Back in October 1983, the US invaded the tiny Caribbean island of Grenada. American medical students had been taken hostage by a Cuban-supported military junta, and Ronald Reagan ordered the US military to rescue the students, defeat Grenada’s small militia, depose the junta and put the island in the hands of its Governor-General. The intervention, Operation Urgent Fury, was an overwhelming victory for the United States – and the Reagan administration.

But the Grenada operation was a mess. As the story goes (albeit, through many iterations), during the intervention an Army commander needed support from offshore Navy assets. The soldier could see the ships but had no way to reach them. So he used a payphone and his credit card to call an American operator, who routed his call to the Pentagon, which put him in touch with officers at Fort Bragg, who contacted a Navy commander in the Caribbean, who patched him through to the captain of an offshore ship. For the Congress, it was the last straw. In 1986, they passed the Goldwater-Nichols Department of Defense Reorganization Act to ensure that what had happened in Grenada wouldn’t happen again.

Goldwater-Nichols dampened inter-service rivalry by taking the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) out of the chain-of-command (they recruit, train and equip, but do not command, US forces). It made promotion dependent on inter-service cooperation (‘jointness’), reinforced the influence of the joint staff (which answers to the JCS Chairman), improved the ability of the military to conduct combined operations, made the JCS Chairman the principal military adviser to the president – and enhanced the power of the military’s geographically unified combatant commands.

The consensus in the military is that Goldwater-Nichols has worked well, but senior officers acknowledge that has spawned some nasty, and disturbing, side effects. Not the least of them is the enormous growth in power of the commanders-in-chief (the ‘Cincs’) of the geographic, combatant commands. They are the equivalent of Rome’s imperial proconsuls, the true elbows-under-the-boards arbiters (the ‘Cinc-doms’) of American global power.

‘It used to be that if I had a question on American policy or just wanted to make a point, I’d call the US ambassador,’ a senior Turkish diplomat told me several months ago. ‘That’s no longer true. If I want to get something done, I ring up the head of the European Command. Why would I waste my time calling the ambassador?’ As it turns out, what’s true for the foreign ministry in Ankara is also true in for the State Department in Washington.

On Tuesday, Mike Pompeo flew to US Central Command headquarters in Tampa to confer on the burgeoning Iran crisis with Centcom’s Gen. Kenneth F. ‘Frank’ McKenzie and Army General Richard Clark, the head of the Special Operations Command. The secretary of state’s visit was highly unusual; it signaled the American military’s enormous clout, inadvertently confirmed by Pompeo’s groan-inducing statement to reporters that he and McKenzie discussed ‘the Centcom decision’ to move another thousand troops into the Middle East. In fact, as West Pointer Pompeo presumably knows — he graduated first in his class — while McKenzie had requested the reinforcements, the decision to add a thousand new troops wasn’t actually his decision, but the president’s.

Or perhaps Pompeo’s slip wasn’t a slip at all. As the secretary of state was meeting with Gens. McKenzie and Clark in Tampa, acting defense secretary Patrick Shanahan was being shown the door in Washington. Shanahan’s public self-immolation confirmed what everyone had been reporting for weeks: that US policy on Iran was being shaped not by Patrick Shanahan or Mike Pompeo, but by national security adviser John Bolton. In this sense, Pompeo’s visit to Tampa might have been unusual, but it was also predictable.

‘Pompeo can’t stand Bolton, absolutely can’t stand him,’ a former senior Pentagon officer who knows both says. ‘He needed to recapture the Iran policy, to show Bolton who’s in charge. So he trooped down to Tampa to confer with the military. I’m sure the message wasn’t lost on Bolton.’

In fact, Pompeo’s Tampa visit might well have misfired, as it inadvertently highlighted the growing influence not of Pompeo, but of Centcom’s McKenzie, as if he, not Pompeo or Trump, is the true arbiter of American power in the Middle East.

‘Pompeo’s visit came off as a kind of pilgrimage’, a senior Pentagon civilian official told me. ‘I mean, it used to be that when you wanted to confer with a military officer, you called them to Washington. That’s the way it should be, right? They come to you. You don’t go to them.’

A McKenzie admirer, and retired senior officer, agrees, if only in part: ‘You’re reading into this,’ he says. ‘Who cares who goes where. Frank is a hell of a Marine. He knows the military answers to civilians. Any suggestion that he’s pushing policy is nonsense. He has absolute respect for the chain-of-command and a finely tuned sense of who he serves.’

Which is another way of saying that McKenzie is viewed by his colleagues as one of the most politically astute officers to ever head up the US Central Command — a notable change from his sometimes controversial predecessor, Army Gen. Joseph Votel. Votel was outspoken and opinionated, and he bickered with Curtis Scaparrotti, the head of the US European Command. That won’t happen under McKenzie. A 30-plus year veteran of the Marine Corp, McKenzie served in combat deployments in Afghanistan and Iraq. But his most influential posting came in 2015, when he was assigned as the Director of Strategic Plans and Policy (the J-5), on the Joint Staff, which was followed by a stint as the Joint Staff’s director.

