Japan will from Monday have yet another new prime minister: Fumio Kishida. He will be the country’s third leader in as many years, and news of his appointment has been met with neither enthusiasm nor much concern — mainly because nobody really knows who he is, or what to expect from him.

Kishida, the 64-year old former foreign secretary, was the most experienced of the four shortlisted candidates. He has been a minister in various posts for the last fifteen years without anyone particularly noticing his existence.

Kishida is a mild-mannered, self-effacing, former banker. He is a hereditary politician with three generations of his family having served in high office, and has clearly had his eyes on the top job for a while. He might have got there sooner but lost out in his bid to replace Shinzō Abe in 2020. He blotted his copybook during the early days of the pandemic when his suggestion of a 300,000 yen ($2,700) stimulus payment to all households in Japan was considered wildly extravagant and saw important backers edge away.

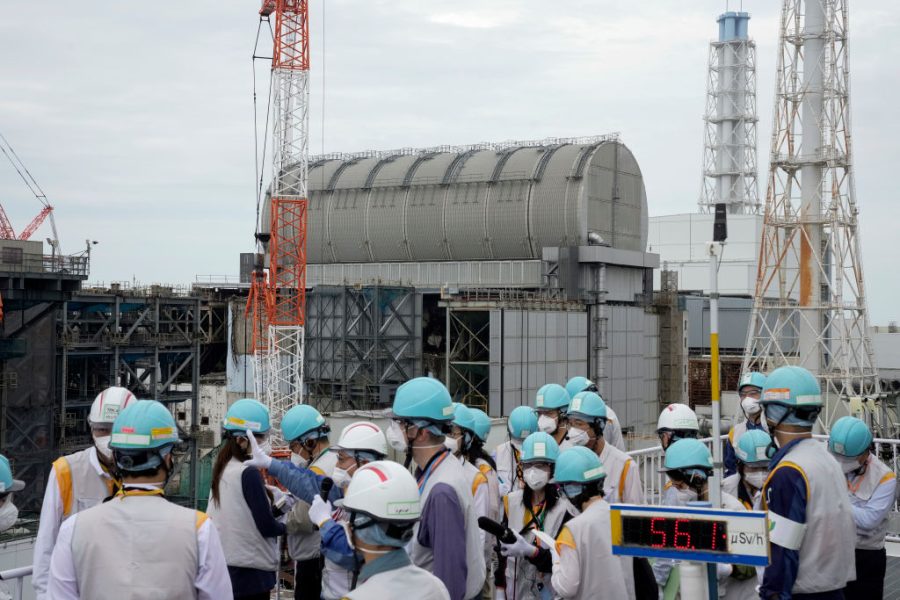

So what does he stand for? Kishida supposedly has left-wing tendencies, but by Japanese standard that still puts him to the right of most mainstream politicians in Western Europe. He is not keen on revising Japan’s pacifist constitution — and will likely pursue a softly, softly approach on foreign affairs. He is a strong supporter of nuclear energy — and might be less green-tinged than many world leaders. Unusually, Kishida speaks fluent English, having gone to elementary school in New York, when his father worked there.

