The ice on my right breast is a painful reminder of the limbo I currently find myself in: the anxiety-provoking space between a biopsy and the results. The time when you try to think positively — as if your magical thinking could change the results, the nature of whatever cells the needle procured. I’m simultaneously telling myself ‘worry is praying to the wrong God’ and repeating the word ‘benign’ over and over and over again. But the knot in my stomach is wondering if I’m about to enter a nightmare.

You do your best to stay present but work falls through the cracks. You explain it away by apologizing and vaguely mentioning that you have some ‘health stuff’ you’re dealing with: nothing serious, just annoying.

It was almost exactly a year ago when Kate texted me and asked me to cover a shift for her. ‘Just some health stuff,’ she wrote. She’d found out she had a rare ovarian cancer. It was Stage 1; since she was only 30 the doctors thought the prognosis was good. But after the first surgery and the first round of chemo, the cancer had spread. It was aggressive.

I was there the day after they found out the first treatments weren’t working, bringing homemade soup and cornbread. Her sister came down to get it. I asked her how she was doing; she looked exhausted. I’ve never known two sisters to be as close as Kate and Sarah. ‘She’s my soulmate,’ she said. ‘We have just been crying and holding each other.’ But even then, it never occurred to me that Kate would die. She was so light. Her smile was infectious. Everyone loved her.

Everyone. She was always thinking of others. But shortly after dropping off her soup, I stopped hearing from Kate. And shortly after that, her sister started a GoFundMe for her escalating medical bills. It was only a matter of time before her sister put out a desperate plea on the GoFundMe for anyone who might know of any doctors who could work miracles. The hospital had taken out a large portion of her stomach and intestines. But the cancer continued to spread and they sent her home.

My aunt, who had recently lost two friends to ovarian cancer, told me the surgery Kate received was ‘last hope’ surgery and to prepare myself for her death. During this whole time I was just sending her texts. Hearts, rainbows. Messages telling her I loved her. Even though it must have been nice to know how loved she was, she probably had very little interest in hearing from the living as she stared directly into the face of her death.

She died in January 2021, on the tail end of a plague. We held a Zoom memorial. As Zoom memorials go, it was beautiful and moving. Her sister was there, as well as her mother and father. Her father had the 10,000-mile stare and I looked at a family that would never be the same.

That pesky ‘health stuff’ took Kate’s life in six months. Six. Months. And I can’t help but think about Kate as I ice my breast, swollen from the two needles. The reassuring messages from the few people I know, telling me not to worry, it’s all going to be OK. ‘That’s what Kate thought too,’ I say. ‘And she’s dead.’ In my attempt to find any peace at all in this limbo, I pray, I meditate, and I’ll entertain any kind of woo that might serve to distract me or offer me insight. I do a Sacred Path Card reading, a Native American version of tarot cards by Jamie Sams — and of course I pull the ‘Shaman’s Death’.

