California’s derelict legions are everywhere — under bridges, near railroad tracks, blocking off-ramps and weaving unsteadily across busy avenues on bicycles.

The soft-woke rich can no longer hide in luxe enclaves. Taxpayers are fleeing the troubled state, hundreds of thousands of them since 2020. California’s fabled quality of life is taking a rapid dive, yet the cost of housing, already outlandish, goes up and up.

Five years ago, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals upheld Martin v. Boise, declaring that municipal laws, “prohibiting sleeping outside against homeless individuals with no access to alternative shelter,” violate constitutional protections against cruel and unusual punishment, thus voiding local vagrancy laws.

To radical jurists and many leftists, open drug markets and madmen roaming city streets provide living tableaus of America’s moral ruin. Any condemnation of the raggle-taggles is blaming the victim. No stigma allowed: compassion is spoken here. “What are you going to do, shoot them?”, progressives ask critics scornfully, closing the conversation with a thud.

Martin v. Boise is no doubt a spurious use of the eighth amendment. Yet in 2019, the Supreme Court — it remains a mystery why — declined review. Since then, judges in California and elsewhere have willfully used the case to tie up even modest efforts at remediation and removal of tent encampments, most spectacularly in San Francisco and Portland. Grants Pass, Oregon, has recently petitioned the Supreme Court to hear and possibly reverse the precedent.

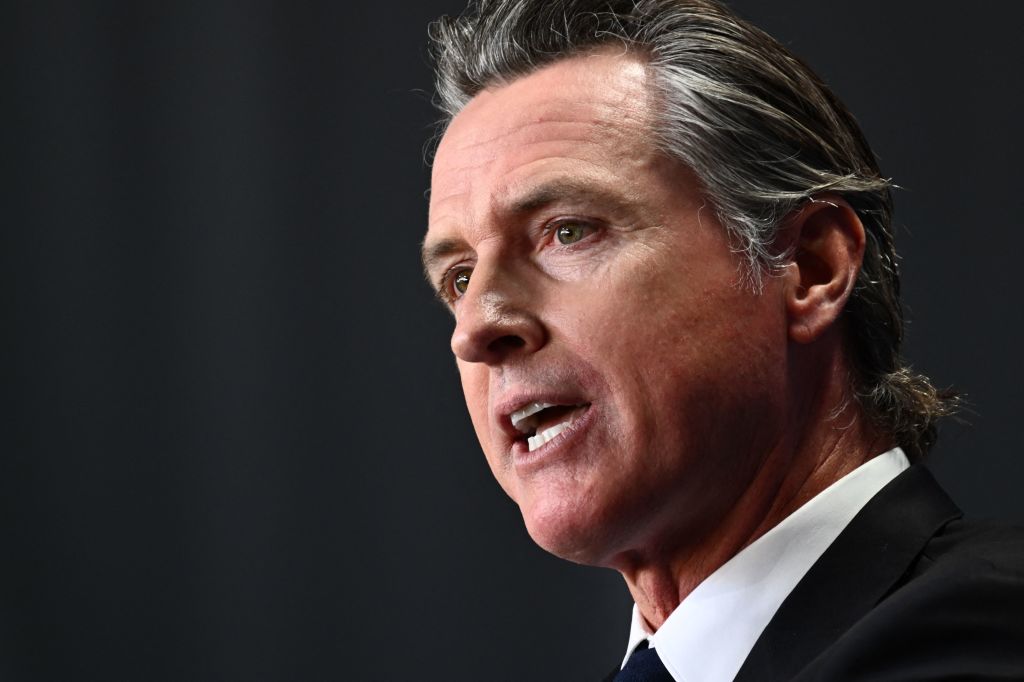

California governor Gavin Newsom insists a court injunction bars San Francisco from cleaning up its vagrants’ encampments, nests and shanties. He has announced the state will file a brief in the city’s behalf to get toxic federal rulings overturned. “I hope this goes to the Supreme Court,” Newsom said last week. “It’s unacceptable what’s happening on the streets and sidewalks.”

