On the day I arrive at the Suffolk County District Attorney’s office, DA Ray Tierney is off meeting with an unnamed witness in the Gilgo Beach serial killer case. In February 2022, more than a decade after police first recovered the remains of eleven victims, then-Suffolk County police commissioner Rodney Harrison announced the creation of a joint task force dedicated to solving the case. The task force, which included investigators from the DA’s office, quickly zeroed in on a suspect as they chased down a tip from a witness that hadn’t been properly investigated the first time around. Fifty-nine-year-old Rex Heuermann was arrested in July on murder charges and police have linked his DNA to several of the bodies. Tierney is personally leading the prosecution on the high-profile case, a rare move for a district attorney. When I finally get to sit down with Tierney, I ask why Heuermann was able to evade capture for so long.

“Because I wasn’t DA,” Tierney replies with a smirk.

We get a good chuckle out of it, but the truth is there’s probably little that goes on in Tierney’s office that he can’t take some credit for. He’s undoubtedly qualified for the role, with twenty-seven years of prosecutorial experience, including eleven as a federal prosecutor taking down MS-13 and prosecuting major drug, murder and white-collar crimes. Career prosecutor Allen Bode, a longtime friend of Tierney’s who now serves as chief assistant DA, says Tierney is “probably the best prosecutor on DNA evidence on the entire island” and that he’s “done every job in the office.”

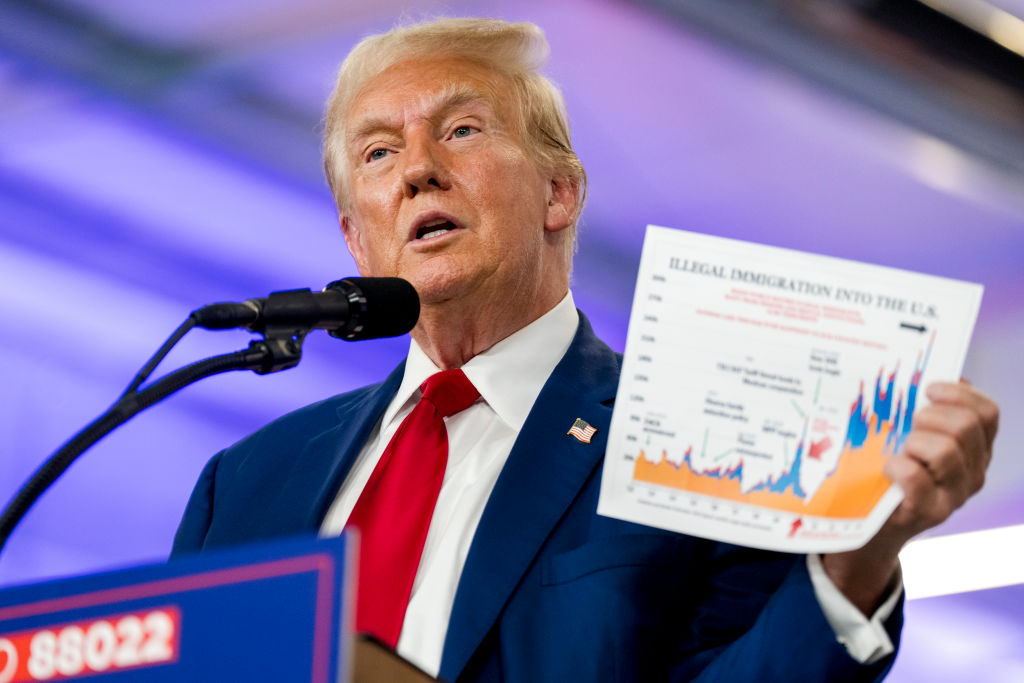

Frankly, although the Gilgo case is sensational, it’s not the reason I’m here. Tierney’s office is focused on law and order as many local prosecutors, their campaigns backed by Soros-funded organizations, take a progressive approach to justice that lets criminals off the hook at the expense of victims and other community members. Take Steve Descano, the commonwealth’s attorney in Fairfax County, Virginia, who twice released a man on gun and drug charges without bail. That same man later went on to allegedly commit second-degree murder. In the progressive prosecutor’s mind, though, criminals are frequently victims of generational poverty, gentrification, abuse, systemic racism or some other intangible that justifies or excuses their actions. The individuals who may become the victims of these criminals are merely collateral damage of achieving “equity” in the justice system.

