This article is in The Spectator’s January 2020 US edition. Subscribe here.

Galileo famously said that the book of nature is written in the language of mathematics. But what made him so important in the history of science was his further insight that mathematics, in order to reveal the laws of nature, had to be empirically tested. Mathematical formulae described what he thought would happen; he had to clamber up the leaning tower of Pisa and drop the two balls to convince us that objects of different masses fall at the same speed.

I am not sure that most modern pollsters have taken Galileo’s second insight fully on board. The modern pollster tends to be in love with his model. Hence his predictions tend to confirm the model rather than pull back the curtain on other contingencies.

There is a certain innocent pleasure in watching children intent on some game of make-believe. There they are, busily playing at cowboys and Indians (these are old-fashioned, unwoke children). They know what they are doing is not ‘real’. Nonetheless, they are utterly absorbed by the game. Many pollsters are like those children — with the difference that it is not always clear they understand their game is only a game.

I think of this every four years when the run-up to the American presidential election rolls around. Already, a couple of years out, polls multiply like mushrooms in a forest after rain. Of what use are they? The answer is that, as a predictive instrument, they are as valuable as a stopped clock.

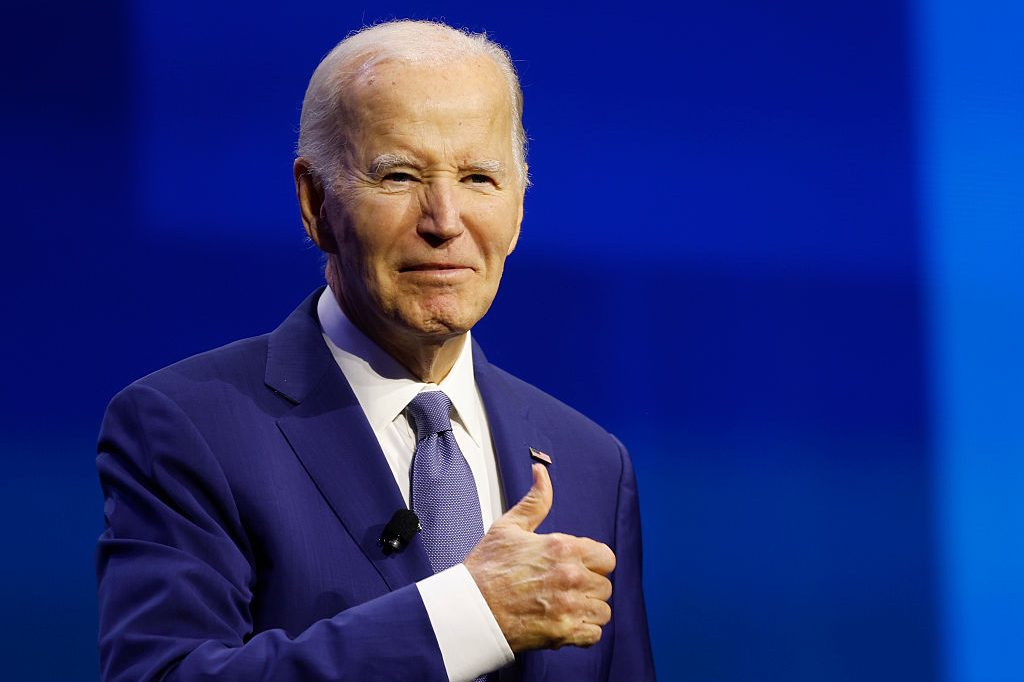

Even now, just shy of a year before election day, the polls are more static, more noise, than signal. Sitting here at the end of November, I search for ‘2020 General Election polls’. It doesn’t look good for Donald Trump. An NBC/WSJ poll taken just a couple of weeks ago has Joe Biden beating him by nine points. An ABC/WaPo poll is even scarier: Biden trumps Trump by 17 points. Fox puts Biden’s triumph at 12 points. IBD/TIPP and CNN drink from the same psephological trough: Biden comes out on top by 10 points for both.

What, so far away from the election, do all those numbers mean? If you are asking, ‘What significance do they have with respect to predicting the winner of the 2020 presidential election?’, the answer is nothing. They might have some significance as a barometer of public sentiment regarding Biden or Trump as of autumn 2019. But I am not even so sure how accurate they are about that. More likely such polls are indicative chiefly of the pollsters’ own prejudices.

There are several reasons for this — some to do with the quality and size of the sample. A big factor is time. A week, as Harold Wilson mournfully observed, is a long time in politics. Ten months is an eternity. So much can happen between now and November.

The BBC comedy show Yes, Prime Minister illustrated another important but largely unacknowledged reason for the uselessness of such polls as I have just cited. In one episode, Jim Hacker, the dim-witted PM, wants to reintroduce national military service. Why? One reason is that a poll reports it is popular. But neither the military nor the civil service favor the plan. What to do? Simple: commission another poll.

Bernard Woolley, Hacker’s private secretary, objects that a new poll will simply corroborate the findings of the initial one. The prodigious Sir Humphrey Appleby, the PM’s permanent secretary and the real power at Number 10, scoffs at such naivety. ‘Mr Woolley,’ he asks:

‘Are you worried about the number of young people without jobs?’ ‘Yes.’

‘Are you worried about the rise in crime among teenagers?’ ‘Yes.’

‘Are you concerned about lack of discipline in our schools?’ ‘Yes.’

‘Do you think young people welcome some authority and leadership in their lives?’ ‘Yes.’

‘Do you think that they respond to a challenge?’ ‘Yes.’

‘Are you in favor of reintroducing national service?’

As night follows day, the answer is yes. But the new poll Humphrey has in mind goes somewhat differently:

‘Are you worried about the danger of war?’ ‘Yes.’

‘Are you worried about the growth of armaments?’ ‘Yes.’

‘Do you think there is a danger in giving young people guns and teaching them how to kill?’ ‘Yes.’

‘Do you think it is wrong to force people to take up arms against their will?’

‘Yes.’ ‘Would you oppose the reintroduction of national service?’

How can Bernard say no?

I said that, at this point, polls for the 2020 presidential election are useless. But that is not quite right. There are polls and then there are polls. Any poll that proposes to say anything significant about the chances of Democrat X running against Republican Y is just a game. But there are other, more circumscribed polls that can tell us something about shifting allegiances and new voting blocks. Some of these, having taken the trouble to climb the tower and drop the balls, must give the eager prognosticator pause.

For example, were I a Democrat, I would be profoundly concerned by new polls from the right-leaning Rasmussen and the center-left Emerson. Both report that Trump’s support among black voters is around 34 percent. That is up from the usual Republican allotment of black votes in the single digits.

The rise is not surprising, exactly. Black unemployment is at historic lows, wages are rising and the effect of the endorsement of Trump by such pop figures as Kanye West cannot be overstated.

If that figure holds, and I think it will, or even rise further, then Trump (always remembering the Wilson caution) will not only win in 2020, he will win handsomely.

This article is in The Spectator’s January 2020 US edition. Subscribe here.