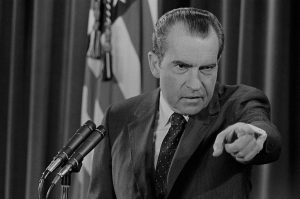

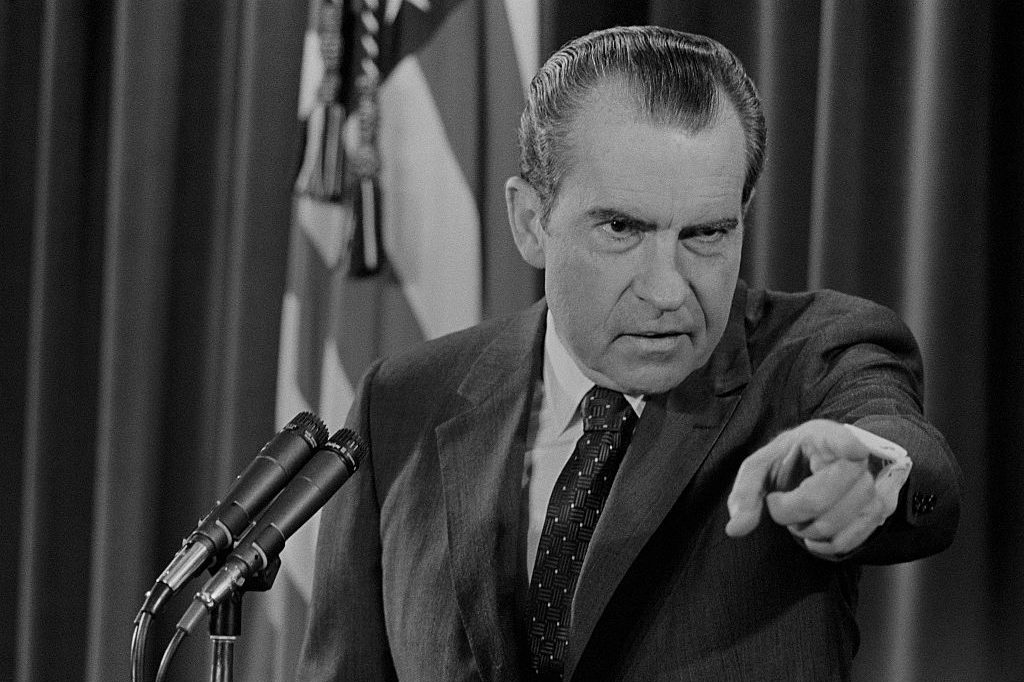

‘You gotta swallow this one, they stole it fair and square.’ That’s a Republican hack speaking to Richard Nixon, as fabricated in Oliver Stone’s 1995 biopic about our nation’s 37th president. The reference is to the 1960 election, in which Nixon’s opponent John F. Kennedy prevailed by 303 electoral votes to his opponent’s 219, although the popular margin was a scant 113,000, or about 0.16 percent, out of 68,837,000 ballots cast. Kennedy’s friend Arthur Schlesinger described him as ‘perplexed’ by the narrowness of his victory, and Harry Truman publicly declared himself ‘amazed’ (adding a choice intensifier or two in private) that the Democratic candidate should have failed to win the widely anticipated landslide against his smart and savvy but morally flawed GOP opponent. Sound familiar? Nancy Pelosi was perhaps being more insightful than she realized when said today that Biden would have a bigger mandate than John F. Kennedy. Or maybe she knew exactly what she was saying.

On Election Day, November 8, 1960, Nixon voted in his old hometown of Whittier, California, then climbed in a convertible with two friends and a lone policeman for company and drove across the border to eat Mexican food at a pavement café in Tijuana. Imagine that today. By the time they got back to Los Angeles at about 6 p.m., the TV networks were predicting a Democratic sweep. NBC confidently, and wrongly, told its viewers to expect a Kennedy victory in Ohio and California; in the end both states went Republican. In short order, Nixon also picked up the prizes of Arizona, Florida and Wisconsin. Just after midnight, local time, the New York Times went to press with the headline: KENNEDY ELECTED PRESIDENT. Within an hour, the paper’s managing editor Turner Catledge, worried that he had a ‘Dewey Defeats Truman’ fiasco on his hands, began hoping, as he put it in his memoirs, that ‘a certain Midwestern mayor would steal enough votes to pull Kennedy through’.

Enter the imposing figure of Richard J. Daley, then in the fifth of his 21 consecutive years as mayor of Chicago, although the word ‘mayor’ hardly does justice to a man whose political tactics would have raised murmurs of appreciation at a meeting of Mafia family heads. ‘By midnight on the west coast, we were getting good reports out of Illinois,’ Nixon’s press secretary Herb Klein remembered. ‘Then the Chicago precincts reported en masse and we were a little suspicious.’

