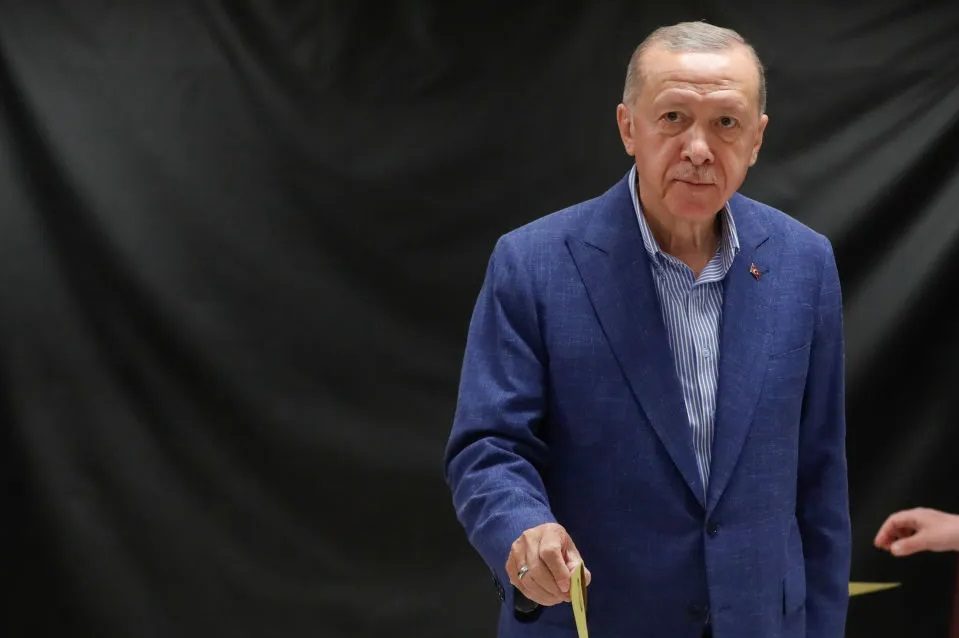

Today marks ten years since Recep Tayyip Erdoğan was elected president. There will be no celebrations and Turkish media may make little mention of the anniversary. The date is an important milestone, nonetheless, in Erdoğan’s remarkable career as Turkey’s most successful modern leader since the father of the nation, Kemal Atatürk. In the past ten years, Erdoğan overcame illness, a coup, social unrest and the hostility of several world powers to consolidate his iron grip on the country.

Before the 2014 election, the presidency was mostly a ceremonial role. Erdoğan came to power as prime minister in parliamentary elections in 2002 as head of the AK Party. The shift did not happen overnight. In 2018, the country switched from a parliamentary democracy to a presidential system through a referendum, but even before that, no one had any illusions as to who was calling the shots. The failed coup in July 2016 was a major catalyst.

Followers of the exiled cleric Fetullah Gülen are believed to have been behind the failed bid by a group of army and air force officers to take over the government. Three hundred people died. In the aftermath, Erdoğan lost no time purging every segment of society not only of the followers of his former ally, Gülen, but also of other oppositional elements. More than 160,000 public employees were fired and about 77,000 were arrested. The image Europe and the US once had of Erdoğan as a model democrat in the Islamic world was long gone.

“Democracy is not our goal but our vehicle to get there,” Erdoğan once said as mayor of Istanbul, a wordplay on the similar-sounding Turkish words amaç (goal) and araç (vehicle). Three decades later, there is little left of that vehicle besides its frame for appearances.

Elections are still held which are “free but not fair,” as observers from the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) put it. Wide-scale election fraud does not take place, but the independent press has been gutted and many opposition politicians are in jail.

At each election, he appeals to his traditional voter base, the central Anatolian religious conservative lower classes. In Erdoğan, they see a strong leader who dares to stand up to the West but at the same time makes them feel superior — not just to the dysfunctional states to the east but also to the West. “Europe envies us,” he often tells crowds and his supporters believe him.

At seventy, Erdoğan condemns western governments as hypocrites for their stance on Israel and human rights. At home, when a few hundred opposition protesters gather in Istanbul, whole neighborhoods are shut down and riot police outnumber protesters by at least three to one.

Since 2014, the police force has grown by 40,000, plus 30,000 loyal “neighborhood watchmen.” The prison population surged from 159,000 in 2014 to 348,000 in 2023 — by far the largest in Europe both in total number and ratio to population.

But there are signs that his model of governance is now in trouble. In local elections in March, Erdoğan’s AK Party lost all the major cities and came second for the first time since coming to power in 2002.

During the campaign period, Erdoğan said this would be his last election, as the constitution only allows two terms as president. But it would only take another referendum to change the constitution so he could run for a third term. Another option would be to call for an early election with a majority vote in parliament before his second term ends. 2028 is still far away.

As a young man in the 1970s, Erdoğan was prohibited by his father from pursuing a career as a professional footballer, despite an offer from Fenerbahçe, one of the country’s top clubs. “I’m glad my father, mercy be upon him, stopped me,” he said in an interview. According to the latest polls, more than half of the country would disagree.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.

Leave a Reply