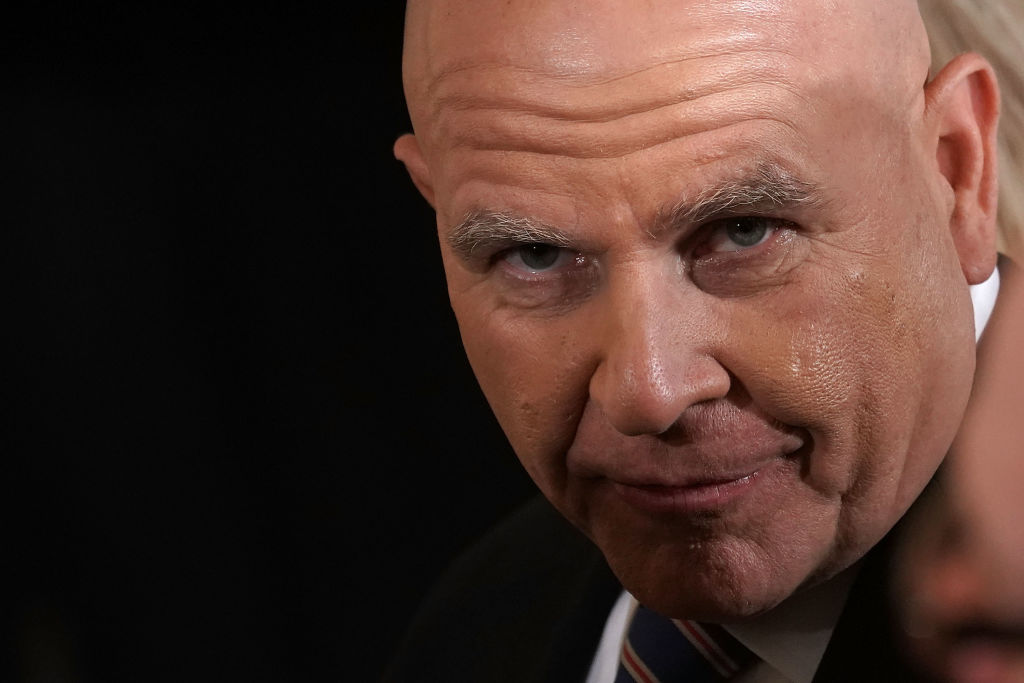

Former national security adviser Lieutenant-General H.R. McMaster says that the American public is misinformed by a false ‘defeatist narrative’ that has undermined the United States’ long war in Afghanistan.

McMaster made this curious remark at an event held by the Foundation for Defense of Democracies, where he is chairman of the Center on Military and Political Power. Even more peculiar was McMaster’s suggestion that only certain kinds of people are in any position to render a verdict on America’s military interventions:

‘A young student stood up and said, “All I’ve known my whole life is war.” Now, he’s never been to war, but he’s been subjected, I think, to this narrative of war-weariness.’

McMaster implies that those who have not been to war know nothing of what they speak. Therefore, they are ill-equipped to judge whether America’s wars have been worth the cost in blood and treasure. Not only is this sentiment wrong, it is also dangerous, and the sort of talk which widens the civil-military divide.

McMaster’s three decades of service in uniform afford him a unique perspective on matters of war and peace. But this perspective is not necessarily the one the nation should adopt, especially if his views come close to manifesting the symptoms that Isabel V. Hull calls ‘institutional extremism’.

In Absolute Destruction: Military Culture and the Practices of War in Imperial Germany (2004), Hull defined institutional extremism as ‘the repeated and unlimited application of the military’s expertise, that is, the use of violence’, regardless of political context. When the means overwhelms the end, violence is ‘pursued because the institution keeps on generating violence according to quasi-automatic mechanisms’.

‘Results matter,’ retired Army colonel Douglas Macgregor told me recently. Do the ends of the interminable War on Terror still justify its means, the violence that the US has wrought upon the Middle East, and upon itself?

In the case of Afghanistan, the lack of progress cannot be attributed to a lack of effort. Since 2001, US forces have suffered 2,419 fatalities, but the Taliban alone has suffered nearly 25 times as many dead. Though number of American troops in Afghanistan peaked in 2011 at close to 100,000, in 2018 the US released 7,362 pieces of air ordnance in Afghanistan, the most since, perhaps, the early days of Operation Enduring Freedom in late 2001.

While a strong argument can be made that the war effort was handicapped by unreasonably restrictive Rules of Engagement, the quantities of neither troops nor firepower have managed to move the needle in any significant fashion. Yet the war persists with the strategic and political situation unchanging. At what point can we expect the bloodletting to yield tangible results?

McMaster’s thinking logically arrives at one of two destinations. Either the US wages war in perpetuity for the sake of it, or it wages war in the never-ending pursuit of total victory, and with no regard for cost in either scenario. If McMaster and others in favor of continuing the Afghan war genuinely understand war as an instrument of policy, then they must assess the war’s costs versus its strategic gains. Instead, they have convinced themselves that the enemy is forcing their hand, and the fight must go on until the Taliban and every other enemy lay down their arms and surrender unconditionally.

This is the very definition of institutional extremism. Instead of looking for ways to achieve a reasonable if unsatisfactory outcome, or at least to better leverage military force, McMaster and other war-supporters are looking for reasons to sustain the fight.

An Afghanistan veteran tells me that we have two options in Afghanistan: total withdrawal, or relentless confrontation. There are alternatives, of course, such as the ‘Terminator Doctrine’ suggested by The National Interest’s Gil Barndollar, himself an Afghan war veteran. An I’ll be back policy involves withdrawal from an inherently unstable country, with the caveat that overwhelming force will be used in the event of further threats emanating from Afghanistan.

Barndollar’s idea has a certain logical, if not strategic, sense, but the Afghanistan veteran with whom I spoke characterized it as a surrender that would render meaningless the untold sacrifices of the past two decades. Such sentiments are common among those who have risked everything for this country. They did what they were asked to do, and the last thing they want to hear is that there is no pay-off in the end.

Soldiers are human, however, and their word should not be taken as gospel, even on war. While the counsel of those who have been to war is critical to decision-making, it is often the fact that their proximity to bloodletting means that their counsel ought to be considered with caution.

Violence, Isabel Hull explains, ‘is the province of emotion’. The ‘terror of being killed and the anxiety of killing (the breaking of a fundamental taboo) release powerful emotions’. The military intends to ‘channel violence in a systematic fashion toward specific ends’. In other words, it is supposed to ‘calculate and operate coolly under circumstances of white-hot passion’.

McMaster and the men and women who have fought in our wars are at least partly influenced by their experiences. As abortion and gun control summon powerful emotions, so debates on war strategy evoke the horrifying, kill-or-be-killed nature of conflict. Veterans are also influenced by the memory of friends who have lost life or limb.

It is entirely understandable the those who have fought and bled in war would want their sacrifices to be valued and to lead to tangible outcomes. But war is ultimately a policy venture, and its outcomes are not always commensurate to the sacrifices made in the fighting. Decisions relating to war and peace must reflect policy objectives, at a cost the public is willing to endure. Otherwise, wars do not serve the national interest.

The American public wants out of Afghanistan. So do a large percentage of veterans and their families. McMaster may be right when he says that the public does not understand what is at stake in Afghanistan But, like their president, the American people have the ‘right to be wrong’. It is critical to civilian control of the military, and to civilian democracy, that veterans uphold that principle, and encourage all Americans to engage in the debate, instead of advancing personal policy agendas by exploiting the differences between those who have served and those who have not.