Tierney decided to run for DA in 2021 in part because he felt DA Tim Sini was similarly selling out the Suffolk County community. Crime in New York had skyrocketed during the pandemic and Sini didn’t seem to be doing much about it. Tierney also viewed Sini as indicative of a larger problem in Suffolk County, in which he says “powerful people” effectively chose who was next in line for the role, qualifications be damned. Despite a lackluster track record as DA, Sini was being groomed by New York Democrats to run for Congress or county executive after his tenure. Sini initially supported state Democrats’ bail-reform policies and then conveniently flipped as crime spiraled out of control. He remained silent on proposed parole-reform measures.

“I was always a big critic of the system, and this is something my dad taught me: you’re allowed to criticize if you have no ability to change things. But the second you have the ability to change something and you don’t do it, you can no longer criticize,” Tierney says. “In the last couple of years, I saw that the district attorney’s office wasn’t really prosecuting cases. Nobody was going to jail. Cases were loading up.”

Tierney promised to get tough on crime and developed a sophisticated grassroots campaign, leaning on his local connections. Despite outspending Tierney by multiple factors, in November 2021 Sini lost re-election by fourteen points. In neighboring Nassau County, Republican Anne Donnelly bested favorite state senator Todd Kaminsky; the election of two Republican DAs in Long Island was a deep indictment of the progressive approach to crime being tested in New York.

“Suffolk County is very much like the biggest little town in America,” Tierney explains. “We live in the shadow of New York City. Why do you come out to Long Island? Why do you deal with the traffic and all the nonsense? Because you want your own little slice of the world. And so when you come out here, especially when compared to the city, you’re very concerned with quality of life.”

Tierney immediately set out to reform the office, bringing in his own team, separating the homicide and major crimes units (which had been combined by Sini) and creating a new bureau to tackle gun and gang violence and another dedicated to animal cruelty and environmental crimes.

One of his most popular initiatives was his plan to crack down on property crime, which he succinctly characterizes as “don’t steal other people’s shit.” New York’s laws don’t make it easy to put these people away, though. Shoplifters don’t get taken to jail; instead they get a ticket to appear. Unsurprisingly, plenty of offenders skip out on their court appearances. Tracking them down and trying to get a warrant takes a lot of manpower, so cases weren’t being resolved.

But “complex problems require creative solutions” seems to be a common axiom in Tierney’s office.

“We want to work hard, but we want to work smarter,” Tierney asserts. “A lot of prosecutors will hold up their hands and say, there’s nothing you can do. There is something you can do. It just takes a lot of work and it takes a lot of effort.”

In one case, his office followed a group of shoplifters to a pawn shop and through continued tracking of money and goods, plus a phone-tap warrant, they were eventually able to prove the thieves and the pawn shop were coordinating with one another. Tierney charged the group under organized crime laws to ensure they would be held pending bail and fully prosecuted.

“Thanks to our comprehensive investigation, we were able to bring Enterprise Corruption charges, which are more serious bail-eligible offenses, rather than simple larceny charges. Now, with these guilty pleas, we have ensured upstate prison time for the ringleader and pawn shop owner… and jail time for all his associates,” Tierney said in a statement about the case.

For simpler cases, Tierney set up a warrant squad to help funnel people who weren’t showing up for their court dates back into the system.

During my time at the office, Tierney meets with his retail theft task force, which coordinates with big retailers like Target, Ulta, Home Depot, TJ Maxx and Walgreens to hold shoplifters accountable. Many of these companies have been forced to leave cities like New York and San Francisco because of missing inventory and concerns for the safety of their team members. Here the retailers share names and surveillance video of repeat shoplifters and the DA’s office assists them with filling out trespass affidavits. When the thieves inevitably steal again, they are hit with felony burglary charges and held on bail awaiting prosecution. Tierney reminds the team that “we’re going to take this seriously,” and a team member confirms that retailers are “thrilled” with the help they’re getting from the DA’s office.

