Twenty-five years ago, bipartisan American consensus about China was built on hope, spin and money. Despite the trauma of Tiananmen Square and caution about China’s true economic intentions, many believed in the potential of capitalist principles to move the Chinese Communist Party into a more open, less aggressive posture. Henry Kissinger wrote books about it; pundits and think-tank scholars gave speeches about it; Republicans and Democrats alike parroted the line well into the twenty-first century. Tom Friedman even dreamed ambitiously of what the United States could accomplish if only it were willing to be “China for a day.”

What followed? As Harold Macmillan put it, “Events, dear boy, events.” And now the United States finds itself in a very different place, constrained to be far more honest about what China represents. There is increased understanding on both sides of the aisle about how little global acceptance of “Made in China” has changed China, and how much it has changed the West.

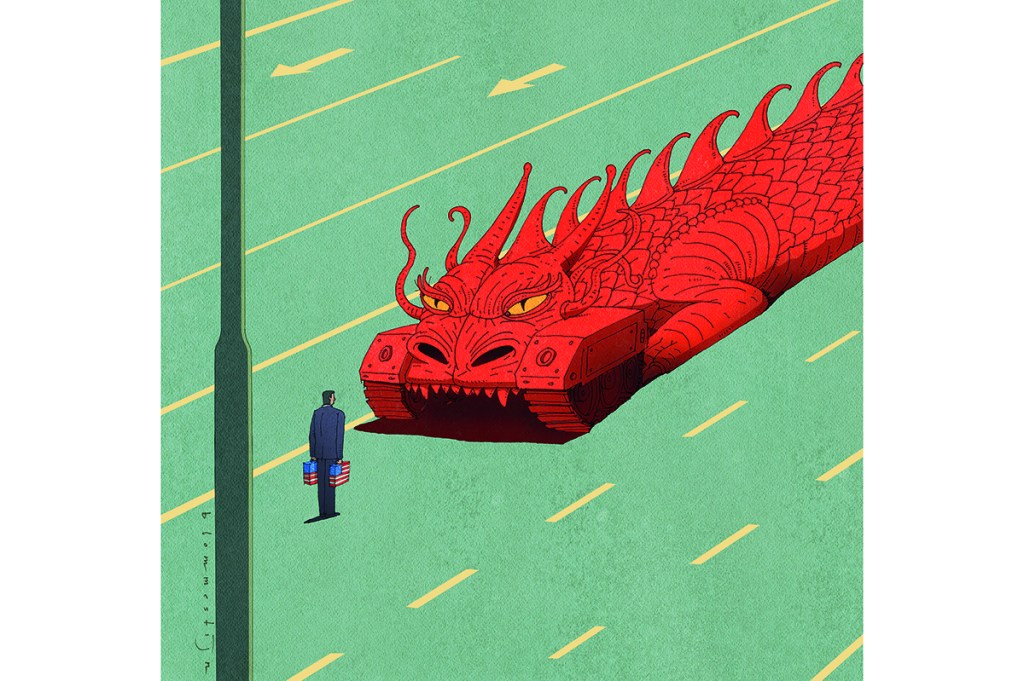

Enter the new China hawks, a generation of younger leaders who look at the country with jaundiced eyes. Without ties to the errors of the past and, in many cases, informed by careers in the military and industry, they have the lessons of China’s behavior in recent years at the front of their minds. And they intend to push back.

Chief among these new hawks is Representative Mike Gallagher of Wisconsin. In the just-installed Republican-controlled House of Representatives, Gallagher, aged thirty-eight, heads a new select committee on China. His mission is not for the fainthearted: reshoring supply chains, breaking economic dependency, targeting the CCP’s intrusion into the personal data of Americans, juggling concerns about the military and technology — and that’s all before getting to the question of Taiwan. But for those worried about China’s authoritarian turn — and eager to deter further Chinese aggression — his rise is welcome.

For Elbridge Colby, former deputy assistant secretary of defense and author of The Strategy of Denial — an influential work on the challenge of Chinese belligerence — the choice of Gallagher as committee chair is “a huge gain.”

“Gallagher is a geopolitical and defense strategist of the first order who has been thinking hard about this problem for years — well before it was in vogue,” Colby explains. “He fully understands the urgency of the situation and will bring a vitally needed seriousness, eloquence and practicality to the committee.”

It’s a big job for a young congressman.

In May 1997, in a nondescript room high in the Old Executive Office Building, President Bill Clinton took the stage before a gathering of business leaders to announce his push for renewal of China’s “most favored nation” trading status.

“The United States has a huge stake in the continued emergence of China in a way that is open economically and stable politically,” Clinton said. “Of course, we hope that it will come to respect human rights more and the rule of law more, and that China will work with us to secure an international order that is lawful and decent… We believe it’s the best way to integrate China further into the family of nations and to secure our interests and our ideals.”