When Nixon fell asleep at around 4 a.m., it was still anybody’s race. Two hours later, his 12-year-old daughter Julie shook him awake with the news that Illinois had been called for Kennedy by 8,858 votes out of 4.75 million cast. Nixon wrote in his memoirs, ‘There were stories of massive voter fraud in Chicago… The journalist and editor Benjamin Bradlee said that Kennedy had called Mayor Daley on election night to find out how things were shaping up in the city. “Mr. President,” Daley reportedly said, “with a little bit of luck and the help of a few close friends, you’re going to carry Illinois”.’

Nixon soon conceded the race with a congratulatory telegram to Kennedy, his surrogates fought on. The Republican National Committee filed a legal challenge to the Chicago results, only to see it dismissed by a Daley-connected circuit judge, Thomas Kluczynski, whom Kennedy duly promoted to the federal bench. Even so, a special prosecutor later brought charges against no fewer than 650 Illinois election officials. In 1962, three precinct workers pled guilty to bribery and corruption and served short jail terms. The Chicago Tribune was left to conclude, ‘The election was characterized by such gross and palpable fraud as to justify the conclusion that [Nixon] was deprived of victory.’

In Texas, meanwhile, Kennedy won by 46,000 votes out of 2.3 million cast. The candidate’s choice of Lyndon B. Johnson as his running mate, an act of political cynicism surely unparalleled until Joe Biden suddenly remembered his longtime admiration for Kamala Harris, now paid dividends in places like rural Fannin County, on the state’s border with Oklahoma. Despite having only 4,895 citizens on its electoral rolls, the county cast 6,138 votes, two-thirds of them for Kennedy. In one precinct in eastern Angelina County, Kennedy received 187 votes to Nixon’s 24, which was an impressive turnout for a community of just eighty-six souls.

If you removed Kennedy’s 27 electoral votes from Illinois and his 24 from Texas and awarded them to his opponent, Richard Nixon would have been elected president eight years earlier than he actually was, raising the possibility that we might now remember matters such as the construction of the Berlin Wall, the stationing of Soviet nuclear weapons in Cuba, and the escalation of the war in Vietnam in different terms.

Strangely enough, while Republican officials and others continued to vigorously dispute the outcome of the 1960 election, Nixon himself graciously accepted the inevitable. ‘We had made a serious mistake in not having taken precautions against [fraud], and it was too late now,’ he recalled, in another foreshadowing of events in 2020. Two days after the polls closed, the splendidly-named Sen. Thruston Ballard Morton of Kennedy flew to Key Biscayne, Florida, where Nixon had taken his family for a vacation, and urged him to challenge the results in Texas, Illinois, and nine other states.

‘Morton told him he thought the election had been stolen, and he ought to fight it,’ Herb Klein recalled. ‘Nixon sort of put him off. He listened and he said he’d think about it.’

Nixon later remembered that after Morton’s departure he’d sat alone for five minutes, reviewing the situation. It apparently took him only that long to come to terms with the declared result, which must have seemed at the time to be the death-knell for his political career. ‘A recount would require up to half a year, during which the legitimacy of Kennedy’s presidency would be in question,’ Nixon wrote. ‘The effect could be devastating to America’s foreign relations. I could not subject the country to such a situation.’ It was a dress-rehearsal of his ultimate resignation speech from the Oval Office 14 years later.

[special_offer]

Even then, certain Nixon allies failed to follow his example of putting country before political gain. The New York Herald Tribune’s Washington correspondent Earl Mazo, for one, spent much of the winter of 1960-61 in a personal crusade to ferret out cases of graft and corruption in Mayor Daley’s Chicago. ‘In one cemetery, I found the names on the tombstones of [people] who were registered and voted,’ Mazo recalled. ‘I remember a house. It was completely gutted. There was nobody there. But there were 56 votes for Kennedy in that house.’

A few days after Mazo began publishing his findings in the Herald Tribune, he received a call from Nixon inviting him to a meeting in his Capitol office. When he arrived, the journalist got the shock of his life. ‘He told me to kill the series,’ Mazo recalled. Nixon repeated his contention that the nation couldn’t afford a political crisis at a time of worsening relations with the USSR. ‘I thought he was kidding, but he was serious,’ Mazo wrote. Lest there be any doubt in the matter, Nixon also called the publishers of the Herald Tribune with the same message. They quickly killed Mazo’s story.

Nowadays the words ‘Richard Nixon’ and ‘probity’ might not marry as naturally as they should, but it’s possible that he took an altogether higher road in the immediate aftermath of the 1960 election than either of the two main contenders appear to have chosen for themselves today.