‘During that time it seemed no easy thing to see any man on the streets of Byzantium, but all who had the good fortune to be in health were sitting in their houses, either attending the sick or mourning the dead… and work of every description ceased, and all the trades were abandoned by the artisans, and all other work as well, such as each had in hand.’

That’s a passage from Procopius’s History of the Wars, describing the way the bubonic plague ravaged Byzantium in 541 AD. If you want to feel historical time collapse, and the distance of centuries evaporate, it is worth reading the whole account. With some exceptions, there is little difference between the way governments in North America and Europe are handling COVID-19, and the way the Emperor Justinian dealt with the plague that struck his empire. (Justinian ended up desperately distributing free money during the crisis, which is not so different from the various magic money tree bailouts that have occurred in the past few weeks).

Lockdowns, quarantines, and isolations are the order of the day in the West, just as they were in Justinian’s time. Stay indoors, let the economy crumble, and pray. The outcomes are confusing and painful. In Italy, it’s likely we will never know the true death toll of the virus. In the UK, churches have shut their doors for the first time since the reign of King John over 800 years ago. The island kingdom’s one concession to modernity is the use of aerial police drones to bother dog walkers. In Spain, and elsewhere in Europe, doctors are using trash bags as shields. The glorious ‘imagine there’s no borders’ Schengen Area collapsed back into a patchwork of nation states in less than a week. More locally, the CDC remains perplexed about whether face masks are worth wearing. The overall situation is described, with some justice, by Bruno Maçães, as ‘medieval.’ Isn’t this supposed to be the ‘First World’, not Byzantium without the icons?