The announcement was controversial. At the time, a left-right combination of Democratic labor groups and Christian Republicans in Congress raised concerns about China’s record on trade and human rights. But there were bipartisan endorsements too, including from House speaker Newt Gingrich, who said he’d support the move. After a contentious debate which saw labor-friendly House Democratic leader Dick Gephardt break with Clinton, the extension passed easily in a 259-173 vote.

The past is a different country. The consensus of the late 1990s is a world away from today’s Washington, where opposition to the PRC is a rare exception to partisan fracture. An anti-PRC orientation, now received wisdom among nearly everyone in America’s governing elite, is the cardinal long-term strategic achievement of Donald Trump’s presidency. And Joe Biden’s White House has, with minor exceptions, continued Trump policies toward China almost wholesale — tariffs and all.

If the question in 2017, at the start of the Trump administration, was whether opposition to China was the right position, the question in 2023 is how far that opposition should go. How we got here is a tale of China’s ratcheted insults and economic acceleration that reached a tipping point in the past four years.

First, there was the failure of the narrative advanced by Clinton in 1997: China was not, despite his hopes, integrated into the family of nations by trade relations, nor did it come to respect human rights. Instead, the Chinese regime prosecuted the genocide of Uighurs, the destruction of Hong Kong’s independ- ence and the de facto seizure of the South China Sea.

In a major strategic miscalculation, Xi Jinping’s regime deprived Western elites of the flexibility to maintain their “good relations” cover story by targeting them, their businesses and their political leaders. The repeated theft of intellectual property, expan- sionist mineral grabs across the globe and outright seizure of company assets undermined their status as a trustworthy trading partner.

Then there have been the embarrassing diplomatic errors, like the ill-conceived decision to humiliate President Barack Obama atHangzhou airport during the 2016 G20 meeting. Upon the arrival of Air Force One, there was no red carpet rolled out, or even stairs provided to exit the aircraft — forcing the president to use a rarely deployed exit from the belly of the plane. At the time, China expert Bill Bishop pronounced it “a straight-up snub… ‘Look, we can make the American president go out of the ass of the plane.’”

It was a calculation intended to humble and degrade the president of the United States — to which, predictably, Obama acquiesced — and the Chinese returned to this playbook in a meeting in Anchorage in early 2021, treating the Biden team even worse. Chinese diplomats shocked secretary of state Antony Blinken by deploying the language of Black Lives Matter and domestic activist groups in denouncing US “hypocrisy” on human rights.

“We believe that it is important for the United States to change its own image,” China’s top diplomat Yang Jiechi said, lecturing American representatives for fifteen minutes. “Many people within the United States actually have little confidence in the democracy of the United States.”

The Chinese regime took this aggressive approach just as its status around the world was growing more divisive. Its decision to pursue belligerent relations with all its neighbors in East Asia (with the telling exception of North Korea) was another mistake. In December 2022, Japan announced its plan to become the world’s third-largest defense spender after the United States and China. The move would have been unthinkable were it not for Xi’s overreach. China’s aggression in East Asia, incompetently pursued, has resulted in a wholesale reorientation of American global military power and the transformational reemergence of Japanese military power for the first time since World War Two.

Nearly all of America’s foreign policy elite — except for the handful sympathetic to the populist right — have been willing to make excuses for China so long as they kept making money and were not themselves targeted by the PRC apparatus. But Xi’s decisions galvanized an about-face. His choice to announce a “no limits” partnership with Vladimir Putin a week before the Ukraine invasion amounted to the formation of an anti-American, anti-NATO axis. And Xi’s decision to return Chinese governance to the Mao-era dictator-for-life system, affirmed in November’s Party Congress, has crushed the last remaining hopes for incremental liberalization.

And then, of course, there is the pandemic. The emerging majority opinion, notwithstanding pushback from the likes of Anthony Fauci, is that a leak from a Chinese lab is the likeliest cause of its spread, and that the response to this leak was made massively worse by Chinese officials’ lies, incompetence and censorship. If you believe millions of deaths and years of misery were caused by the CCP, then there should obviously be consequences.

Today, the pandemic drives the popular American understanding of China. Many American citizens outside the political and business elite already blame China for the hollowing-out of the American industrial base and note its land grabs in the American heartland, perceived with some justification as a byproduct of the grand project to bring the PRC into the family of nations.

In addition, the PRC has increasingly taken on the role of culture-war aggressor. The past few years brought one incident after another — LeBron James and the NBA, John Cena, Apple — where American companies and celebrities were forced to kowtow to their would-be overlords in the PRC. They even came for the Taiwan flag on the jacket in Top Gun: Maverick. The cumulative effect of this knee-bending is disgust — it has elicited bitterness and a desire for justice. Beginning to fulfill that desire, and providing a plan for the future, is now the job of Mike Gallagher.

