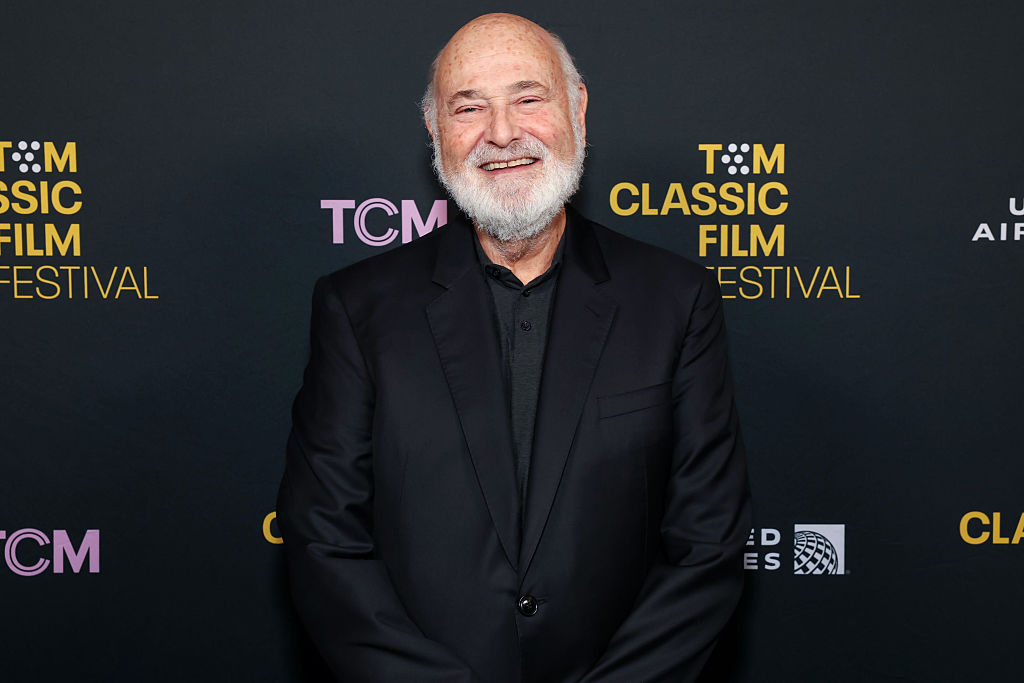

The death of the director and actor Rob Reiner in violent and unexplained circumstances is one of the most horrific and surprising stories to have emerged from Hollywood in living memory. One of the reasons why its elites live in areas such as Reiner’s exclusive neighborhood of Brentwood in California is precisely so that they will not be subject to the possibility of random violence in a way that less wealthy Americans face daily. Yet if news reports are to be believed, Reiner and his wife Michele were the victims of intrafamilial strife: a situation that all the gated walls and security cameras in the world could not ameliorate.

It is particularly ironic that Reiner met such a horrible end, stabbed to death in his own home, because the vast majority of the films that he made, especially earlier in his career, were infused with a sense of all-American joyfulness and hope that made him, for a while, a filmmaker talked off in the same breath as Frank Capra and Steven Spielberg. Son of Hollywood royalty Carl Reiner, he began his career as an actor, most notably in the role of Meathead in the Norman Lear sitcom All In The Family. It made him a household name, but also contributed to a sense of Reiner as a dumb, good-natured left-winger: he once remarked that “I could win the Nobel Prize and they’d write ‘Meathead wins the Nobel Prize.’”

It was in part in an attempt to escape from this straitjacket of typecasting that Reiner switched from acting to directing – although he continued to appear onscreen throughout his career, both in his own films and in those of others – and the first picture that he made was a particular triumph, in the form of 1984’s rock mockumentary This Is Spinal Tap. With a script that was co-written by Reiner along with its stars Christopher Guest, Michael McKean and Harry Shearer, it resulted in endless quotable lines – not least the description of an amp that “goes up to eleven” – and Reiner’s own performance as the hapless documentary maker Marty Di Bergi demonstrated his ability to play both warmth and uselessness on screen with great skill.

The film’s modest success led to a new and hugely successful second wind for Reiner, whose first seven films as a director represent one of the most interesting and accomplished runs of form that any 20th-century filmmaker ever managed. He excelled at romantic comedies, which included the John Cusack vehicle The Sure Thing and, of course, the peerless When Harry Met Sally, but his varied repertoire included everything from Stephen King horror (Misery) and swashbuckling meta-comedy (The Princess Bride) to all-American military courtroom drama (A Few Good Men). Another King adaptation, the coming-of-age drama Stand By Me, is commonly regarded as one of the seminal films of the Eighties, and his pictures made huge amounts of money at the box office.

Although Reiner never won an Oscar – he was nominated for producing A Few Good Men – and was probably, ironically enough, too versatile a talent to be seen as a true auteur, it was once a dependable badge of quality to see A Rob Reiner Film. He was also a skillful producer of high-end cinema through his Castle Rock production company, which was responsible for such modern-day classics as In The Line of Fire, The Shawshank Redemption and the loopy Malice, in which the Aaron Sorkin-doctored script allowed Alec Baldwin to declare, histrionically, “You ask me if I have a God complex? Let me tell you something. I AM GOD!“

Any suggestion that Reiner had traded his soul to anyone – be it a deity or a devil – to achieve success came crashing down with his first megaflop, the Bruce Willis family comedy North, which attracted bemused reviews and repulsed audiences. He rebounded with the Sorkin-scripted The American President, a slick, assured piece of entertainment that inadvertently led to The West Wing, but his directorial career never reached the same heights again. Instead, for the next three decades, he either made undemanding comedies or soft-focus issue dramas that played to his status as one of Hollywood’s premier liberal filmmakers.

The major exception was 2015’s Being Charlie, an unusually gritty drama about addiction and familial conflict that was explicitly autobiographical; it was co-written by his son Nick and was based on his life as an addict, as well as dealing with his strained relationship with his successful, distant father. The film was both a commercial and critical flop, and most journalists observed that there was a tension, both on and off-screen, between Reiner’s attempts to bring about reconciliation and a real-life happy ending for his troubled son, and Nick himself, who had clearly undergone experiences that no swell of orchestral music could compensate for. If reports of Reiner’s murder are accurate, then it will be this film – not this year’s lackluster Spinal Tap sequel, or indeed anything else in his great, distinguished career – that will be remembered, for all the wrong reasons. Which is an undeserved end to what was a fine life – right up until its horrific ending.

Leave a Reply