Should we fear a new martial spirit in Japan? Is there a samurai lurking inside those armies of gray-suited corporate men waiting to spring forth?

Even though Japan’s constitution, drawn up by the Americans after the war, forbids military combat abroad, the fear of a Japanese militarist revival has never quite gone away, especially in China where memories of Japanese wartime atrocities are kept alive and easily manipulated for political ends.

One of the candidates to become the new prime minister of Japan, the former foreign minister Fumio Kishida, has promised to strengthen national security against China. He even hinted at the importance of defending Taiwan. Hawkish members of his conservative Liberal Democratic party (which isn’t particularly liberal at all) have expressed their wish to revise Japan’s pacifist constitution for many years already.

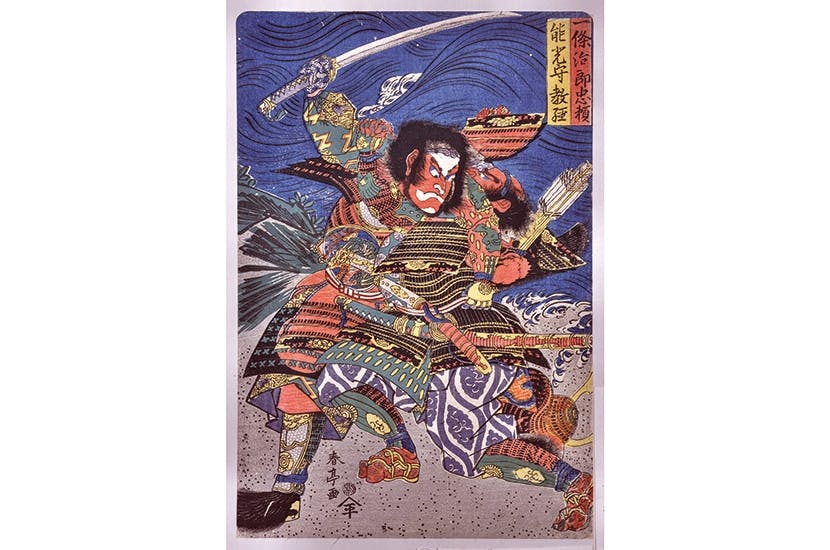

In fact, the Japanese martial tradition is a bit of a myth. Before the Meiji Restoration in 1867, only samurai, an exclusive social caste, were allowed to bear swords, and for a long time even they rarely used them. The warrior code of the samurai, laid down in Hagakure, a 17th-century text still revered by martial enthusiasts all over the world, was already a form of dandyism, a bit like knightly jousting in 16th-century Europe.

Japanese merchants cared more about money and sensual pleasures. The only martial spirit they knew was acted out in the kabuki theater. And peasants had nothing to do with warfare at all. Like the American cowboys, whose glamorous image was invented in Hollywood long after the Wild West was tamed, the glorification of the samurai spirit began mostly after the samurai themselves had become obsolete.

When Japan rebuilt itself as a modern nation in the late 19th century, one of the great instruments of modernization was the army. Sons of peasants and merchants could bear arms for the first time. Violence, or the trappings of violence, were no longer the privilege of a warrior caste. The militarism that was part of Japanese modernization was not so much rooted in ancient tradition as an imitation of European models, especially France (the army), Britain (the navy) and Prussia (the constitution).

After 1894, when Japan went to war with China, Japan was often belligerent. But again, this had less to do with a traditional martial spirit than with an attempt to protect Japan from colonial predators by mimicking them. Japan wanted to impress the West with an empire of its own — in Korea, Taiwan, Manchuria and other places — which would be as modern, indeed more modern, than any western possessions. The Japanese express train running through Manchuria already had air-conditioning in the 1930s. In the 1920s, Japanese government was relatively liberal. Young people read Marx, danced the Charleston and worshipped Charlie Chaplin rather than the emperor. But by 1937, enforced emperor worship and militarism had turned Japan into an authoritarian state, and the Imperial Japanese Army was running amok in China.

Even in 1937, however, many Japanese were not especially martial. Right-wing authoritarianism was in some ways a reaction to decades of westernization. The yearning for order and tradition, and resentment against liberal elites, big business and politicians, was especially strong in the provinces, as is true in many countries today. It shouldn’t be forgotten that people flocked to see James Stewart in Mr Smith Goes to Washington until the day before the attack on Pearl Harbor. After that, ‘frivolous entertainment’ and ‘foreign culture’ were forbidden (unless it was from allied Italy and Germany).