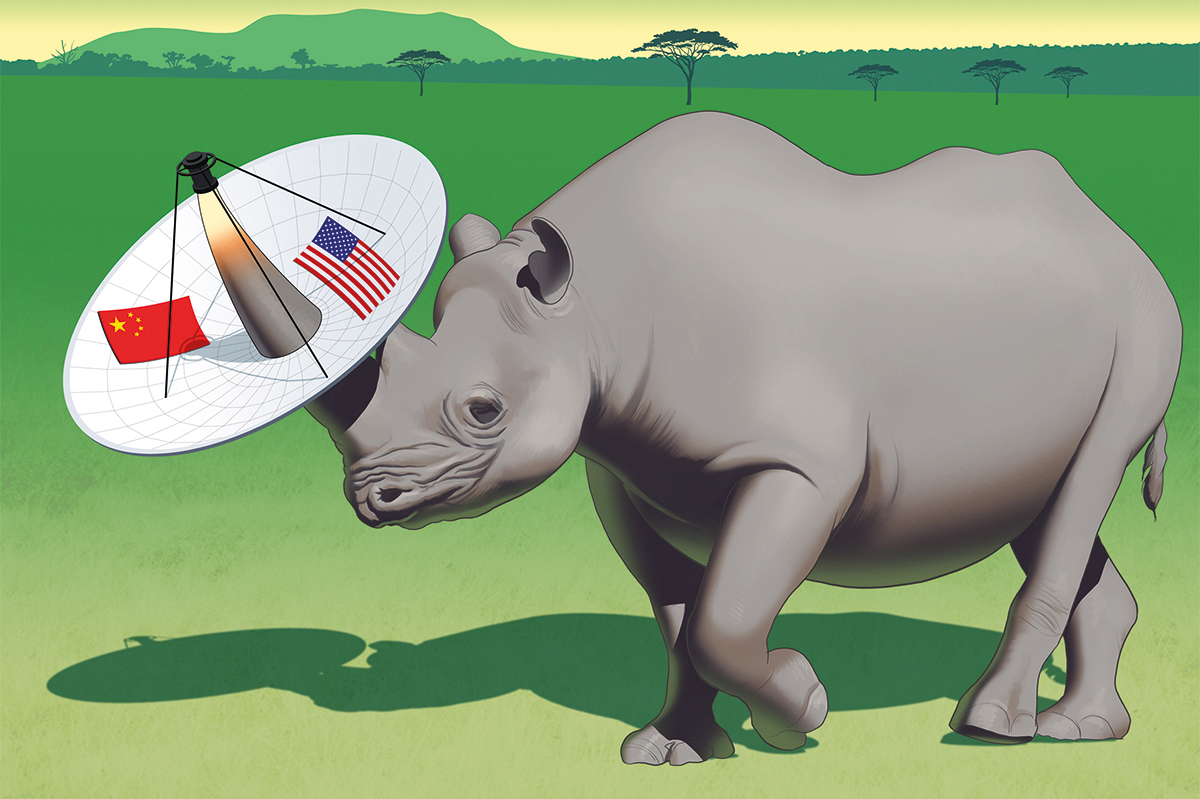

Of course, the major difference between our societies and the one Justinian ruled is technology. The Byzantines probably invented the pendentive dome; our technologists have access to unfathomable information-processing power. South Korea, China (if you trust their numbers), Singapore, Israel and Taiwan have leveraged this power to digitally monitor their populations, slowing the virus down without junking their economies in the process. Technology can be used to tell us where people are, where they’ve been and whether they have the disease. Data can be used to illustrate the spread of the disease. Contact between the infected and the as yet uninfected can be traced.

The fact that these solutions appear to work, or at least work better than Europe’s trash bags and good intentions approach, suggests that Silicon Valley will flourish in the Covidian Age. It’s the Valley, not a national security establishment that has spent years chasing Russians off Twitter, nor a president more captivated by viewing figures than ventilators, nor a press corps utterly preoccupied with racism, that has the tools, the know-how and the raw data to pass this test.

Big Tech may end up totally reversing its public image in the next few weeks. Valley companies are making websites to provide information on testing. They’re funding initiatives for vaccines. They’re providing housing for doctors and nurses, and funding to get medical equipment to them. Ideas and resources are being rapidly mobilized. Amazon, for better or for worse, is now the central actor in the economy. It drafted 80,000 new workers, cracked down on profiteers, extended grants to small suppliers and identified key goods. These actions, as one writer put it, have ‘the distinct flavor of government’.

If the Valley’s GPS technologies and invasive tracking tools turn out to be the magic bullets in this struggle, it will not be the first time in American history that private companies have vaulted a generational challenge. By the end of World War Two, the Ford Motor Company had built nearly 100,000 aircraft, more than half that number of aircraft engines, and thousands of generators. Industrial might, particularly in the form of bomber aircraft like those made by Ford, far more than boots on the ground, won the war. Afterwards it was the foundation of American hegemony for decades.

But just as running an empire comes with a levy of blood and treasure, so too might the Valley’s putative victory over COVID-19 come at a cost.

