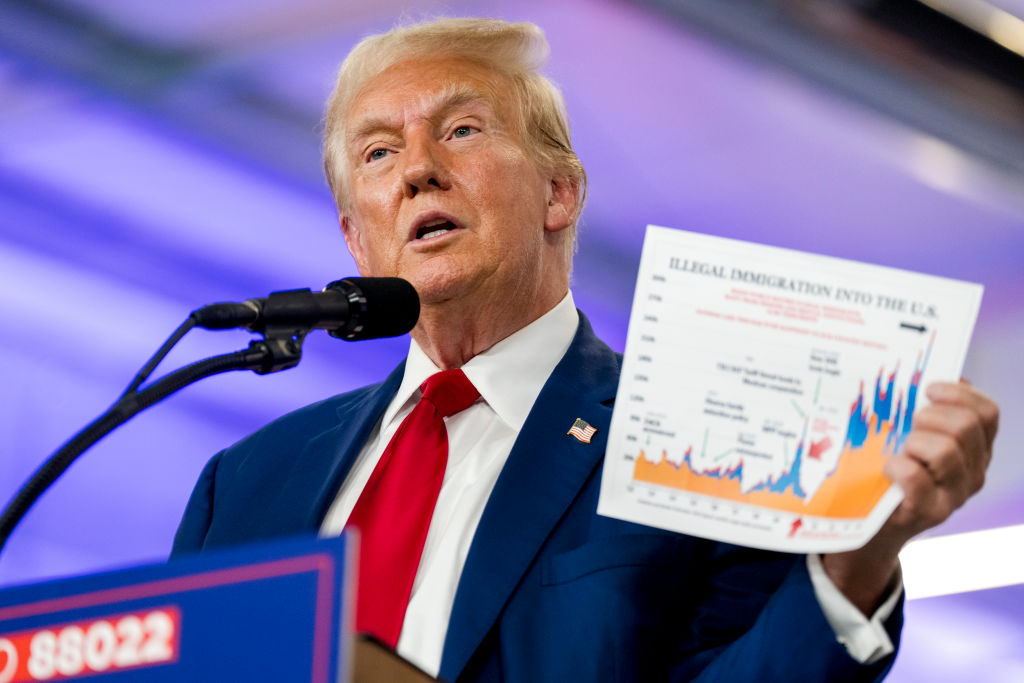

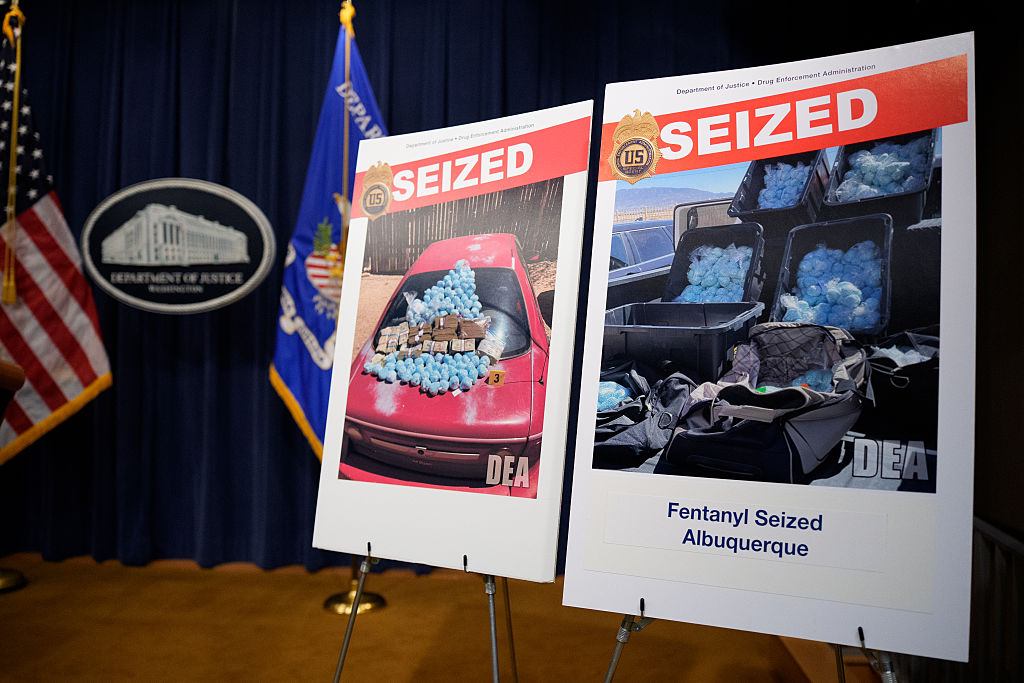

Over the past week, a security policy conversation that’s been taking place behind the scenes has emerged into the open. It involves those engaged on issues related to Mexico, trafficking across the southern border, and the cartel-fueled and China-backed flow of deadly fentanyl into the United States. It’s that the time has come to escalate where the Mexican government of President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador (AMLO) will not, including through the use of military force.

This consideration includes many factors: the fierce reaction to the kidnappings and deaths of Americans medical tourists crossing from Brownsville, Texas, into Matamoros; increased awareness of the corruption of the AMLO regime as it takes steps the American press rightly frames as anti-democratic; and a growing understanding that the dominance of the cartels over what a former ambassador estimates is 35 to 40 percent of the country is a deliberate policy choice by the Mexican government.

A Wall Street Journal column from former attorney general Bill Barr laid out the case over the weekend:

Under international law, a government has a duty to ensure that lawless groups don’t use its territory to carry out predations against its neighbors. If a government is unwilling or unable to do so, then the country being harmed has the right to take direct action to eliminate the threat, with or without the host country’s approval.

Even if AMLO were willing to move against the cartels, Mexico can’t do the job itself. Its criminal-justice system is dysfunctional: 95% of all violent crimes go unpunished. Pervasive corruption at every level of Mexico’s government makes it almost impossible to mount effective law-enforcement or military operations without the cartels being tipped off in advance. The big cartels have become potent paramilitary forces, with heavily armed mobile units able to stand their ground against the Mexican military.

The legislative trigger in this case is a proposal introduced by Republicans Dan Crenshaw of Texas and Michael Waltz of Florida which would grant the president Authorization of Use of Military Force against the cartels. As Democratic Representative Henry Cuellar, who hails from a border district, said in a press conference on Tuesday: “I say this with all due respect. We can help Mexico as far as they want us to help them. So there’s a lot more than we can do. But it’s up to the Mexican government to allow us to help them as much as we can.”

