The collapse in Mongolia’s exports of cashmere legwarmers to Russia serves as a bellwether of East-West superpower rivalry. For decades, Mongolia enjoyed a lucrative trade selling cashmere clothes to Russian customers, knitted underwear and leggings being the fastest-selling items. At the outset of the Ukraine invasion, cashmere sales went through the roof as mothers across Russia bought their sons underwear to keep them cozy in their tanks and trenches. Even as the war’s first winter set in, however, sales plummeted, as sanctions started to bite and fewer mamushkas could afford natural-fiber undies.

Mongolia’s cashmere exporters are now in a rush to redesign their products for a primarily western market, where legwarmers have not been in fashion since Jane Fonda’s 1980s workout videos. Even warmer than cashmere, I discovered while in this brutally cold country, is wool harvested from yaks, and apparently yak-wool clothes are about to storm the world’s knitwear industry. Yak is the new merino, say those in the fashion know, and Mongolia desperately hopes that other trade will follow in the yaks’ footsteps.

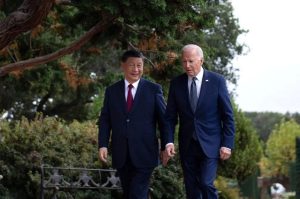

Mongolia is in a delicate situation. It’s dependent on both Russia and China but it also increasingly looks longingly towards the West. This year it has humbly extended invitations to visit to both Xi Jinping and to Vladimir Putin, while also trying to persuade Elon Musk to set up a factory on its home soil. This is what Mongolia calls its Third Neighbor Policy — a phrase coined by former Secretary of State James Baker during an Ulaanbaatar visit.

It is a strategy to strengthen relations with democracies in Asia and the West, which the Mongolians ultimately hope will stave off the threat of invasion from Beijing or Moscow, though nobody wishes to antagonize these authoritarian neighbors. “We believe in human rights, freedom of speech and democracy,” says Jargalsaikhan Dambadarjaa, a well-known journalist in the capital. “Whoever agrees with these values is our friend — but we’re not going to punch anybody who disagrees with them and nor do we want them to punch us.”

Mongolia depends entirely on Russia for its fuel supplies while almost all exports go to China

The desire not to be punched means Mongolia can’t embrace any third neighbors too enthusiastically. After Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, both the West and Moscow hoped for Ulaanbaatar’s support, but it was no wonder that Mongolia kept quiet and abstained from United Nation resolutions. Mongolia depends entirely on Russia for its fuel supplies, while almost all exports from this country of around three and a half million — a population equal to a single district of Beijing — go to China. “We can’t sanction Russia. That’s the reality,” says Byambasuren Guntevsuren at Mongolia’s Foreign Ministry. “We don’t want to be seen as black or white, but our problem is that the classic idea of neutrality is shifting.”

Mongolians are aware their country wouldn’t exist had it not been for Joseph Stalin, who at the Yalta conference insisted on its sovereignty from China as one of his conditions for Roosevelt’s wish for the Soviets to join the war against Japan. In 1963, Britain became the first western country to establish diplomatic relations with Ulaanbaatar, mainly because it saw it as a rare listening post in the communist bloc. “The windows of Russia are so few and generally so tightly sealed that we should make full use of any which give the smallest glimpse of the interior,” wrote a British intelligence officer.

When Russia was blocked from the Swift payments system, Mongolia ran out of oil until a compromise was found. Most trade was suspended, along with revenue from overflights. The economy was already suffering from China’s three-year closure to human traffic of its 2,900-mile border with Mongolia. Young Russians absconding Putin’s military draft became the largest group of tourists in Mongolia, but Ulaanbaatar is much more enthusiastic about attracting westerners. To Moscow’s rage, the country recently introduced English as the priority foreign language in schools, many of which are staffed by Russian-speaking teachers who still place portraits of Putin on the walls.

In Mongolia’s early post-communist years, since there were few jobs left in the state sector, an exodus from Ulaanbaatar to the rural steppe and taiga occurred. Here, beset by a series of dzuds, or winter droughts, in temperatures that can get colder than the North Pole, urban Mongolians realized they were no good at being nomadic livestock herders. This is when they discovered the immensity of their reserves of copper, gold, rare earth elements that comprise the sexiest bits of the Periodic Table, coal, plus sunshine and wind for renewable energy projects. Today, nearly half of Mongolians still survive as nomads, while the other half live in the capital. Their language may sound like a Beatles record played backwards, while their cuisine is fine if lumps of sheep fat and fermented mare’s milk appeal, but Mongolians are keen to become as wealthy as other fast-growing Asian economies.

“What we are really after is foreign investment,” says Byambasuren. “Next door is China, happy to invest in everything, but we want to be attractive to western investors and countries with whom we share common values.” But whereas China has bountiful cash to invest in Mongolia’s minerals based on its long-term strategy, western companies are motivated by profit and rarely have the support of their governments. Mongolia has until recently been regarded as beset by red tape and embezzlement. Huge protests erupted in December 2022 after a massive corruption scandal in coal sales to China came to light, and although Rio Tinto is digging deep beneath the Gobi Desert at its Oyu Tolgoi mine to extract vast amounts of copper, the company had difficulties in its negotiations with the government for many years.

In Ulaanbaatar, western investor reluctance is a cause for frustration. Since 2016, the government has passed a wide array of reforms to liberalize the economy and smash corruption. On top of progress at the Rio Tinto copper mine, the French nuclear fuels producer Orano reached agreement with Mongolia in October last year to extract large quantities of uranium for China’s reactors. China is the biggest market in the world, right next door.

While Mongolians argue the Third Neighbor Policy is all about attracting business and that trade is what matters, on a moral level they are increasingly uncomfortable about having to appease Russia. In Ukraine, the highest military casualties among Russia’s forces have been soldiers recruited from the republics of Tuva and Buryatia, whose peoples and languages are close to the Mongolians. “We see it, we don’t like it,” says Jargalsaikhan. “Those young brothers get killed and for what? We have sympathy but we can’t do anything about it.”

As a lonely democracy on the Asian steppe, Ulaanbaatar wants most of all to build closer cultural links with the West. Mongolians are obsessed with their own cultural history, with Genghis Khan as their greatest inspiration. Genghis, or Chinggis, gives his name to everything from vodka brands to a new satellite about to be launched into space. In several Chinggis exhibitions in the West, Mongolians aim to celebrate the civilizing influence of Pax Mongolica, which after the initial slaughters of the bloodthirsty Khans, established centuries of peace and East-West trade under the rule of Genghis’s successors.

The London Coliseum recently staged The Mongol Khan, a play with 100 actors, throat-singing and horsehead fiddles. Directed by Prime Minister Rishi Sunak’s half-brother Hero Baatar, its success was a matter of national pride, especially since it was banned in China. Precisely because he’s such a hero for Mongolians, Ghengis Khan is a sensitive subject for China, which has in the past tried to erase references to Mongol culture from exhibitions about the Great Khan. Hero said his play is a vital part of the Third Neighbor strategy and the consummation of sixty years of UK-Mongolian relations. That may be true, but as Mongolia is well aware, it’s important to stay on friendly terms with all your neighbors.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.