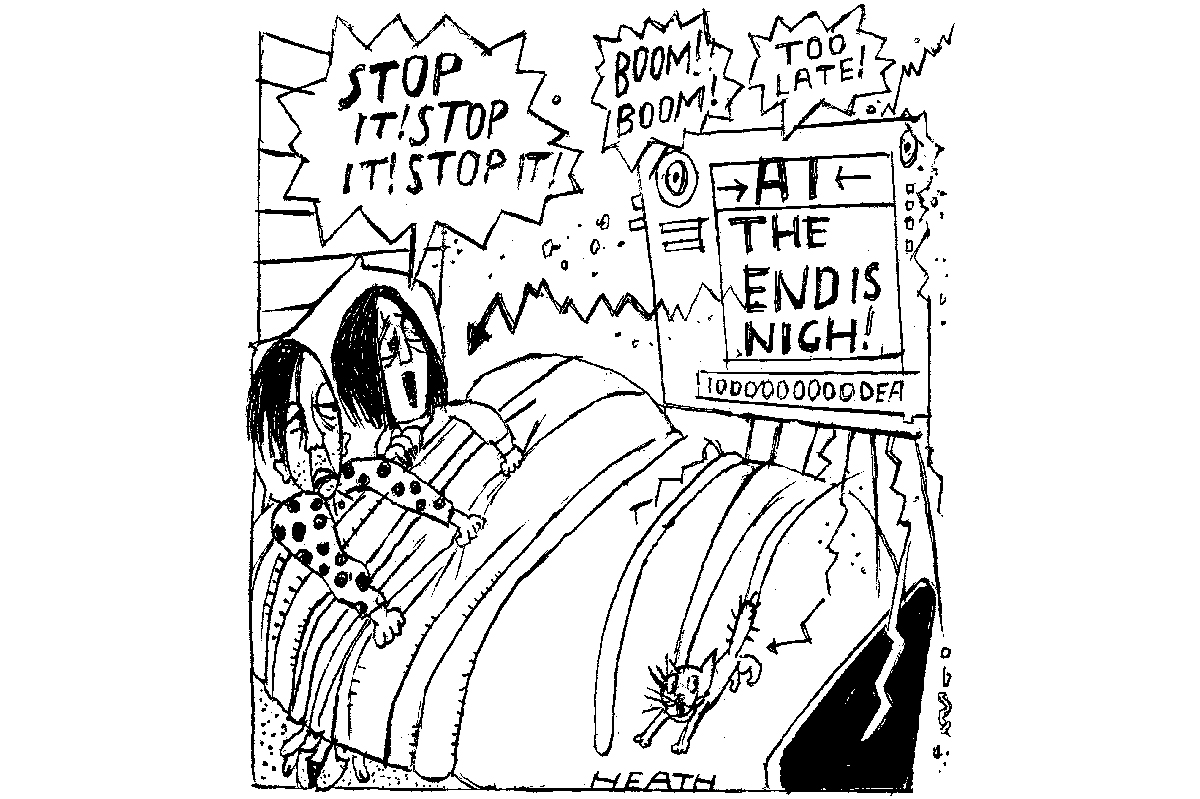

It is not as if criticisms of Facebook, Amazon, Google, Apple, Twitter and others, that were made on spectrum running from Elizabeth Warren to Josh Hawley, were without insight or accuracy. The notion that our screens knew us better than our families was fundamentally creepy. So was the evidence that Facebook, through freaky digital voodoo, could alter the emotional state of its users. The story about heavy internet users literally growing horns in their necks because how they interacted with their devices may not have been true, but it spoke to underground anxieties about the effect of over-mighty technology on the texture of everyday life. As does the burning down of 5G towers for fear they might spread COVID.

Privacy — which is not something anybody born after 1985 has ever truly experienced — was being dissolved in a sugar water of pornography, influencer posts and jackass tweets. Privacy was abolished in exchange for pig-satisfying amusement. Like the NSA, or like a tabloid journalist going through a celebrity’ garbage, Big Tech collected everything it could about its users.

Before the upheavals of 2016, an irresistible technological determinism seeped into the discourse. In the 19th century Karl Marx wrote that the hand-mill created the feudal lord and the steam-mill created the industrial capitalist. Now, in the 21st century, Yuval Noah Harari (every new religion needs a prophet) wrote about how smartphones created the new Big Tech overlords. Thanks to data, and the algorithms that collected it, overlord companies conquered the world. If this seemed sinister it wasn’t Mark Zuckerberg or Jeff Bezos’s fault. Most human beings, Harari said from his pulpit, ‘hardly know themselves at all’. The ignorance of the plebs became one of the greatest money-making opportunities of all time.

Now, in one of those infrequent but ironic summersaults of history, the suspicion of Big Tech that grew exponentially in the last four years is going to be benched. If privacy is what has to be exchanged for defeating the virus, or even staying entertained during lockdown, it seems to be a price fearful people will gladly pay. Technological determinism is back too. ‘There is no way,’ Maçães writes, ‘to stop technological progress’, especially given the demands of the Covidian Age. If that’s the case then the cost will be as bad as anything the virus does to us. Plagues destroy all forms of distinctiveness. So do technologies.