In his own news conference this week, AMLO dismissed such proposals as “pure propaganda,” and with more of his soft religious rhetoric about “not confronting evil with evil, but confronting evil with good” — good in this case meaning allowing the cartels to run rampant and murder at will, which has been the primary result of his “hugs not bullets” policy.

It’s not enough, as Barr notes in his op-ed, to just declare the cartels to be foreign terrorist organizations or pass an AUMF. A critical aspect of any real response will be to target the same Mexican elites who choose the silver side of the narcoterrorists’ offer of “plata o plomo.” As I wrote in 2019, “In much the same way the United States has targeted individuals connected to regimes like Iran, we ought to target the Mexican elites who do business with the cartels. They depend on access to our institutions for banking, health care and the education of their family members. They hold significant assets in the United States. All this can be taken away.”

One of the most infuriating aspects of US foreign policy over the past twenty years has been its increased focus on far-flung projects in nations of little strategic importance to the American people. Washington can seem to care more about the borders of other nations than its own — that line has become a trope but there’s some truth to it. The cartels’ dealers of death operate with impunity and have greater control of their side of the border than the US does of ours. They will continue to use this control to murder Americans with illegal drugs for profit.

The use of military force should never be undertaken lightly, and violent US actions against the cartels could destabilize the situation further. But then our relationship with Mexico has already become unstable, and it’s past time we took real steps to end the charade that much of Mexico is anything but a failed narco-state. This threat is close to home, and it can’t be ignored any longer. Without the application of serious force and real financial pain on Mexico’s corrupt elites, it will only get worse.