I’ve reported on crime pretty extensively the past two years, particularly in Washington, DC, where in 2019 the city council passed a bill that allows violent offenders under the age of twenty-five to receive early release without any judicial discretion regarding the offender’s level of remorse or the nature of the crime. But even I was surprised at the extent of soft-on-crime policies enacted in New York.

In 2018 New York’s Raise the Age law removed criminal responsibility for defendants under the age of eighteen, and the vague wording in portions of the law made it extremely difficult to prosecute any youth offenders, no matter how serious their crimes, in adult court. According to the Manhattan Institute, 83 percent of New York felonies committed by minors ended up in family court, including 75 percent of violent felonies. Family court records are sealed, so if defendants end up back in the system, judges cannot consider their full criminal history. In New York City, the law has led to higher rates of youth recidivism and a 200 percent increase in youth gun crime.

“Kids have basically become holsters for gang members,” Tierney explains. “If you solve the gun crime it traces back to the kid. And nothing can happen to the kids, so it’s the best thing possible for the gangs.” The statistics show, too, that once a kid has a gun arrest, they’re more likely to be involved in a subsequent shooting.

In 2021, Governor Kathy Hochul signed the Less is More Act, which effectively nullifies the penalties for most parole violations. Under that law, most technical parole violations — failing to check in with a parole officer, a positive drug test, or another violation besides the commission of a new crime — do not result in a parolee returning to jail. In 2023, Hochul signed the Clean Slate Law, which seals certain past criminal convictions from potential employers. New York state senator Dean Murray has pointed out that the Clean Slate law applies to “crimes committed against children (except sex crimes), assaults on police officers, manslaughter, gun felonies, domestic violence felonies, some terrorism offenses, multiple degrees of arson, [and] animal abuse.”

“People have a second start, which is fine,” Tierney argues, “but it’s not giving vulnerable communities the ability to make sure that they’re not allowing predators in their midst.”

The inclusion of manslaughter in the Clean Slate law is especially offensive to Tierney because, as he points out, manslaughter is often a charge used by prosecutors to ensure a conviction or plea from accused murderers. If the government elects to prosecute a higher charge, like first-degree murder, they can’t also charge second-degree murder or manslaughter. If the defense is able to successfully argue that the killing wasn’t premeditated, the alleged murderer gets off.

“A lot of prosecutors, myself included, hedge and we’ll let you plead to manslaughter,” says Tierney. “But you have to do twenty-five years, right? Well, now [under New York law] you can get out early and get that sealed, which is crazy.”

The state’s 2019 Domestic Violence Survivors Justice Act provides retroactive sentencing relief to offenders for whom abuse or trauma was a “significant contributing factor” to their crime. The law was mostly intended to help battered women who kill their abusive partners, but as Tierney points out, judges already have the authority to consider those circumstances when sentencing offenders. The new law instead seems intended to create sob stories for violent offenders to justify their crimes. Assia Serrano, who was released early thanks to the Domestic Violence Survivors Act, claims she was “coerced” by her childrens’ abusive father to rob an elderly woman she was taking care of. In the commission of the robbery, Serrano bound the woman, threw a coat over her head, poked her with a kitchen knife, and disconnected her phone and medical alert device. The woman died a day later from a blood clot stemming from the incident.

“There’s certainly a ratchet effect in New York laws. They keep proposing more and more laws that tilt more and more in favor of defendants. While each law individually is really bad, when taken as a whole, it’s a fucking disaster,” Tierney says.

New York is currently considering second-look reform, which would allow those who have been sentenced to ten or more years to apply for sentence reductions and parole reform. It’s targeted toward older inmates, typically — and logically enough — the ones serving the longest sentences for the worst crimes.

While Tierney tries not to let these laws stop him from prosecuting to the fullest extent possible, he also protests them. As he takes me through cases his office has worked on, Bode supplies me with the details. Quite a few of Tierney’s press releases on these cases openly criticize the laws that either allow someone out with no bail or place an arbitrary limit on their sentences. One points out that a fourteen-year-old who raped a woman while her four-year-old daughter watched can only be sentenced to a maximum of ten years. Another chastises a judge for allowing an arsonist out with no bail — she went on to rob a store at knifepoint two hours after her release.

