Sitting alone at the end of an absurdly long table or marooned behind a vast desk in a palatial hall, Vladimir Putin’s idea of social distancing has gone beyond the paranoid and into the realm of the deranged. His distance from reason and reality seems to have gone the same way. In little more than forty-eight hours, Putin’s sensible, peace-talking statesman act flipped into something dark and irrational that has worried even his supporters.

As Putin’s hour-long address announcing official recognition of the breakaway republics of Donbas went out on Monday, a producer on Kremlin-controlled TV texted me: “Boss okhuyel [the boss has wigged out].”

Indeed. Putin’s rambling and uncharacteristically emotional address to the nation and the bizarrely staged Security Council meeting that preceded it carried the distinct whiff of the dying days of the USSR. The ministers standing by to publicly agree (some more convincingly than others) with the boss; the formulaic tropes about protecting Russian-speaking people from “genocide”; the clichés about the “illegitimate” government in Kyiv. The spectacle resembled nothing so much as Leonid Brezhnev’s slurred 1979 announcement that the Soviet Union had to fulfill its “internationalist duty” to protect the people of Afghanistan.

How did Putin, the three-dimensional chess player whose cynical but often brilliant opportunism leveraged Russia from a middling regional power to world player, come to this? Covid distancing could have something to do with it. According to members of the Kremlin press pool, Putin’s paranoia over the virus has been extreme. He has forced everyone in his entourage to do frequent tests and pass through a disinfection tunnel at his Novo-Ogaryovo residence outside Moscow. The information bubble in which Putin — who famously doesn’t use a computer or the internet, which he considers a CIA creation — has lived for two decades has, over the past two years, become an echo chamber. His access to anything resembling a dissenting opinion has been more restricted than ever.

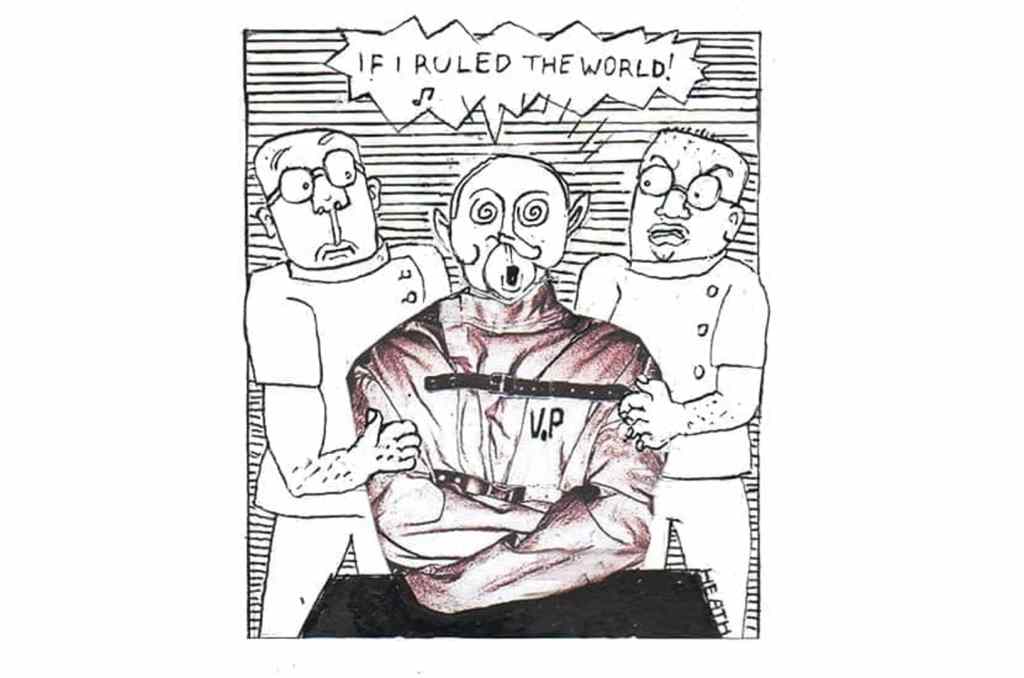

Just as significantly, Putin appears to believe his own propaganda. “He orders it up, then sees it come true on the screen,” says one Kremlin pool reporter who sees Putin on a weekly basis and confirms that the boss watches official TV news obsessively. “He’s his own director.”

The irony of Putin’s snap decision to recognize the breakaway republics is that up until that moment he had been doing so very well with diplomacy. Massive troop build-ups around Kyiv scared the world into finally taking his long-standing complaints over Nato enlargement seriously. On the eve of Putin’s recognition announcement, France’s Emmanuel Macron had proposed a summit with Germany’s Olaf Scholz and US president Joe Biden that would “define a new order of peace and security in Europe.” That’s exactly what Putin and his foreign minister Sergei Lavrov have been pushing for for months. The Kremlin’s official line, as recently as Sunday night, was that the Minsk peace accords should be implemented, leaving the Donbas republics’ voters inside Ukraine and its parliamentarians in Kyiv all pushing back against the Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelensky’s pro-NATO line.

So what changed so suddenly? As always, the Kremlin-controlled media is the bellwether of coming policy. Over the weekend, very amateurish fake footage of a series of supposed attacks by Ukraine on the Donbas republics was broadcast. Local leaders tweeted news of terror strikes that had not yet happened. Fake news has been a Russian speciality for years, of course. But “what’s surprising is they haven’t got any better at doing it,” Eliot Higgins, founder of the investigative site Bellingcat, told the Guardian. “In some ways they have got worse.”

That raises a question: who was the real target audience for this series of obviously staged charades? Credulous, older Russian TV viewers — or Russian TV’s most devoted viewer of all, Vladimir Putin? Putin is usually portrayed as an omnipotent master manipulator. But it’s also entirely possible that he is being manipulated by the many hawks in his entourage — notably defense minister Sergei Shoigu and Federation Security Council secretary Nikolai Patrushev. The Kremlin, as the Russians say, has many towers.

Ultimately we will never know exactly what prompted Putin to make his impetuous decision to recognize the Donbas republics. And then, two days later, to send in the tanks and bombers. There was a brief interlude that Putin, teetering on the very brink, still appeared to preserve the strategic ambiguity that has been the hallmark of this career. Was formalizing the presence of Russian troops in areas that had been de facto independent of Kyiv’s control since 2014 an actual invasion or not? The US said it was. The EU wasn’t so sure. The usual suspects — notably Hungary’s president and long-standing Putin ally Viktor Orbán resisted EU moves to impose sanctions. It was the last moment when the old, Machiavellian Putin, past master of divide and rule, was visible. Then he plunged on in a rain of fire and steel.

Putin evidently believes that his latest moves will pummel Ukraine into giving up its NATO dreams. From the outside, it would appear that he’s achieved precisely the opposite, pulling the plug on constructive dialogue and boosting support among ordinary Ukrainians for NATO and EU membership. Putin has jeopardized Russia’s main strategic hold over Europe — its dependence on Russian gas — as well as blown up the Minsk accords that he helped to author. Most worryingly of all, Putin’s invasion took even the members of his media and diplomatic apparatus completely by surprise. Russian TV propagandists were left scrambling to catch up with the new messaging that invasion was not western hysteria but policy. One senior Russian ambassador messaged me on the morning of the invasion to say “old strategy abandoned. No new strategy yet.”

Yet deep in his Covid-insulated echo chamber, this all apparently makes sense to Putin — and to the ultra-hawks who seem to have captured his ear. But his once razor-sharp sense of realpolitik has vanished down a rabbit hole of self-made delusion.

Now listen to Owen’s discussion with Chadwick Moore about Vladimir Putin on The District podcast. This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.