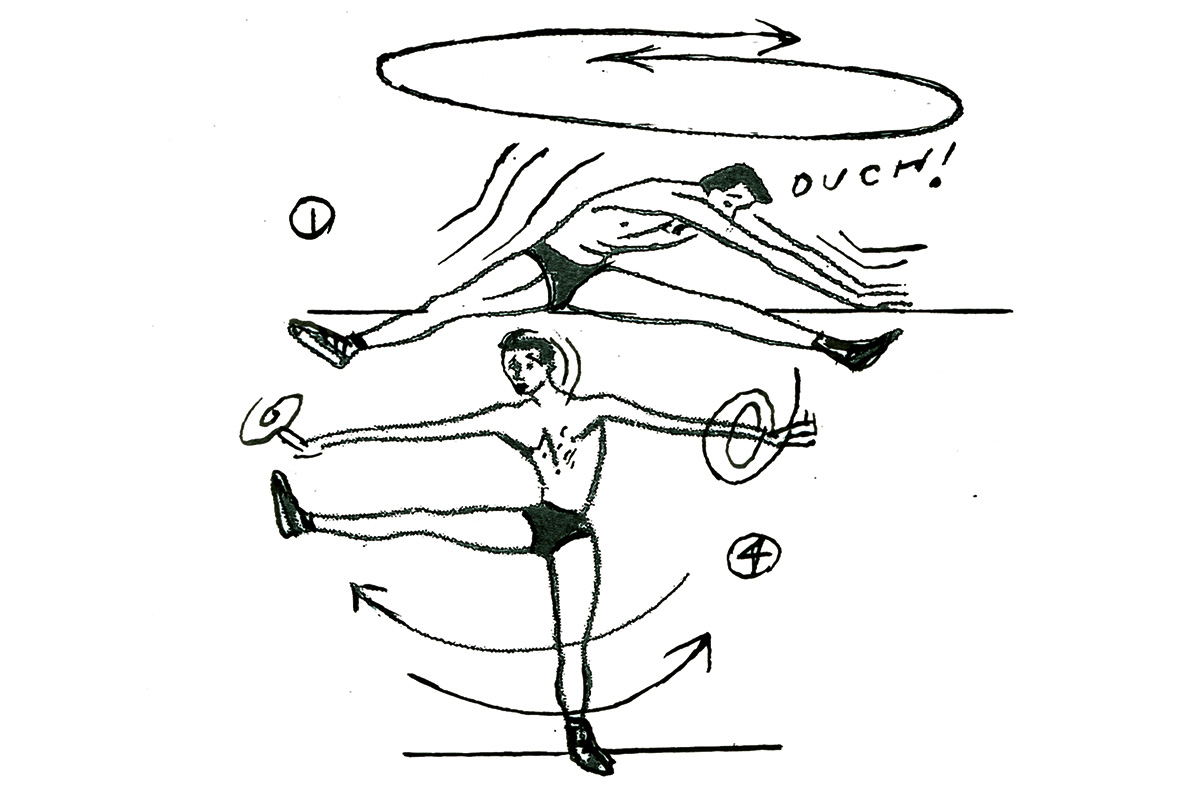

The description of the card includes a long passage about different rituals practiced by North American tribes. One ritual is called The Night of Fear. The seeker goes to a remote area, digs her own grave and lies in it. Then:

‘The opening of the grave is covered by a blanket. The sounds of the night and the nocturnal prowlers act as a catalyst that brings forth all of one’s greatest imagined fears so that they may be confronted. Since the person cannot see through the blanket, the sounds, combined with imagination, are his own worst enemy.’

This is exactly what the space between a biopsy and the results is — it’s my Night of Fear. My imagination has been running wild. Ridiculous, melodramatic scenarios run through my mind. I search Amazon for a pair of boxing gloves to hang over my bed. I’m going to fight, I think. I decide I’ll put on a brave face like Chadwick Boseman and won’t tell anyone while I continue to record my podcast and film my news show. The news shows I film…in my garage. Stunning and brave. Should I start working on a Spotify playlist for my memorial? Do I have the DNR set up for my social media? I push away images of my husband and my dog, Hope, at my bedside as I take my last breath. How could I leave them behind? I notice the purple of the jacarandas in bloom. Will this be the last year I see them?

I confess my morbid fever dreams to my therapist, who laughs and tells me they’re completely normal. According to my Sacred Path reading, ‘the fears created by an active imagination can lead to the retrieval of inner-courage or the total paralyzation of the senses’. Limbo leaves me feeling courageous and paralyzed simultaneously, but by the time this is published I’ll either have entered a waking nightmare or be the lucky schmuck who dodged a bullet. This bullet. But there’s another bullet coming. It’s just a matter of when — and for this I’m grateful for my Night of Fear. No matter what happens, it shined a light on what and who is truly important. It forced me to answer the question Kate didn’t get to: what would you do if you knew you had six months to live? More importantly: if you’re not doing it, why not?

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s July 2021 World edition.