Gallagher was born in 1984 in Green Bay, Wisconsin, the same district he now represents. His father, a Notre Dame graduate and an ob-gyn in a family of them, also owned Gallagher’s Pizza — “Italian food, Irish spirit” — the biggest impact of which was giving a young Gallagher the chance to deliver pizzas to Packers players, including quarterback Brett Favre. (“He asked for French dressing,” Gallagher recalls, “and when I ran to get him some, he said ‘You’re all right, kid.’ It was like God Himself told me I was all right.”)

Gallagher didn’t follow in either the baby delivery or the pizza delivery business. After his parents divorced and his mother moved to California, he spent much of the year on the coast going to Catholic school and trying to surf without much success; for summers and holidays he was in Wisconsin, never fitting in entirely in either place. He was ambitious in student government, becoming class and student body president, and showing an early affinity for foreign languages paired with an interest in global affairs.

“I always had an itch to kind of go somewhere different that no one in my family had gone to and that was different from Wisconsin or California,” Gallagher says. “I loved history and foreign policy, and I was always interested in the world outside of America.”

Gallagher was in his senior year in high school on 9/11. He recalls the attacks, as they were for so many in his age group, as “a massive shock to the system.” The Iraq invasion came in his sophomore year at Princeton; while working for the Rand Corporation that summer, studying Basque separatists in Spain, he became fascinated with the workings and operations of terrorist groups. When he went back to college, he changed his major and started studying Arabic.

“It’s a dumb decision, because then you have to have class every morning early. But I just loved it,” Gallagher says. “And from that moment on, I just became obsessed with the Middle East. I started to think, ‘OK, what, what would I do with these skills?’ I never had any interest in going to Wall Street, which is what everybody at Princeton did — certainly my friends who did that made a lot of money. But I just never had that bug.”

Torn on what to do, Gallagher turned to the Marine Corps — “the best propaganda organization in human history.” At a dinner for college seniors, sitting at a table with former counterterrorism czar Richard Clarke, Gallagher broached the possibility of joining the Corps. “The response from everybody at the table was, ‘well, maybe you should think about joining the CIA, or do something a little bit better with your Princeton degree than joining the Marine Corps,’” Gallagher recalls. “And I remember being so offended by that: ‘What are you talking about?’” The young fellow from Green Bay wanted to get out into the world. He cites Moby-Dick as inspiration: “As for me, I am tormented with an everlasting itch for things remote. I love to sail forbidden seas, and land on barbarous coasts.”

His first tour in Iraq came in 2006, working under CENTCOM during General David Petraeus’s tenure as a counterintelligence officer, interrogating potential terrorists and criminals during the onset of the US surge to win the war. Gallagher describes the experience as challenging, confounding his expectations, and he volunteered to return for a second tour soon after returning home. “In terms of a tactical and operational victory, I saw the surge work firsthand — going from chaos to order,” Gallagher says, but he notes that it “couldn’t turn the clock back on disastrous decisions like de-Ba’athification.”

After his second tour, Gallagher went to Washington, getting advanced degrees and his PhD from Georgetown before joining the Republican staff of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee and running successfully for Congress in 2016. The lessons from Iraq still stick with him — one of the reasons he’s become an outspoken critic of the “woke military” developments that put political correctness and gender-identity politics ahead of readiness.

“In the Marine Corps, when you’re at the tip of the spear, things are a lot messier than they seem when you’re sitting in an air-conditioned office in Washington, DC, making decisions about how you’re going to shape the world,” Gallagher says. “So I think a healthy respect for friction and unintended consequences needs to be the constant companion of a national-security professional.”

Any conversation with Gallagher can turn quickly from talk of football and his penchant for science fiction and fantasy novels — he is a fan of Joe Abercrombie’s “grim-dark” brand of genre fiction, “a more realistic view of human nature, complexity and sin” — into a discussion of the history of war and foreign policy, the Kellogg-Briand pact and the shift from NSC 20/4 to NSC 68.

He outright rejects the neoconservative label, though he has some fans in their corner of foreign policy — former George W. Bush speechwriter Marc Thiessen calls him a rising star, and he has a supporter in Mitt Romney-friendly radio host Hugh Hewitt.

“As someone who thought the war in Iraq in particular was a mistake, despite having fought in it myself, I consider prudence to be part of any sound geopolitical framework,” Gallagher says. “I don’t think that if you support arming Ukrainians, you’re a neocon. To me it’s a far different thing than supporting invading a country or two in the Middle East in the naive hope that you’re going to transform it into a democracy. So I worry that the term ‘neocon’ is being misused… The irony is that skepticism of democracy promotion was a key part of one of the original formulations of neoconservatism under Jeane Kirkpatrick. It’s been totally distorted.”