Crawling out of the ruins of bombed-out Japanese cities in 1945, most Japanese were heartily sick of anything to do with war. The pacifist constitution, even though it was written by the foreign victors, was widely popular. In an ironic twist, the myth of the samurai spirit received a boost from those same victors.

Since Japan had no equivalent of Hitler (certainly not Emperor Hirohito, who was many things, but not a dictator), or a Nazi party, something else had to account for Japanese bellicosity. The relatively uninformed Americans, backed by Japanese leftists, blamed ‘feudal’ Japanese culture, specifically the ‘warrior spirit’. Kabuki plays featuring samurai heroes were banned, as were movies about sword-fighters or anything else that was assumed to promote ‘feudalism’.

This cultural analysis is also why the Japanese were constrained by a pacifist constitution, whereas the Germans were not. Japan was not trusted with the use of military force. Like a reformed alcoholic, total abstinence was required. Again, most Japanese did not object to this. Not being bossed around by men in uniform was felt to be a liberation. Businessmen could concentrate on business without unwelcome military interference. The US would guarantee Japan’s security, while the Japanese increased their wealth.

But not everyone was happy with this arrangement. Leftists resisted the security treaty which allowed the US to continue their occupation on military bases all over Japan. And right-wing nationalists resented the pacifist constitution, which they saw as a foreign attempt to rob Japan of its national sovereignty. But since these nationalists were also fiercely anti-communist, they were prepared to put up with US dominance.

Nobusuke Kishi, grandfather of the former prime minister Shinzō Abe and the current defense minister Nobuo Kishi, was a perfect example of this. As the top bureaucrat in charge of slave labor in Manchuria, and a member of the cabinet that went to war with the US, he was arrested as a war criminal. But he was released at the beginning of the Cold War, played golf with President Eisenhower, and was the prime minister who rammed the US-Japan security treaty through parliament in 1960. His dream to revise the pacifist constitution was never realized — which is why Shinzō Abe was so keen to promote his grandfather’s cause, so far also without success.

The split over Japan’s constitutional pacifism has had serious consequences. One of them is the continuing conflict over Japanese history. So long as liberals defend pacifism by recalling Japan’s wartime atrocities as a warning, the revisionists will downplay or even deny Japan’s dismal wartime record. They argue that Japan is no different from other countries. War is a bloody business. But that is no reason why Japan, as a sovereign nation, should not have the right to use military force, they say. Those who claim that Japan’s wartime behavior was any worse than that of other nations are deluded by Chinese communist propaganda.

Conservative Japanese politicians often refuse to make official apologies for the war for that reason, and school textbooks are still published that omit such atrocities as the 1937 Nanking Massacre, or the practice of forcing women into prostitution for the Japanese army. This has nothing to do with a slumbering martial spirit in the Japanese people, or a cultural inability to face guilt, and everything to do with a deep conflict about the post-war constitutional order.

Japan’s incapacity to use its so-called Self-Defense Forces in combat abroad was felt to be particularly humiliating by Japanese conservatives when the US wanted allies to fight wars in the Middle East and elsewhere. This feeling would become even more acute if Taiwan were to be threatened, and the US might possibly intervene, not only on behalf of the Taiwanese, but also of Japan, whose interests would be directly involved.

The conservative revisionists are right to call for a proper debate in Japan over its constitutional arrangements. Squeezed between an erratic US and an aggressive China, total dependence on the US for Japan’s security is no longer so reassuring, especially after Donald Trump’s America First policy and the debacles in the Middle East. The question is how this necessary debate and constitutional revision would take place, which brings us back to the matter of Japan’s alleged martial spirit.

Ever since the end of the Allied occupation in the early 1950s, Japanese conservatives have grumbled about the softening of Japanese youth. To remedy this, right-wing politicians promote patriotic education, renewed worship of the imperial institution, remembrance of heroic war dead and so on.

These are precisely the wrong ways to go about it. Rightly or wrongly, to the Chinese and others who suffered from Japan’s last war, this smacks of nostalgia for the old militarism. It would be far better if a liberal Japanese government were to lead the discussion about national sovereignty, military responsibility and constitutional revision. But since the opposition is too feeble and disunited to break the Liberal Democratic party’s hold on power, this is unlikely to happen soon.

And so the status quo will continue. Most Japanese hope that war will never come to disturb their peace, and if it does, that the US will protect them. Some Japanese will still use the horrors of the past as a warning against change. Some will counter that with denials of historical truths and visits to a Shinto shrine to pray for the souls of indicted war criminals. And some people abroad will continue to fret about the Japanese warrior spirit, which remains a lot of nonsense.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.