Donald Trump is about to become only the third US president to be impeached —or charged with a crime — by Congress. The other two were Andrew Johnson, Lincoln’s successor, for firing his secretary of war in defiance of the House of Representatives; and Bill Clinton, for Paula Jones and Monica Lewinsky (technically for perjury and obstruction of justice). Johnson and Clinton were acquitted in their trials in the Senate, as Trump almost certainly will be too. And, as Johnson and Clinton’s impeachments just confirmed their supporters or opponents’ opinion of them, so Trump will emerge as exactly the person we always thought he was. But there may be surprises along the way.

The case against Trump is deceptively simple. He is accused of corruption, of extorting the Ukrainian government to give him something of personal value — an investigation into Joe Biden — in return for things in his gift as president: arms for Ukraine; an Oval Office visit for Ukraine’s leader Vladimir Zelensky. Trump’s former national security adviser John Bolton supposedly called this a ‘drug deal’; the Democrats call it an obvious case of soliciting a bribe and abuse of power: quid pro quo. The president’s defense will be that he had a ‘perfect’ right to ask for an investigation of Biden and that military aid was held up not because he was asking Zelensky for ‘a favor’, but because the Europeans weren’t paying their fair share.

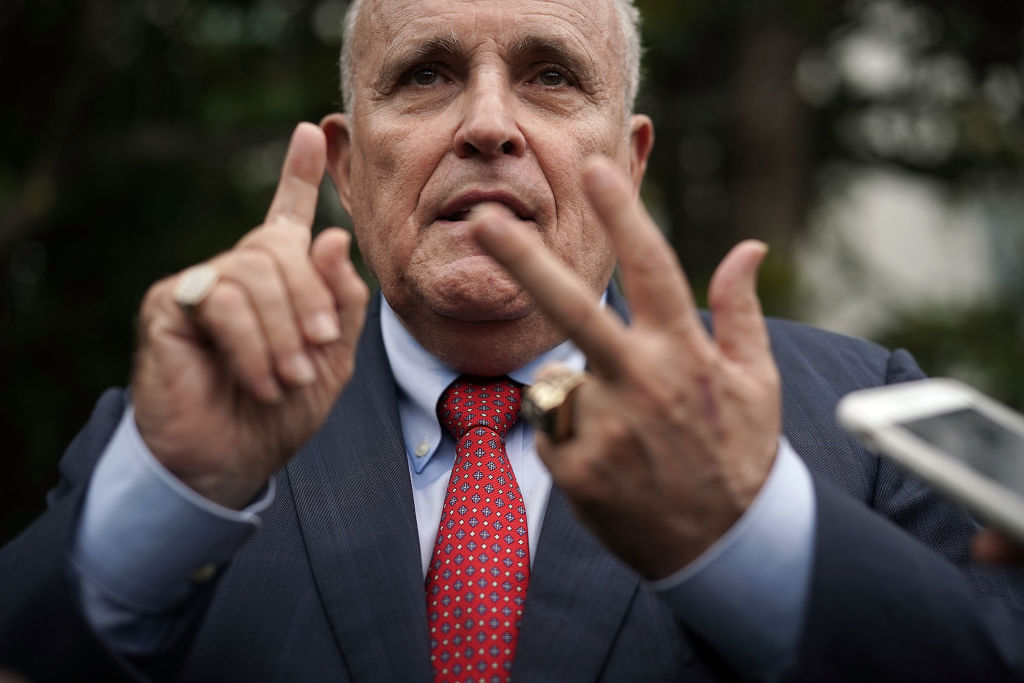

For the Senate, sitting as a jury, these issues are relatively straightforward. It’s when we come to the role of Trump’s personal lawyer Rudy Giuliani that we enter a quickly darkening thicket. Giuliani ran the operation to find dirt in Ukraine on Biden and his son Hunter, who did business there. Judging from the volume of leaks from the Southern District of New York, Giuliani is under intense scrutiny by prosecutors trying to establish if what he did in Ukraine broke American law. He hasn’t responded to my questions — and nor have his lawyers — but he’s always denied doing anything wrong: ‘You can knock yourself out looking at everything I do and I do not break laws.’

The fate of Michael Cohen, now a resident of Otisville Federal Correctional Institution, shows the perils of being Trump’s personal attorney. Cohen had to get a mortgage — and lie on the application — because Trump did not provide the money to silence Stormy Daniels (the porn actress who said she’d had an affair with Trump, in case anyone has forgotten). Cohen’s lie about the mortgage gave the FBI leverage against him, especially as his wife had co-signed the paperwork. He was forced to admit that his pay-off to Stormy amounted to an illegal campaign donation. As with Cohen, it’s important to know where Giuliani got the money to fund whatever it was he did for Trump in Ukraine.

