How will states perceive themselves and each other after the pandemic? This is not just a matter of narcissism; it is fundamental to international politics. Such ‘soft power’ is, as Joseph Nye argues, crucial to the clout of countries on the world stage; it allows them to convince rather than coerce in achieving their objectives. Whether it be the British model of democracy, French culture or good governance, these values complement a state’s hard power of armies, bombs and bullets. In today’s information age it is not ‘whose army wins, but whose story wins.’ States may claim that they dealt effectively with coronavirus domestically or internationally, but when this is all over there will be clear winners and losers. This post-coronavirus assessment will be an international propaganda competition redolent of the Cold War. The stakes are high and could lead to a realignment of the power rankings of states and even an acceleration of a post-American world.

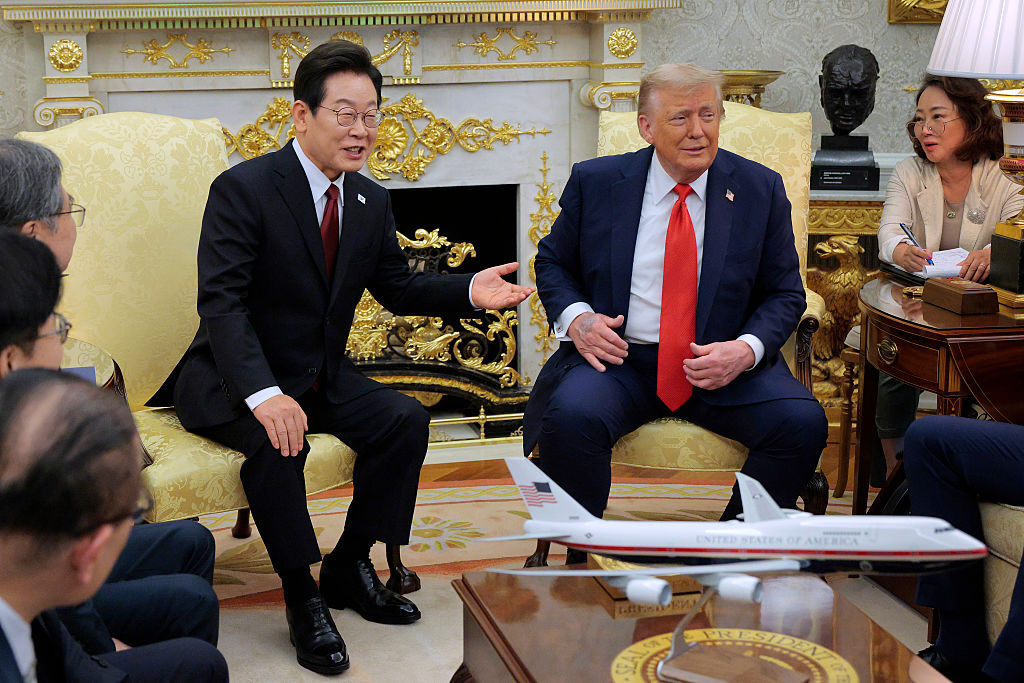

At the very beginning of the coronavirus outbreak, Donald Trump blamed China’s backward wet-markets for causing the outbreak. He pointed to an international league table compiled by the World Economic Forum to claim that the United States was the best prepared of any state to withstand an epidemic. That league table had the USA at the top, Britain second and only two non-western nations in the top 10: Thailand and South Korea. China was ranked 51st.

When this pandemic is over, US ability to manage a crisis will have taken a hit and with it its credibility. Britain’s and France’s will also have suffered. But above all, so will the longstanding international perception of the superiority of western health services and efficiency of democratic government. An element of the West’s soft power will have lost its potency.

But the assessments post hoc will not just be about health care systems. They will also be about states’ democratic robustness. This is an important soft power lever pulled by western states from the moral high ground to convince others ‘less democratic’ than themselves of the righteousness of a particular path individually, or collectively such as through the United Nations. After coronavirus, will western nations be able to wield that democratic moral weapon so convincingly? Britain and France, both so present for now on the international stage, might not like the answer to that question.

Will it be so convincing for the UK to preach in the future to regimes that adopt authoritarian measures when confronted by their own domestic crises now that the UK has demonstrated its lack of faith in the civic virtues of its people by its lockdown?

France, too, will find her international image as a liberal democratic state tarnished by president Macron’s imposition of one of the earliest and harshest lockdown regimes anywhere. How will French leaders remain credible in preaching to the likes of Viktor Orbán’s Hungary (as it has done) or taking the moral high ground in international organizations to denounce digital surveillance of citizens by ‘undemocratic’ states (as it has done), when France has carried out on its citizens in just over three weeks nearly ten million physical police checks and imposed over half a million fines?

Coronavirus has been a crash test for components of the West’s soft power arsenal. The result is not positive. Britain and France, up to 2019 regularly ranked first or second in the annual Soft Power 30 international tables, are now likely to sink. The effect will be felt slowly. Their foreign policies will be gradually constricted, most notably their tendency to engage in liberal interventionism around the globe. American isolationism may accelerate. Decline of the rules-based liberal international order — long promoted by the West — may be accelerated. Russia and China are already exploiting these weaknesses.

Some states will emerge favorably. Within Europe, the likes of Germany, Sweden and Holland should command greater credibility in terms of health care systems and practical democratic values, enhancing their soft power (presently ranked third, fourth, 10th). Will some harsh critics see a correlation between the severity of lockdowns and democratic robustness? How will the exemplary role of these ‘northern states’ play out in the already fraught politics of the EU with the ‘southern states’ (that now include France)? Other places such as South Korea, Taiwan and Hong Kong have given practical health system and governmental lessons to the West.

The European Union — solely reliant on soft power — has been diminished internationally by its internecine squabbling, lack of reactivity, poor coordination and overall international absence. Only this week, the head of the European Research Council resigned citing the EU’s bureaucratic sloth and lack of initiative in blocking the search for major research solutions to the epidemic. While Italy’s prime minister Giuseppe Conte has said the entire EU project now risks failing.

The United States of America, too, has left a deteriorated image of the wealthiest and most developed great power. This could soon hasten a post-American world, just as the beginning of the 20th century saw a post-British world or the 19th century a post-France world.

This is where things stand today, and we have not even begun to see how successfully states will surface from the pandemic. Success, or lack of it, will have even greater consequence for states’ future power, not in terms of soft power, but the hard power of a nation’s economy. That will be the real test that will condition the realignment of the world’s great powers. And the frightening thing is that history suggests that when great power realignment takes place, wars follow.

This article was originally published onThe Spectator’s UK website.