“Record drops in teen math and reading scores.” “National Math, Reading Scores Hit Historic Lows.” “Test Scores Flashing Red!” The headlines roll in weekly, each more alarming than the last. In February, twenty-six schools in Baltimore failed to bring a single student up to the most basic math requirements. The same month, sixty-seven schools in Illinois couldn’t produce a single proficient reader. We’ve reached a national education crisis, and its roots run deeper than many are willing to admit.

The pressing question is: why can’t America produce proficient students? But perhaps a more crucial question is: why can’t America produce proficient teachers?

The teaching profession has all the trappings of expertise: degrees, journals, a specialized lexicon and conferences. Yet, peel back a layer or two — and it’s like walking into a North Korean grocery store: what appears real is just spray-painted foam and cardboard cutouts. There’s no substance to the study of education. Without it, charlatans peddling false promises feast off our tax dollars while our schools wither. It’s a broken system.

I still remember the three years I spent thinking I’d become a teacher. I remember the die-cuts and the board decorating course. I remember the inane lectures on equity; the constant construction and reconstruction of something they called my Teaching Philosophy; I remember the IEPs and 504s and the bureaucracy of it all. But what I don’t remember is more important. I don’t remember studying the science of learning, or how the human brain picks up language, or what methods, tactics, and materials have been proven to help kids improve. I remember learning how to be a teacher, but I don’t remember learning how to teach.

And it’s not just me. A Chronicle of Higher Education poll revealed that a mere quarter of young teachers feel equipped to meet state standards. This lack of confidence is a symptom of a deeper issue: the absence of a solid foundation in the science of learning within the teaching profession.

A National Council on Teacher Quality study examined nearly fifty popular teaching college textbooks and found little discussion of proven methods. Instead, most texts promoted long-debunked teaching strategies, perpetuating a cycle of misinformation. As a result, as many as 97 percent of teachers continue to believe in myths like right- or left-brained learners and “learning styles,” despite overwhelming evidence to the contrary.

The gap between science and myth in teaching is vast — and nothing is being done to bridge it. Teaching colleges remain insular, rarely collaborating with fields like psychology, neuroscience, mathematics and biochemistry. As a result, only 17 percent of teaching colleges cover the fundamentals of reading —and fewer than half prepare candidates for STEM teaching. With the profession’s declining popularity, standards are becoming even more lenient.

Teaching colleges peddle myths and antiquated ideas with little opportunity for inter-departmental learning and there is little recourse but to soak it up and move on in hopes of filling in the gaps later.

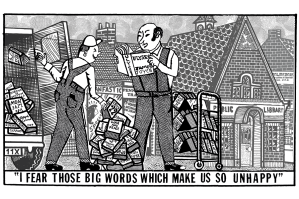

What does “later” look like? For teachers desperate for solutions, often struggling with the pseudoscientific methods they picked up at college, it means going to conferences, seminars and getting information from administrators and peers. Administrators and policymakers — hopelessly ill-equipped and with their feet to fire — are more than happy to dig further into their pockets to fund anything that resembles a solution. You can practically hear the vultures circling overhead.

The landscape of public education is littered with scavengers and their broken teaching programs, preying on the hopes and fears of hapless decision-makers. Just last year, our nation’s schools spent over $1.33 billion on reading programs, with junk science raking in the vast majority of that till.

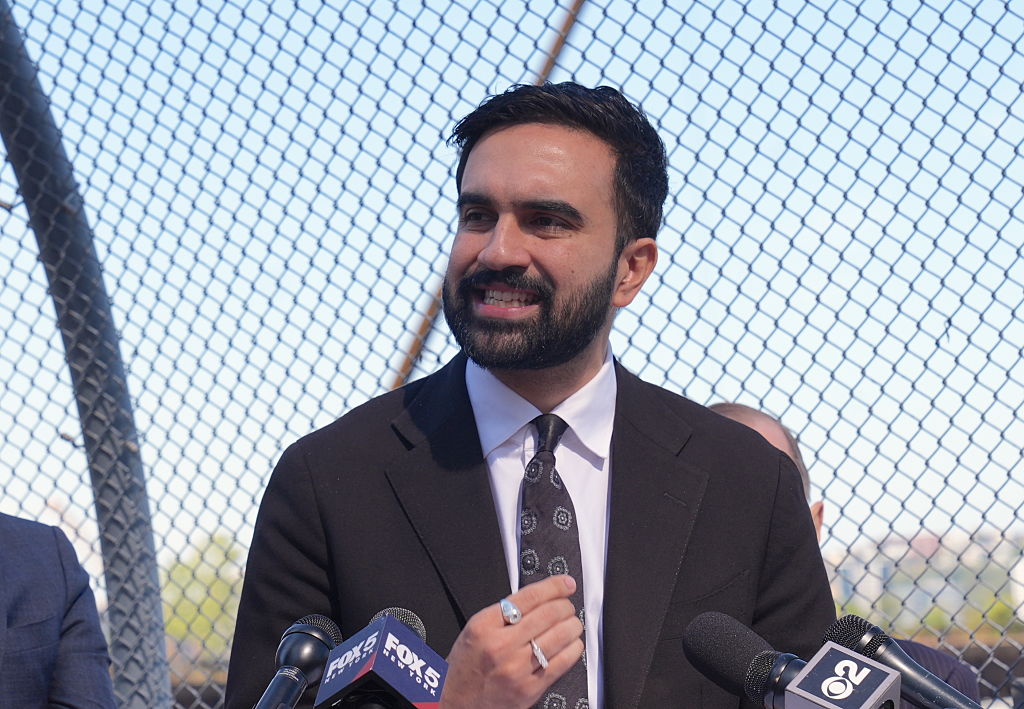

Lucy Calkins, a professor of education at Columbia University, created one of the nation’s most widely used reading instruction programs, “Units of Study.” It’s complete junk science. A groundbreaking report concluded that the program is deeply flawed and “would be unlikely to lead to literacy success.” The review criticized the program for its heavy reliance on the three-cueing system, a method that encourages children to guess words using pictures and contextual clues, a practice that has been proven ineffective by cognitive scientists. Calkins has siphoned millions of dollars from public education programs, and her program remains among the most popular in classrooms today.

Then there’s the duo Fountas and Pinnell, whose “Guided Reading” program has been debunked for lacking the systematic phonics instruction essential for early reading development. In fact, it has been reported that the program has been so poorly received in evaluations that independent reviewers failed to even include it in lists of reading strategies. Nevertheless, over a million teachers continue to use its products and strategies worldwide, generating over $60 million in any given year. The financial success of Fountas and Pinnell is a stark contrast to the educational outcomes of their program, highlighting a disturbing disconnect between profit and pedagogy in the world of education.

Everywhere you turn, these charlatans are knocking at the door vomiting out buzzwords and preying on the systemic ignorance of a broken profession. Whether it’s the faddy equity-based math in California or the newly popular Reading Recovery program, in education, snake oil is more prevalent than real medicine.

It’s a perverse cycle: underdeveloped teaching colleges produce underprepared teachers who are lured in by the promise of broken programs, only to find themselves trapped in a cycle of ineffectiveness. While our nation’s schools continually fail to teach the basics of reading and math, the purveyors of these programs laugh all the way to the bank.

It’s a system broken at every turn — and if we can’t fix it soon, we’re doomed.

Leave a Reply