The coronavirus crisis has exposed Europe’s varying attitudes to state intervention and individual liberties. It has revealed just how different the continent’s countries are. While there is some convergence around the policy of self-isolation, there is a divergence in the level of gusto with which governments are implementing this policy. The reluctance Boris Johnson has shown in coercing the British people into lockdown reflects his, and the country’s, libertarian instincts. State control is understood to be something that is to be used as sparingly as possible. This contrasts with more statist countries which appear only too eager to crack down, and their people, who appear only too willing to tolerate this state crackdown.

In this way, coronavirus has revealed Europe as a place in which each country fends for itself. Differences between the European countries may at first glance appear subtle, but their instincts are poles apart. France’s Macron seemed all too keen on the outset of the prospect of a lockdown and the suspension of social life, setting the scene for mounting tensions between the state and the people.

Some will dismiss any civil liberty concerns, pointing out that countries such as the UK are falling into line by dropping the original ‘herd immunity’ approach. Yet this misses the point. The reluctance with which Britain has moved towards lockdown is an affirmation of the country’s democratic instincts. ‘The fact that there’s somebody in No. 10 who feels hesitant about taking these powers, hesitant and reluctant to order people to change every aspect of their lives has got to be a good thing’ according to Guto Harri, a former adviser to Johnson. The BBC’s Nick Watt describes Boris Johnson as ‘a libertarian who recoils at the idea an overbearing state’. His first instinct is to treat the British people as grown-ups and persuade them rather than order them around. Like a benevolent headmaster he warned Brits that if they congregate in close proximity in parks and on beaches, he would be forced to send them to detention.

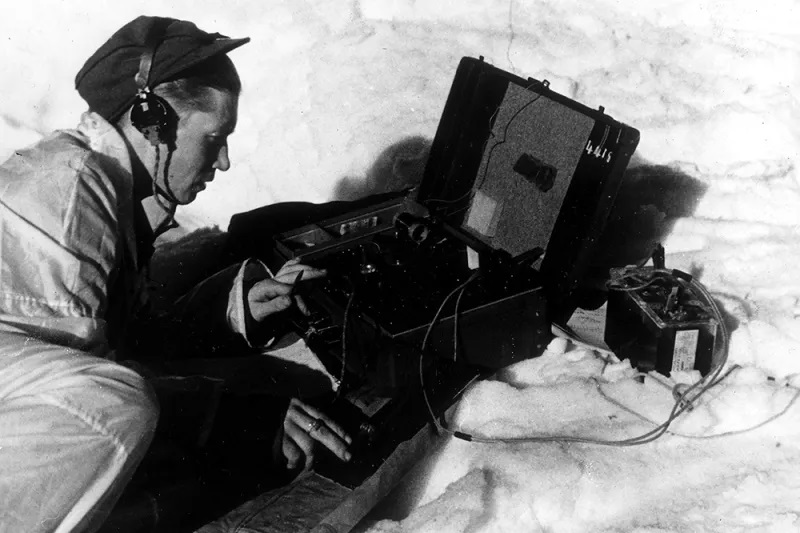

Then there are countries that believe passionately in democracy, but also trust deeply that the state will look after their best interests. As he handed a warship to the Norwegians in 1942, Franklin D. Roosevelt famously said ‘if there is anyone who still wonders why this war is being fought, let him look to Norway’. Now, nearly 80 years later, this new war provides insights on Norwegian attitudes to civil liberties. Norway, a country of five million, has accepted ever increasing curbs on freedoms not seen since the German occupation.

The country’s center-right coalition government is introducing measures that are of a similar severity with those of a war-torn country. This month a bill — the ‘corona law’ — was passed in parliament. It states that for one month, the minority government has been granted increased powers in order to govern effectively. The coalition, consisting of Høyre (Norway’s center-right Conservative party), Venstre (a socially liberal party) and Kristelig Folkeparti (a center-ground Christian people’s party), had tried to make the new law even more far-reaching — some would say illiberal — attempting to gain six months of direct rule.

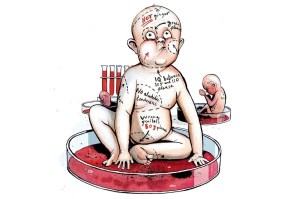

As in Asian countries, these hardline policies may be vindicated by data showing a moderating number of new cases and a minimal number of deaths. But whatever ‘the end’, it is hard not to feel unsettled watching a government imposing its will and a people blithely accepting it.

Do Norwegians secretly hanker after harsher medicine from the powers-that-be? ‘It’s a kind of protestant heritage that the worse the medicine tastes, the better it works,’ tweeted Kristian Gundersen, a professor of biology at the university of Oslo. Anyone who has visited Scandinavia will have felt the expectation that rules are observed. While this helps minimize crime levels, there is a darker side to this self-policing society; reports of people calling the police to report neighbors they perceive to be breaking the rules, public shaming on Facebook groups of joggers allegedly not keeping enough distance to others, and suggestions of ‘look to China’ and other totalitarian regimes. It seems many are willing to jettison democratic principles at the altar of combatting the pandemic.

When democratic principles are disregarded in other countries, Norwegians are usually the first to criticize. Norway is held up as the world’s best democracy by the Economist intelligence unit’s democracy index. Yet in this COVID-19 world, politicians are quick to forsake these democratic traditions. It was a stroke of irony that Norway’s far-left parties, with totalitarian tendencies of their own, helped temper the severity of this new law. The new restrictions severely curb the free movement of Norwegians. Along with the closures of schools, restrictions on cafes, restaurants, the closure of most shops and a ban on gatherings, a new ban on visiting cabins and second homes, citing undue pressures on local health services, will see Norwegians fined heavily or put in prison for 10 days if they disobey. That will be a bitter pill to swallow for the owners of the 438,000 cabins dotted around Norway’s mountains and coastline. For many, the cabin feels more like home than their main address. It is not just central government that is taking control; local councils are also coming up with their own local laws. These include forcing outsiders to quarantine for two weeks and threatening two years in prison for people who hug or shake hands.

As the data demonstrates that Norway is getting a grip on the virus, regulations should in time be eased. There is a glimmer of hope for those Norwegians who were looking forward to cross-country skiing expeditions at Easter, complete with oranges and Kvikk Lunsj (Norway’s answer to Kit Kat). Dr Preben Aavitsland of the Norwegian institute of public health (NIPH) has suggested that it might even be useful to disperse Norwegians in the vast Norwegian mountains, in order to avoid crowded city parks.

In the UK, Boris’s agonizing over the trade-off between freedom and wider restrictions was clear as he moved towards the latter this week: ‘No prime minister wants to enact measures like this. I know the damage that this disruption is doing and will do to people’s lives, to their businesses, and to their jobs,’ he said solemnly, announcing a three-week lockdown.

By expressing sentiments that resonate with British instincts, Boris is carrying his people with him while imposing unprecedented restrictions. Across Europe, the state is reaching further into every aspect of people’s lives. What will define this period depends not only how our governments behave, but also how we as individuals respond.