Giuliani has tweeted to deny that he’s ever ‘taken a penny’ from Trump himself. He says he works for Trump pro bono. That’s a legal arrangement for a lawyer and a President-in-Office, but it’s also very unusual. Someone familiar with many of the players in Ukraine told me of wild rumors that Giuliani had spread half a million dollars around Kiev to pay for information. My informant added that people were busily forging documents to fit what they thought the president’s lawyer would want (though they were not doing this at Giuliani’s behest). Even if these rumors are false — and Giuliani would no doubt deny them — the Ukrainian operation must still have cost an oligarch’s ransom. What was Rudy getting out of it, apart from the honor of protecting his friend the Commander-in-Chief? Is it possible that while talking to various Ukrainians as the president’s unofficial envoy, he was also doing business for himself?

Giuliani’s tweet says he never tried to ‘enrich himself’ in Ukraine. But a source in Kiev told me that Giuliani or his associates had tried to get a deal involving Naftogaz, Ukraine’s national oil and gas company; a story later aired by CNN after a leak from the Southern District. The same source then told me that there had also been negotiations for a Trump Tower in Kiev. The Trump Organization did not respond to my questions about this. It is an explosive story, if true.

According to the New York Times and the Washington Post, Giuliani tried to obtain a contract for $200,000 to represent Ukraine’s prosecutor general, Yuriy Lutsenko. Giuliani says the deal never went ahead. Certainly Lutsenko seemed unhappy when Giuliani & Co. told him he’d have to pay another fat fee to their preferred lobbying firm for a meeting with the US Attorney General. Showing a better grasp of American slang than of American politics, Lutsenko told the Post: ‘I said that I am the prosecutor general of Ukraine and will not pay a dime.’

Leave aside for a moment the pleasing irony that Giuliani was investigating Hunter Biden for taking money from Ukrainians while himself negotiating to take money from Ukrainians. Lutsenko supposedly had information on Hunter but he also seemed to want — for his own reasons — to get the White House to fire the American ambassador in Kiev, Marie Yovanovitch.

Trump criticized Yovanovitch in his call with the Ukrainian president, saying ‘the woman was bad news’. Did Giuliani influence Trump? And was Giuliani influenced by the Ukrainians he was courting? This might be why there are reports that he’s being investigated for the federal crime of being an unregistered agent of a foreign government.

I met Yovanovitch briefly in Kiev in the summer of 2017. I’d been told by a former senior official at one of Ukraine’s many intelligence agencies that the US embassy had secretly helped to make public the page from the ‘black ledger’ that brought down Trump’s campaign manager Paul Manafort in 2016. This seemed ridiculous: embassy staff could have been flouting the Hatch Act, which makes it illegal for employees of the federal government to interfere in US elections. Still, I asked the embassy for a meeting with Yovanovitch, telling her press officer exactly what I wanted to discuss. Astonishingly, they agreed.

A few minutes after sinking into one of the deep sofas in the elegant, white stucco residence in Pokrovska Street, it was clear that someone had blundered. When I asked Yovanovitch what she knew about Manafort, the temperature in the room dropped ten degrees. The press officer looked at his shoes. The ambassador quickly brought the interview to an end, but as I was leaving, she said she wasn’t surprised by what I’d heard. ‘They think the US embassy is behind everything that happens here.’ She was, it turned out, a cautious State Department bureaucrat, not a fanatic running an operation to bring down Trump from the embassy in Kiev. But that’s the story that Giuliani and Trump have been sold. Today, Yovanovitch blames this ‘smear campaign’ on her efforts to help clean up Ukraine, which she said had made enemies of some powerful figures ‘who preferred to play by the old, corrupt rules’.

Lutsenko’s motives for wanting to remove Yovanovitch are opaque, but she had criticized his efforts to fight corruption, telling him to concentrate his investigations in his own office. The fact that one of his deputies was in charge of the file on Hunter Biden’s business dealings in Ukraine will only add to Trump’s suspicions. It’s more than likely, though, that the only reason there was a Biden file in the first place was to curry favor with the White House and neutralize an embassy that was being all too effective.

Lutsenko has now resigned as prosecutor general and is himself under investigation for corruption. Whatever the truth of those allegations, Giuliani was perhaps fortunate not to have taken him on as a client. Yet in his campaign against the ambassador, Lutsenko is said to have found common cause with two Soviet émigrés who were clients of Giuliani’s: Lev Parnas and Igor Fruman. They are now charged with making an illegal donation of $325,000 to a pro-Trump superpac, America First Action — a charge they deny.

