it is highly unlikely: the state went to Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton in the last three presidential elections, both its US Senate seats have been held by Democrats since 2006, and four of its last five governors have been Democrats.

This is a result not just of demographic change resulting from an influx of immigrants but also the growth of a highly educated and — crucially — government-connected workforce, either employed directly by the federal government or based in northern Virginia to take advantage of the proximity to ‘the Swamp’. The best cause for hope Republicans can find in Virginia, based on how close GOP nominee Ed Gillespie came to defeating Democrat Sen. Mark Warner in 2014, is in fact cause for despair: 2014 was an optimal midterm year for Republicans, yet they still fell short. A presidential year is never less competitive.

Republicans already knew 20 years ago that they had an ideological problem. But even then they couldn’t figure it out: at the presidential level — and also the level of the conservative intelligentsia — the response to the populist challenges of Ross Perot and Pat Buchanan in the 1990s was to run away from populism and embrace what George W. Bush in 2000 called ‘compassionate conservatism’. That formula produced the 2000 map, which saw Bush prevail only with a favorable ruling from the Supreme Court. Bush redoubled his efforts to win religious voters in 2004, but more often the Republican establishment and conservative elite have responded to failure by moving even further away from right-wing populism. The ‘autopsy’ that followed the GOP’s drubbing in 2012 is a case in point: it prescribed that Republicans should talk and act more like Democrats on issues like immigration.

Yet the truth is that the country’s demographic and cultural shifts have destroyed not right-wing populism but orthodox conservatism and Bush-style Republican politics. There is no market on the right or the identity-politics left for what anti-populist Republicans are advertising. The center ground that the Republican establishment of 15 years ago was built upon has disappeared, in large part because of the establishment’s own policies. The Rust Belt wasn’t going to vote Republican to get another war in the Middle East, but it might vote Republican if it meant keeping more jobs in the United States — and it did vote for Trump in that hope, among other reasons.

The Republican party will not return to normal after Trump because the norms of 2004 are long gone, along with the map that just barely made the last Republican president’s re-election possible. Which is not to say that Trump’s new ideological formula for the party will work as well in 2020 as it did in 2016. But whatever happens next year, the GOP will have to decide on a new course very different from that of 2004, 2008 and 2012.

The Republican party ceased to be a party of landslide, all-American victory after Reagan left office (he was still around, after all, when George H. W. Bush won in 1988), and the post-Reagan party had its high-water mark in 2004 — a high-water mark that left no room to rise higher, and little possibility of sustaining the level Bush II had reached. By 2006 the GOP already needed a new map, and a new map also means a new ideology.

This article is in The Spectator’s inaugural US edition. Subscribe here to get yours.