Gallagher calls himself an academic “neoclassical realist,” but regardless of the academic side of things, he puts real-world stakes in stark terms. He refers to Taiwan as an example where Las Vegas rules do not apply: what happens there does not stay there, but breaks the entire US defense approach to the “first island chain” that runs from the Japanese archipelago through the Philippines and Indonesia.

“My simpler view of the world is that we’re in the early stages of a new Cold War with Communist China,” Gallagher says.“The stakes are existential, and we need to win it. It’s a military and economic and an ideological competition, but part of winning it means you have to be very judicious about your foreign policy investments. And you have to understand the primacy of hard power.”

It’s in this area that Gallagher has been most critical of the Biden approach to foreign policy, confronting representatives of the administration on their love for “integrated deterrence,” which he blames for the failure to prevent war in Ukraine. “We need to understand why deterrence failed in Ukraine and learn that lesson so that it can be applied to ensure that deterrence does not fail in Taiwan,” Gallagher says. “The Biden Pentagon goes around bragging about the success of ‘integrated deterrence,’ which is bullshit jargon designed to justify cuts to conventional power under the naive assumption you can make up for those cuts with unproven technology, allies and soft power. Tens of thousands dead, millions displaced, trillions of dollars of economic costs and the risk of nuclear war is at a higher level than at any point since the Cuban Missile Crisis? I would not call that a success.”

If it’s done right, Gallagher believes the costs of deterring China from invading Taiwan could be much less expensive than many contend. “I think you could actually push their invasion plans out at least five years, if not seven years, for the cost of $10 billion or less. The Pentagon is spending that money on all sorts of things unrelated to the warfighter. Look at all the things we’re spending money on — for a fraction of that cost, we can prevent World War Three.”

Some prominent members of the new generation of China hawks agree that the real question is how far this new anti-PRC consensus will go, and how long it is likely to last. While bipartisan consensus on the dangers of the CCP-compromised app TikTok is valuable, it’s relatively low-hanging fruit — multiple governors have banned the app from government phones, and Missouri senator Josh Hawley’s measure to ban it from federal government phones passed easily in December. Gallagher’s select committee must help answer the more difficult questions.

“There is a lot of consensus on the challenge that China poses, and even that it is the primary threat Americans face — but that consensus is relatively superficial,” says Elbridge Colby. “What to do and how to do it is not yet agreed. And that is a major problem because we have no time to waste. We need to make significant moves at scale now.”

Colby and others hope to see more significant screening of investments (a position backed by Matthew Pottinger, former deputy national security advisor to President Trump), improvement of manufacturing and onshoring production capacity to be prepared for a major war (backed by Democratic representative Ro Khanna of California), and military investments to prepare a denial defense of Taiwan. On this last point, Gallagher and his fellow China hawks are vociferous: they believe China will try to seize the democracy of 24 million in the near future, and that a more focused approach to deterrence is the best way to prevent it.

“The paradox with deterrence is that in order to avoid a war, you must convince the other side that you’re actually willing to go to war, and that you have the capability to prevent them from achieving their objective,” Gallagher says.

Gallagher’s rise to this role may represent the first real test for the millennial generation of American political leaders. With so many lives personally touched by the failures of utopian approaches to the Middle East, and without the blinkers of the hopes and illusions that rise from a belief in the end of history, it’s an opportunity to chart a path that leaves the political labels and restrictions of the past behind.

When it comes to China policy, it’s important to understand that the developments bringing us to this moment were not foreordained — they were almost entirely a product of Chinese choices. It seemed for a time that our business and political leaders, even average consumers, were totally willing to let the PRC continue as things stood, even at the cost of damage to the American economy and way of life. But Xi Jinping and his Fifth Generation of leadership in the CCP decided to bring the West to heel.

“Your average American sees the hypocrisy that China induces in American industry, the obsequiousness and greed of Hollywood and the NBA. And there’s this sense that they’ve betrayed our trust. We bought China’s line about their peaceful rise hook, line and sinker. They used our gullibility to take advantage of our society. They became aggressive militarily in the South China Sea, they escalated threats against Taiwan, they broke their promise on Hong Kong,” Mike Gallagher observes. “But there’s also this sense of turning us into a nation of addicts. We’re addicted to the TikTok algorithms. We’re addicted to fentanyl, whose precursor chemicals come largely from China. We’re addicted to cheap Chinese goods and cheap Chinese debt. And Americans don’t like that.”

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s February 2023 World edition.