Where would Parnas and Fruman get such money? One possible answer — and it’s not a good one for either Giuliani or Trump — is that they got it from Dmitry Firtash. Firtash is one of Ukraine’s richest men, said to be worth tens of billions of dollars, but he is under house arrest in Vienna, fighting extradition to the US and protesting his innocence of all charges. There’s a case against him in Chicago, where he’s accused of directing a conspiracy to pay $18.5 million in bribes to Indian officials for permits to mine titanium for Boeing. Firtash is known for his impeccable tailoring and opulent lifestyle. A leading Ukrainian politician once told me that to understand Firtash you had to know that luxury was of supreme importance to him. He would do anything to avoid seeing the inside of an Illinois jail cell. So it would be no surprise if Firtash has inserted himself into Trump’s apparent hunt for kompromat on the Democratic frontrunner.

Firtash gave an interview to the New York Times with the purpose of denying that he’d paid for Giuliani’s Ukraine operations. He ended up confirming that he’d given large sums to Parnas, handing over a $200,000 ‘referral fee’ for finding him new lawyers in Washington, DC. These lawyers turned out to be the husband and wife team of Joseph diGenova and Victoria Toensing, who — as their spokesman told me — have been friends with Giuliani ‘for 40 years’.

Their spokesman told me that Parnas had been paid through the law firm as a ‘consultant and translator.’ According to CNN, he joked that he was ‘the best-paid interpreter in the world’. CNN said that before meeting Firtash, Parnas was so hard up he couldn’t even pay for his son’s bris (circumcision). Afterwards, there were private jets, bodyguards, and an entourage traveling in a convoy of plush new SUVs.

Where did this money — Firtash’s money — originally come from? He was a fireman in Soviet Ukraine but his fortunes began to change when he opened a business to export canned food. A US diplomatic cable published by WikiLeaks said he did this under the patronage of Semione Mogilevich, one of the Russian mafia’s most feared leaders. According to this same cable, Firtash told the US ambassador in Kiev that he was forced into this arrangement. However, when he went on to found Ukraine’s biggest gas company, RosUkrEnergo, he was accused in Ukraine of being Mogilevich’s frontman — with Mogilevich running it for the Kremlin. A former Ukrainian prime minister, Yulia Tymoshenko, told the BBC she had ‘no doubt’ that Mogilevich and ‘some powerful criminal structures’ were behind RosUkrEnergo. The indictment in Chicago says Firtash ‘has been identified by United States law enforcement’ as an ‘upper-echelon associate…of Russian organized crime’.

I was able to read some reports on this by Robert Levinson, a former FBI agent who was obsessed with Mogilevich and probably knew more about him than anyone in the US government. He describes a scheme under which Firtash’s business bought gas cheaply from the Russian state company Gazprom and sold it to Ukrainians expensively. Levinson believed that the difference in price allowed for a skim of more than a billion dollars a year — and that this money was used to bribe politicians in Ukraine. He has since gone missing in Iran but his reports depict a flood of dirty money washing through every corner of Ukrainian politics, the sluice gates ultimately controlled by Vladimir Putin.

Firtash denies all this, telling TIME magazine a couple of years ago that Mogilevich was ‘never my partner’. And diGenova and Toensing’s spokesman says they were not funneling either money or information from Firtash to Giuliani.

Giuliani-diGenova-Toensing-Parnas-Fruman-Firtash: despite all the denials, the relationships among this curious group remain unclear. The Democrats would certainly love to show that the money for Trump’s Ukrainian operation ultimately came from the Russian mafia and the Kremlin.

But could someone else entirely have been Giuliani’s hidden benefactor? Two sources mentioned a new name: Oleksandr Onyshchenko. Onyshchenko is another oligarch on the run. He is accused of embezzling $80 million from a Ukrainian state-own gas production company, but says that these charges were politically motivated because he had fallen out with Ukraine’s president at the time. He has published a book in which he alleges that his job in the Ukrainian government was to pay bribes to members of parliament. In a neat coincidence, he claims that $2.5 million was paid to get parliamentary approval for the appointment of Yuriy Lutsenko, the prosecutor general who later spoke to Giuliani. ‘Money was carried out in black duffle bags through the narrow elevator in the lounge of the president’s Cabinet room.’

I met Onyshchenko, who is a former Olympic showjumper, earlier this year at a riding club in a sunny resort somewhere beside the Mediterranean. Since then, I’ve spoken to him by phone. He confirms that he met Giuliani to ‘offer help and information’ on the Bidens. I haven’t been able to reach him to ask if he was also employing Giuliani as his lawyer, as my two sources maintain. He was arrested in the German city of Aachen on December 6, so we may have to wait some time for his answer. Giuliani has not responded to calls either but he has always denied that his efforts to help the president were paid for with foreign cash, whether from Firtash or anyone else. The Democratic prosecutors at Trump’s Senate trial will try to prove that wrong.