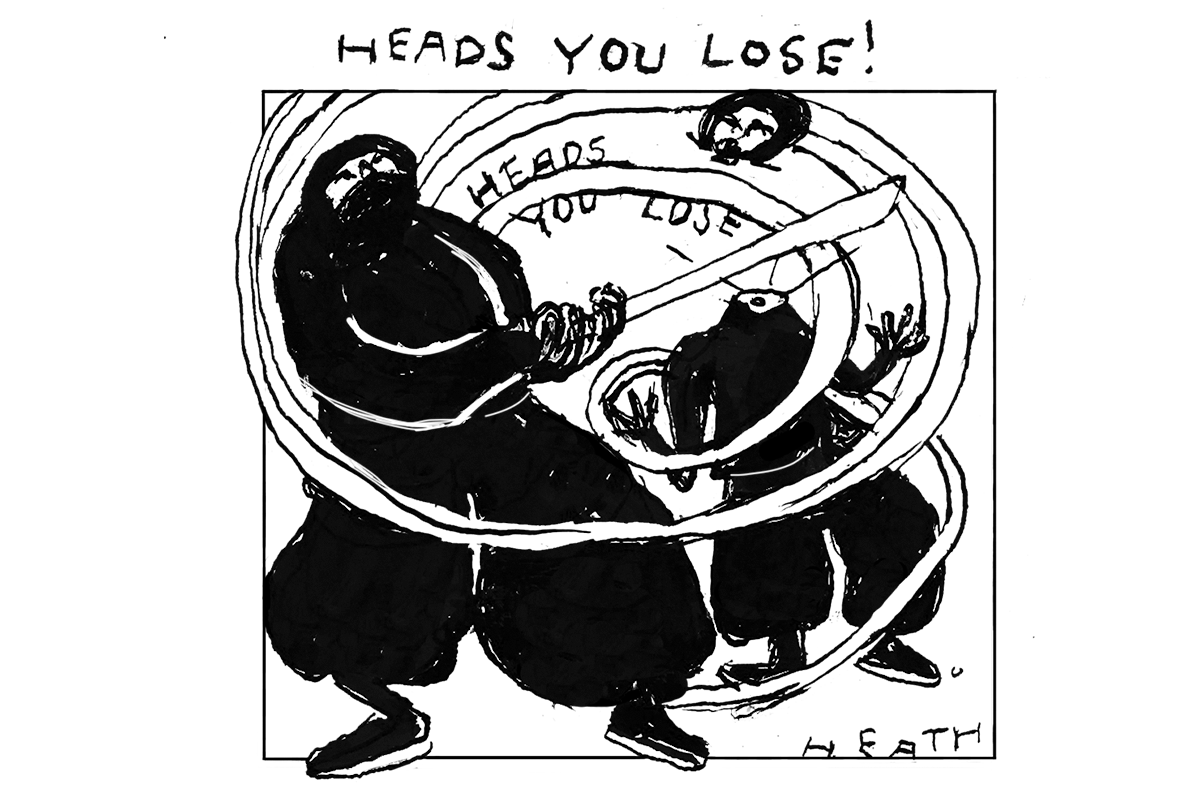

If Kishida is going to change anything radically though, it will be his own party. His mortal enemy, and the man without whom he might have had the top job earlier, is the aged kingmaker Toshihiro Nikai, 83, an archetypical ‘shadow shogun’ figure (a stock character in Japanese politics). Kishida has vowed to change the faction ridden Liberal Democratic party, where deals are done behind closed doors by men in black suits, and make decision making more transparent and officials accountable to the people. He will have his work cut out.

Kishida won through in a refreshingly brief and civilized leadership contest that highly unusually featured a 50/50 gender balance, with two women making it into the last four; a possible sign of changing times in Japan. The ultra-conservative Sanae Takaichi, who has been called a ‘Thatcher wannabe’, and who has held a series of minor ministerial posts, briefly threatened to cause an upset when she won the late endorsement of the ubiquitous Abe. But the one-time pink-haired punk rocker’s campaign fizzled out in the end.

Seiko Noda, the consumer affairs minister wasn’t seen as a serious contender, but the mainstream conservative has put down a marker with a creditable campaign. She seems like a sensible, down-to-earth sort, and she may yet have her day, but she unfortunately suffered the misfortune of public notoriety when it was alleged that her second husband was an ex-member of the Yakuza.

Despite claims that sexism played a part in Kishida’s victory, that’s not the way it feels out here. Canvasing my Japanese female friends, I’ve yet to meet any who opted for Takaichi or Noda. Indeed, the wife of a prominent academic told me she would ‘leave the country if Takaichi won’. The gender angle didn’t even feature much in press reporting of the contest, with even the ultra-woke Japan Times barely mentioning it, probably fearing that focusing on the issue could add credibility to Takaichi’s campaign and boost her chances.

Kishida was the best qualified of the candidates; if he is a bit dull, who cares? Not the Japanese certainly. One of the good things about Japan is the healthy contempt all politicians are held in, which is well understood by those in power, who rarely make attempts to ingratiate themselves with the public. They know it won’t work. Japanese politicians don’t talk much about their private lives or tearfully tell their story on TV programs. The underrated Suga had humble origins, which was highly unusual for a PM, but, unlike so many Western politicians, he never traded on them. And his wife didn’t appear once in public during his entire tenure in office.

We have seen Kishida’s wife, though. In the only controversy he has experienced in his career to date, he posted a photo of his wife serving him his dinner wearing an apron. This aroused criticism, mainly from outside Japan, for being anachronistic. But it was a storm in a green teacup, lasted about a day and did him no harm whatsoever. The Japanese really couldn’t care less about such nonsense.

Kishida starts with a clean slate then, and though he won’t get anyone terribly excited, he is seen as competent and dedicated. And with the Olympics and — God willing — the worst of COVID behind us, he has a fighting chance.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.