At the Pentagon, McKenzie worked to dampen the growing competition between combatant commanders, which was becoming a stand-in for the inter-service rivalries that had hobbled the military prior to the passage of Goldwater-Nichols. ‘Goldwater-Nichols certainly dampened inter-service rivalries and competition over resources,’ Lawrence J. Korb, a senior fellow at the Center for American Progress says, ‘but it didn’t do away with it. It’s never going to go away. There’s still competition for resources, and there always will be. But it’s not paralyzing. And, yes, there’s competition among the combatant commanders. But the military is aware of it, and taking steps to resolve it.’

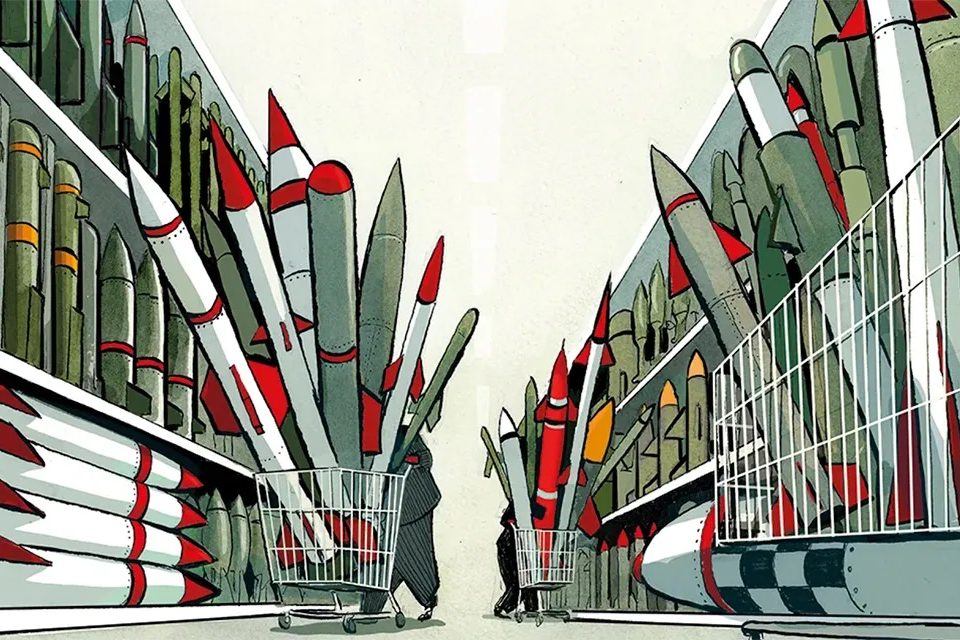

This competition for resources has spurred Pentagon worries that combatant commanders have been too parochial in their demands, sparking ugly competitions over who gets what. ‘It was always about the “preds” [predator drones] and who would get how many and when,’ a senior retired military officer notes. ‘The guy who makes that decision is the Director for Operations, the J-3. All that guy hears is “preds, preds, preds, where are my preds”?’

Eventually, Dunford got fed up. ‘Somewhere there’s a memo, signed by Dunford, that says “enough”. This was his hobby horse’ the senior Pentagon official with whom I spoke says. ‘The complaints were endless. No one was taking a look at the big picture.’

When McKenzie was named the joint staff’s J-5, he took Dunford’s crusade, becoming an outspoken proponent of ‘global integration’. McKenzie’s influence is still felt. During a recent public appearance at Washington’s Mitchell Institute of Aerospace Studies, Air Force Lieutenant-General David Allvin, the current director of strategic plans and policy, hammered home Dunford’s message, saying that the nation’s threats are ‘trans-regional’ and that combatant commanders need to ‘think outside of their AOR [their area of responsibility]’ and put their war plans in a ‘global context’.

Despite this why-can’t-we-all-get-along plea, it’s not clear everyone has gotten the message. When the Pentagon rolled out its 2018 National Defense Strategy, senior Centcom officers in Tampa were ‘damned near morose’, the former senior officer with whom I spoke says. ‘The whole paper was about peer competitors — Russia and China. The Middle East was an afterthought. It was well down the list of priorities. Which meant that Centcom would lose prestige and resources. No one in the military wants to scramble to be relevant.’

What Centcom officers were worried about is that they would take a back seat to the European and Pacific commands. In fact, there’s a clear, if unstated, pecking order among the commands, retired Col. Kevin Benson, a former director of the Army’s School of Advanced Military Studies, notes. ‘The three most important commands are in Europe, which is Eucom, the Pacific, which is Pacom and now, because of Iran, the Middle East – which is Centcom. Southcom, the Southern Command, is almost always last in priority.’

So while the threat of war with Iran might be bad news for the world, it turns out that it’s actually good news for the US Central Command — though no one in the military would describe it in precisely those terms.

‘Oh yeah, no question,’ the former senior officer with whom I spoke concludes. ‘The Iran thing puts the Middle East back on the military’s map. It means more weapons, funding, and all kinds of resources. Iran makes Centcom great again.’ Then, after a moment’s reflection, he adds a caveat: ‘You know, so long as there’s no shooting.’

Mark Perry is the author of 11 books on history and national security and a former adviser to PLO head Yasser Arafat.