“We’re now complicit, all of us, at all levels of government and all branches of government,” Newsom added, blaming society at large, a brazen remark given his record. Newsom’s years as San Francisco mayor (2004-11) marked the city’s ascent as an epicenter of high-tech wealth, stagey identity claims and fantasy radicalism.

As mayor-elect in 2003, Newsom promised homelessness would be his number-one priority, just before he made his notorious end-run on gay marriage. Twenty years later, and many expensive initiatives come and gone, his housing-first homelessness policies are a self-evident flop. The failures involve public safety, hygiene, protection and esthetics.

Newsom is troubled — not from conviction, for Newsom has none to give. Along with San Francisco Mayor London Breed, he faces the brunt of public blame for California’s homeless crisis. Both are attempting to shift failures onto court decisions that have limited their ability to act and dodge responsibility for the zombie apocalypse, as both the Los Angeles Times and Sacramento Bee have pointed out.

Still, as calculated and self-serving as his ploy might be, Newsom is essentially asking the nation’s high court to right progressive wrongs, and in doing so, takes a sharp turn from Democratic Party omertà.

Many voters, Newsom understands, do not think vagrancy is a constitutional right, or that crapping in the street is an act of expressive individualism. Nor does his pal Marc Benioff, head of Salesforce, one of the municipal masters who is watching San Francisco’s elan and downtown retail wither before his eyes.

Destitution no longer bears the once heavy price of social disapproval and shame it did, but instead enjoys intricate legal rights. City officials, non-profit advocacies and service suppliers, low-end-developers and builders, prosecutors and judges, and the captive media insist on impossible solutions. Advocates traffic in miracle stories about turnarounds and acts of healing, while once orderly, attractive places turn into hellholes.

No one in the multi-billion-dollar homelessness complex can point squarely to hard drug use, thrill-seeking, improvidence, and vice to explain the decades-long surge of street people and penniless nomads.

One prominent homelessness expert, Dr. Margot Kushel, an internist at the University of California, San Francisco, confidently pitches nostrums that she calls “proven” cures. According to Kushel, “myths around homelessness” include the idea that “homelessness is caused by mental health and substance use problems.” Instead, she declares, “We know that most homelessness is driven by economic forces.”

“We’ve always known that most homelessness is a result, pure and simple, of poverty: the lack of a living wage, the lack of affordable housing and the insidious impact of racism,” Kushel adds. Kushel maintains the “vast majority of people who become homeless could be easily housed if there were housing that they could afford on their income.”

What income? The homeless are dead broke and scrounging. They are largely unemployable. Their plights have little or nothing to do with rising housing costs or income inequality. They often have lots to do with fentanyl, heroin, crack, methamphetamines, and that old-fashioned, get-out-of-your-head favorite, alcohol.

Reputable property owners do not want crazies or drug-addicts, ex-convicts or indigents for tenants, and they have good reasons for this. It’s not only the homeless who want aid. Many Californians living on the edge face what advocates call “housing insecurity.” They too would like taxpayers’ help with the rent through Section 8-style subsidies or perhaps direct payments.

Many state residents support detention and internment of the intractably addicted and insane, by force, if necessary. They want to jail petty criminals, aggressive panhandlers, and drug dealers. They want homeless encampments, if any, in restricted zones far away from metro centers. They don’t want to fund an infinite number of “tiny homes.” But the ruling elite and fellow citizens are emotionally incapable of stigmatizing or policing broad-based social pathologies that are at the root of the crisis.

If Newsom were more than a leftist windsock, he would have long ago condemned Martin v. Boise, scoffed at racial reparations, foresworn climate eschatology and identity politics, championed parental consent in school-based gender issues, and not have pledged a Senate seat to a black woman.

Newsom remains a political tease. He’s a master at keeping himself in the limelight and gossip news. His presidential aspirations underline an insatiable appetite for power and celebrity.

Newsom awaits a 2024 Democratic Party presidential draft, but he can bide his time until 2028. Newsom is fifty-five years old, and time is on his side. Unlike shuffling Joe, he is not going away soon, and his ambitions are as yet unquenched.