The details of engagements involving the head of MI6 are, unsurprisingly, usually kept secret. But not so Richard Moore’s meeting with the head of the Pakistani army, General Qamar Javed Bajwa. Officers from Britain’s intelligence service are also said to have met the Taliban, both in Kabul and Qatar. How do we know? Because hours after Moore met Bajwa, the news was plastered all over Pakistani media, much to the dismay and horror of British officials.

Pakistani leaders have spent much of the past two weeks basking in the Taliban’s triumph. Imran Khan lauded the Taliban for breaking the ‘shackles of slavery’. The Pakistani prime minister’s office made special social media banners to advertise calls received from world leaders, including Boris Johnson, in the wake of the debacle in Kabul. The Pakistan army’s public relations website even has an entire gallery dedicated to General Bajwa’s meet-ups.

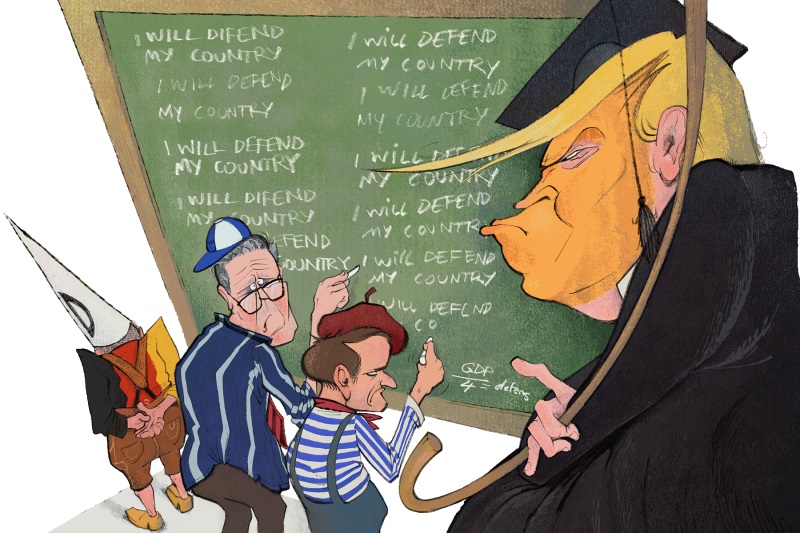

If it wasn’t obvious already, the Pakistani leadership wants to reaffirm that the Taliban’s rise to power signifies a win for its masochistic jihadist policy. The leadership’s loud advertising of Western officials, from defense secretary Lloyd Austin to Richard Moore, lining up for meetings in Rawalpindi’s army headquarters, is its self-aggrandizement as South Asia’s undisputed powerbroker. Whether they like it or not, Western nations are now looking towards Pakistan, not just to facilitate evacuations but also to shape the region’s future. All of this PR management is intended as a message for Joe Biden, whose delay in calling anyone important in Pakistan has been something of a sore spot for the egos of the country’s leaders.

Islamabad posing as the regional center of gravity is intended, too, as a warning for the Taliban, who have been cozying up to China, engaging with India, and facilitating jihadist groups that target Pakistan. Islamabad wishes to tell the Taliban leadership that despite their claims of having changed, the West trusts the Pakistan military to manage Afghanistan more so than any Afghan government.

The Pakistan military completed the Af-Pak border fencing the day before the Taliban took over Kabul. This timing was no accident: it served as a message for those in the West that Pakistan is on the frontline. Now more than ever, Islamabad has control over the volatile, and erstwhile porous, frontier. But is Pakistan’s increasingly important role in the Afghan debacle good or bad news for Western powers?

UK intelligence officials know full well that regardless of which version of the Taliban is in charge in Afghanistan, Pakistan’s army holds a huge degree of influence in the region. From Osama bin Laden to Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, high-profile jihadists have been found in Pakistan, both before and after the Taliban’s first rule in Afghanistan.

One of al-Qaeda’s leading masterminds Rashid Rauf orchestrated the 2005 London bombings and trained key operatives in Pakistan’s tribal areas bordering Afghanistan. In more recent times, Pakistan-based jihadist outfits that have long aligned with al-Qaeda and Taliban are now believed to be in the process of moving their strongholds to Afghanistan in anticipation of the next wave of global jihad. In a game of cat and mouse, the Pakistani intelligence apparatus is certain to be following suit; the Bajwa-led military establishment will be looking to relocate further assets to Afghanistan, which Islamabad has long treated as an extension of its own volatile tribal areas.

This is all part of a plan to convince the West that without the Pakistan army on board, peace in Afghanistan is impossible. Islamabad wishes to spread the fear — correctly or not — that if Pakistan doesn’t help out, Afghanistan will soon become a springboard for global terror. Of course, there is a slight problem with this narrative: if two decades and $2 trillion couldn’t bring any semblance of stability in Afghanistan with Pakistan ostensibly on board, how can the Pakistan military alone ensure that Afghanistan does not become a place that harbors terrorists?

For now, few are willing to ask this question. So despite vocal support for the Taliban, and brazen duplicity against the United States, it is clear that Islamabad is managing to blackmail Western powers. Will it succeed in continuing with this approach? It appears so. Whatever unfolds over the coming weeks, one thing seems sure: Western leaders meeting with the Pakistan army leadership are emboldening the military’s legitimacy as Afghanistan’s kingmaker.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.