“Criminals are not stupid. Criminals are impulsive,” Tierney says. “They’re so aware of where the line is.”

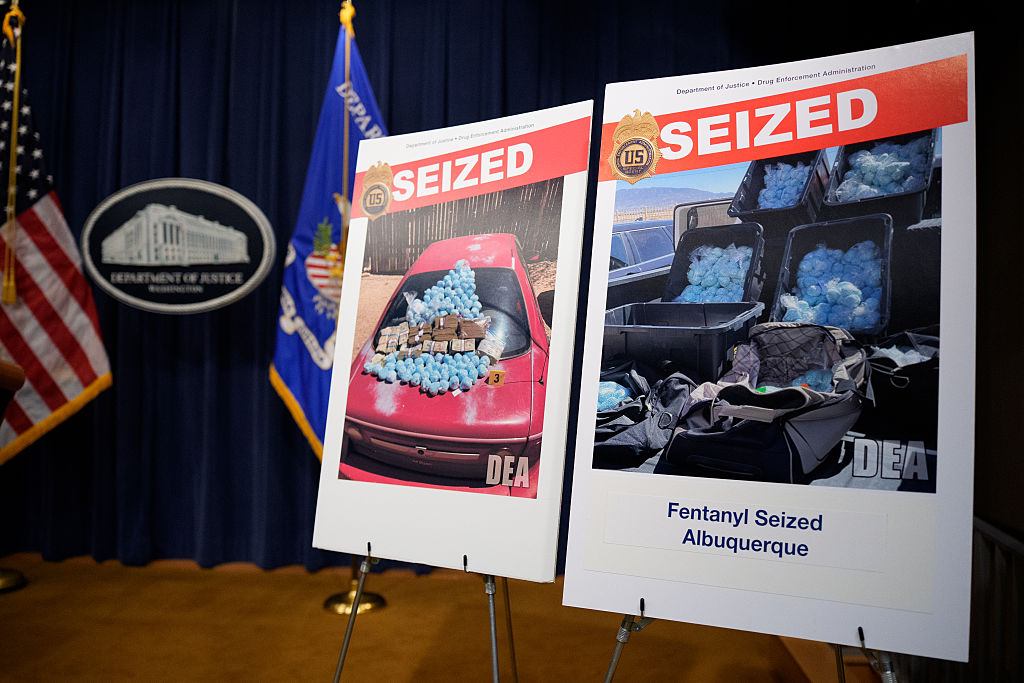

Take fentanyl dealers, who cannot be held on bail if they are caught with less than eight ounces — potentially lethal to thousands. Tierney is planning rallies in Albany, the state capital, to advocate for changing the possession laws, adding death-by-dealer laws, which hold drug dealers accountable when a buyer overdoses, and to ensure that families of overdose victims are eligible to receive compensation from the crime victim fund.

Tierney is not blind to the fact that his aggressive approach to prosecution can alienate communities which historically lack trust in law enforcement. ShotSpotter, a gunshot-detection technology that alerts police when shots are fired, has allowed police and the DA’s office to identify significantly more shootings. But during a meeting on the Shot-Spotter rollout, Tierney’s staff points out that a significant number of incidents reported by the technology are attributed by witnesses to “fireworks” or “car backfires.” This suggests witnesses are either covering for someone or just scared to talk to the police.

The office hired a community outreach director, Kimberly Jerideau, who partners with local groups to establish a positive relationship with the DA’s office and to find opportunities to educate vulnerable communities on how to protect themselves.

Tierney notes, “Every argument that you make for criminal defendants as far as racial disparities, well, those same disparities are reflected in the victims.”

His focus on the needs of victims of crimes is refreshing. Tierney asks the questions others seem to ignore: What is the impact of an annual parole hearing on victims who have to constantly relive the crime? How can victims truly get closure if there is no finality to the judicial process? Are we willing to lose the deterrence effect of punishment for bad behavior?

There’s not too much time for philosophy, though. Tierney shines when he’s working with the trial team preparing for a major burglary case or sitting down with the homicide bureau to go over active investigations.

Call it law-and-order, but really, Tierney is just doing the job.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s February 2024 World edition.

Leave a Reply