In mid 2015, Macer Gifford, the City trader who went to Syria to fight Isis, got an unexpected phone call. He was in London for a break and busy doing media interviews as the unofficial spokesman for the Kurdish YPG militia. The caller, though, wasn’t just another hack after a quote. Instead, it was a lawyer whose client was on the ‘other side’. Tasnime Akunjee said he was working for the family of Shamima Begum, the teenager from Bethnal Green who had run away to join Isis.

‘He said they were looking at trying to get her out of Raqqa,’ remembers Gifford. ‘He asked if there was any way the YPG could pick her up, so that she could then be brought back to the UK.’

Was she keen to return, asked Gifford? No, said the lawyer, she was ‘young and a bit silly’ — but given a clear escape route, she might be persuaded. ‘At that point,’ Gifford says, ‘I told him that if she’s joined Isis, she’s made a bed for herself to lie in.’

Five years on, Begum is in a refugee camp in Syria, where she is appealing against the British government’s decision to strip her of her citizenship. Gifford, meanwhile, is bringing out a memoir about his time in Syria, which left him with little sympathy for the opposition — teenage girls included.

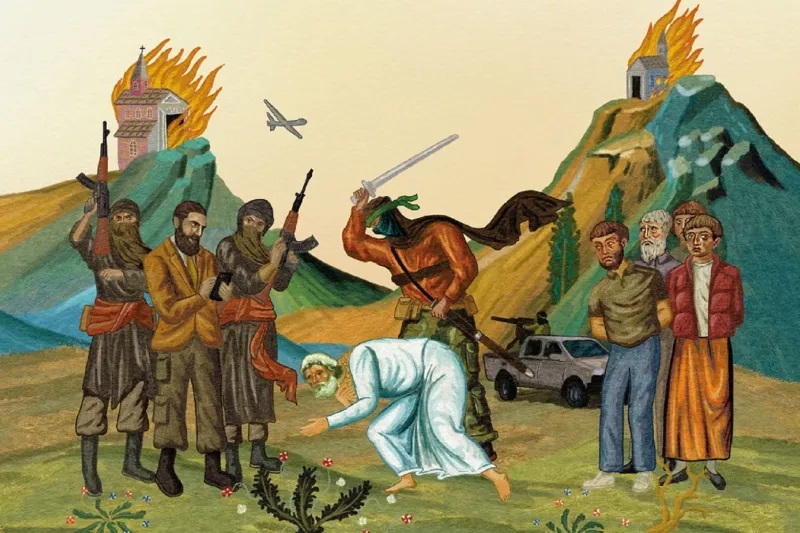

Fighting Evil is a modern-day version of George Orwell’s Homage to Catalonia, only with suicide bombers, drones and much dirtier combat. Some of the fiercest fighting is in Manbij, the town nicknamed ‘Little London’ because so many Britons lived there.

In his three years on the front line, 70 percent of Gifford’s original unit ended up dead. By rights, he should probably have been among them. Unlike many of the internationals, who were British and American ex-soldiers, his only previous military experience was a few weekends with the TA.

Today he’s back living in the UK. Even though he has always concealed his identity — Macer Gifford is a pseudonym — his high profile made him a target for Isis death threats. ‘People used to send me photos of dead international fighters with messages saying “You are next”,’ he says.

With the caliphate now vanquished, that threat has receded somewhat. But while he feels he’s now done his bit, he says Britain and the West should be doing much more to avert another crisis.

Begum’s case is just one of the challenges, he says. Like many, he’s skeptical of the narrative that she was a naive teenager, citing reports that she was part of the Hisbah (Islamic morality patrol) and stitched suicide vests. And if she does succeed in her appeal, he is not confident she will face any serious punishment on her return: ‘My fear is that she’ll get a slap on the wrist and then be free to enjoy the fruits of British society, while thousands of young Yazidi women who were raped by Isis are living with a life sentence.’

Of more concern, though, are the 12,000 Isis fighters — including 2,000 foreigners — his Kurdish colleagues hold in squalid makeshift jails in Kurdish-controlled territory in Syria. They include what Gifford calls the ‘SS’ of Isis, the diehards captured in the jihadists’ last stand in Baghuz last year. Britain, like many other European nations, has refused to repatriate them, and has done little to help the Kurds with prosecutions or improving the jails. The fighters are often crammed 100 to a cell, living in conditions that would horrify any human rights rapporteur. Which, Gifford points out, may be what will ultimately see them returned to the UK.

‘Because we’re not investing in any form of judicial process there, it will strengthen the case of those who argue for them to be allowed back here,’ says Gifford. ‘If the Kurds were helped to build proper prisons and courts, then at least they could serve their time where they committed their crime.’

Meanwhile, of the 400 British Isis volunteers thought to have already returned home, only around one in 10 has been prosecuted. Mr Akunjee, Begum’s lawyer, points out that not a single returnee is known to have caused trouble. Security officials claim nearly all 400 are on their radar, and that on return to the UK they are routinely questioned. In the absence of firm evidence against them, they can be put under various controls, including the counter-radicalization Desistance and Disengagement Programme. Yet the British government has disclosed little about the DDP’s effectiveness — beyond the fact that one of its alumni was Usman Khan, who killed two during a knife rampage at London Bridge in November.

‘These are people who may have raped and murdered, yet putting them in the judicial system is basically impossible because of the difficulty of pinning specific crimes on them,’ Gifford says. ‘It’s a kick in the teeth to the Kurds who gave their lives fighting these people.’

In his book, Gifford cuts a rather different figure to the swashbuckling thrill-seeker that some might expect. At university, he joined the Conservative party and became involved in human rights activism, working for Morgan Tsvangirai, the late Zimbabwean opposition leader. He volunteered to fight Isis because he saw it as fascism with an Islamic face, but says it was also a ‘Goldilocks’ decision — he was only 27, had no attachments and the Kurdish recruiters on Facebook made it easy to get there.

Most of the book is about going into battle, sometimes in armored tractors, sometimes doing World War One-style infantry charges. Chances were not helped by his Kurdish colleagues’ appetite for danger. At one point, one of the more level-headed commanders was forced to resign for being too timid in battle, based largely on the fact his unit hadn’t suffered enough casualties.

[special_offer]

To begin with, Gifford was convinced he was going to die; by the end, he was so used to combat he feared he was getting careless. ‘There’s a danger you become addicted to war,’ he says. ‘When you lose your fear, that’s when you start doing stupid things.’

Since returning from Syria, he’s completed a masters in security and peace-building, and is now planning to write a novel. ‘If I meet someone in the pub these days and they ask what I do for a living, I just say I’m a human rights activist,’ he says.

His nom de guerre, meanwhile, lives on only in interviews to promote the anti-Isis cause. And once it becomes clear that Isis is finally dead and buried, Macer Gifford will be able to RIP too.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the US edition here.